Unframed is taking a look behind the scenes to profile the dedicated and creative people who make LACMA special. We sat down with curator and head of the Latin American Art department Ilona Katzew to talk about her upcoming exhibition Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici, how paintings have their own histories, discovering a viceroy under layers of pink paint, and skipping school on a clandestine bike.

Since arriving at LACMA in 2000 as our first curator of Latin American art, you have bolstered the collection with numerous acquisitions and organized major exhibitions of Latin American art. You’re currently working on a new show, which opens in June at Fomento Cultural Banamex in Mexico City (our co-organizing institution), before coming to LACMA in November and ending its tour at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Can you tell us a little bit about the latest exhibition?

The exhibition I’m working on is Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici, which is devoted to 18th-century Mexican (or New Spanish) painting, a period that I find particularly rich artistically and historically, but which is not so well known. In many ways, organizing this exhibition is coming full circle for me, as I’ve been looking at and thinking about this material over the last 20 years.

Why do you think this area has not received its due attention?

Spanish colonial art, especially painting, has often been compared to European art in qualitative terms. For a long time there was this notion that Mexican painting was essentially a byproduct of European artistic traditions. In addition, the generalized criticism of the Baroque and Rococo coming from Europe in the 19th century also impacted the perception of 18th-century Mexican art. The 18th century was often described as a period of “decadence,” as overly sweet and somewhat languid, especially when compared to the 17th century, a period that has received more scholarly attention.

In the past 10 to 15 years, however, there has been a significant shift in the appreciation of the field, and more and more scholars have taken an interest in the material. But the wealth of images is just extraordinary, and truthfully we’re only beginning to make more serious inroads.

It must be exciting to look at and understand this era in a different way.

Yes, this has been a highly rewarding journey. Of course, scholars in Mexico have done really wonderful work in this area, and I have huge admiration for my colleagues there: many are not only out in the field studying this material but also making concerted efforts to restore and preserve it, which is extremely important. But it’s true that internationally the field hasn’t received the attention it deserves and that it’s not always seen as part of global art history. One of our hopes in organizing this exhibition is to open up a vista to the extraordinary legacy of this period and get people intrigued and excited, and also to understand the deeper connections of 18th-century Mexican art with larger transatlantic trends; that is, how it was part of the larger internationalization of art.

What was the genesis of this exhibition?

It’s an idea that I had been contemplating since 2004 when I published my book on casta painting, and realized how challenging it was to find information about the painters or even get a sense of their body of work. A few years later I was invited to write a book chapter on 18th-century Mexican painting and was just aghast at the wealth of material and how little, proportionally, I was able to get into the chapter. I thought, “Why not explode the theme into a bigger exhibition and book?” This was around 2010. I then called on three friends and colleagues of Mexico and Spain who are leading voices in the field—Jaime Cuadriello, Paula Mues Orts, and Luisa Elena Alcalá—and asked if they’d be interested in joining forces.

Over the past six years we’ve traveled tirelessly all over Mexico to see works tucked away in churches, private collections, or even stored away in closets. It’s been amazing to see so many extraordinary paintings hidden in buildings that were once manifestly grand, many of which have now been divided into lots or are in a dire state of ill repair. We also visited collections in Spain and other cities across Europe, where many New Spanish paintings were shipped in their own day. The real challenge was: how to do justice to such a rich field through such a comparatively small selection. We had collected well over 2,000 photos of paintings in our trips! From the outset, we knew that some works would be virtually impossible to move from their original context, but at times we truly struggled with having to select some works over others.

How did you find these works, if some were tucked away in closets and monasteries?

Among the four of us we have some 80 years of combined experience in the field, and each of us has access to different resources. Plus we were aided by many friends and colleagues along the way who opened doors for us; it truly took a village.

You were sole curator of shows like Contested Visions in the Spanish Colonial World (2011–12), your last major historical exhibition here at LACMA that bridged pre-Hispanic and Spanish colonial art, and you have three co-curators for Pinxit Mexici. What was this collaborative experience like for you?

The nice thing about the collaboration is that we really tried to listen and learn from one another, and even changed our minds about things as we saw and studied more. But in the main we are all profoundly committed and passionate about the material, and at some point we just realized that what we were doing superseded our individual interests and tastes. Our goal was to make more resources available and elicit greater interest in the field.

I understand you and your co-curators made some surprising discoveries. Could you share any stories?

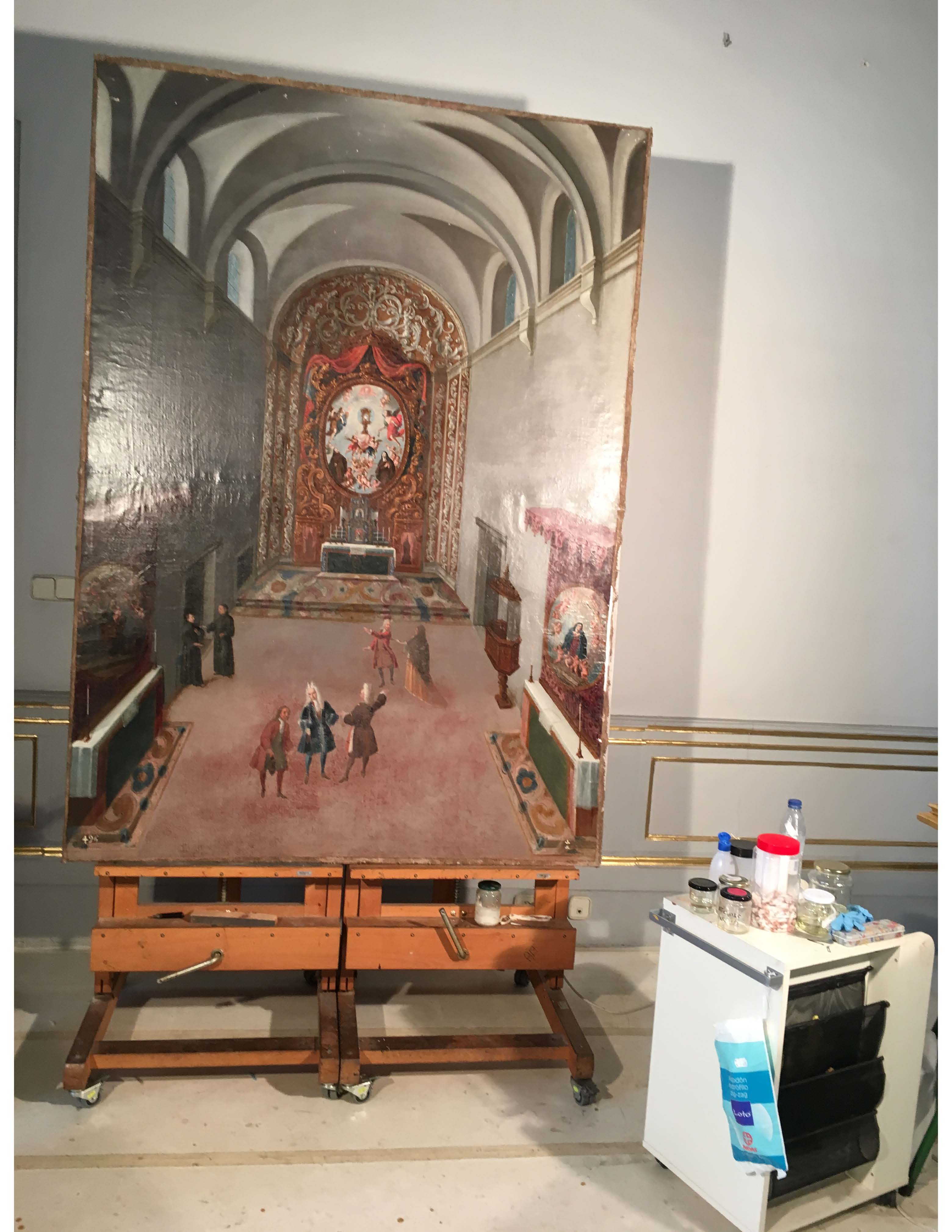

There is one painting, Interior of the Church of Corpus Christi (above), which will be displayed at the entrance of the show. It depicts the interior of a church in Mexico City called Corpus Christi. I wrote about it for the catalogue, which gave me a chance to plunge deep into its history. I had seen the painting in person at the Palacio Real de Madrid, and kept thinking that it looked odd, with its large empty space in the foreground. In addition, the floor was painted in an overwhelming pinkish pastel tonality. I thought, this just does not look right, so I asked Joe Fronek, our head of paintings conservation with whom I often travel to view paintings, if he would be willing to take a closer look at the picture on our next trip to Madrid.

When we saw the picture again, I noticed a faint silhouette in the middle ground. I kept telling Joe, “I think there’s a figure there that was covered up. I wonder if it could be the viceroy who founded the convent.” Joe agreed that something was peculiar, and recommended that we ask the Palacio Real to X-ray the painting. After a few months, the Palacio Real graciously supplied the X-radiograph, where we could now see a whole scene with multiple figures! It was one of those incredibly exciting moments. My interpretation of the painting completely changed because of this discovery. And the experience reinforced just how important conservation is when we look at and interpret paintings.

What did the Palacio Real do with that information?

All along we had planned to restore the painting for the exhibition and prepare it for travel. But after commissioning the X-radiograph the conservators at the Palacio Real realized that it was a relatively simple matter to remove some of the overpaint and recover part of the scene that had been obliterated. Art historically, however, the fact that the picture was painted over (we don’t know exactly when) is significant, so they took this into account and addressed the process in a very sensitive manner—for example, leaving the figures standing near the door that were transformed from halberdiers of the viceroy’s palace guard to Franciscan friars.

Why were they changed to look like Franciscan monks?

Whoever had the painting covered—I want to believe it was the viceroy himself or someone close to him—wanted to show that the church was empty. My take is that the viceroy wanted to prove that the building was completed but vacant, still awaiting royal confirmation. The Franciscans are shown as custodians of the empty building. Being the first convent for indigenous women, the establishment of Corpus Christi was a bit of a contentious matter in its own day, with many people opposing it. The viceroy who commissioned and paid for the building was using painting to advocate his cause.

How did you know something was covered up? What tipped you off?

Sometimes, when you’ve seen so many paintings you end up developing a sort of sixth sense. I don’t know how else to explain it. It just didn’t seem right.

What are some other takeaways from the restoration process?

I’m a big proponent of learning more about the material and technical aspects of pictures because of how much information it reveals, often affecting our reading of the works. Paintings have their own histories, and the opportunity to work so closely with conservators has been highly rewarding. The entire curatorial team is very attuned to similar issues of restoration and preservation. In fact, one of our goals in organizing the exhibition was to call attention to the ongoing need to restore and preserve works across Mexico, and to the materials and processes employed by New Spanish artists. Paula Mues Orts deals with this subject at length in her essay for the catalogue.

Were there any paintings you couldn’t remove from the site that you really wished you could have?

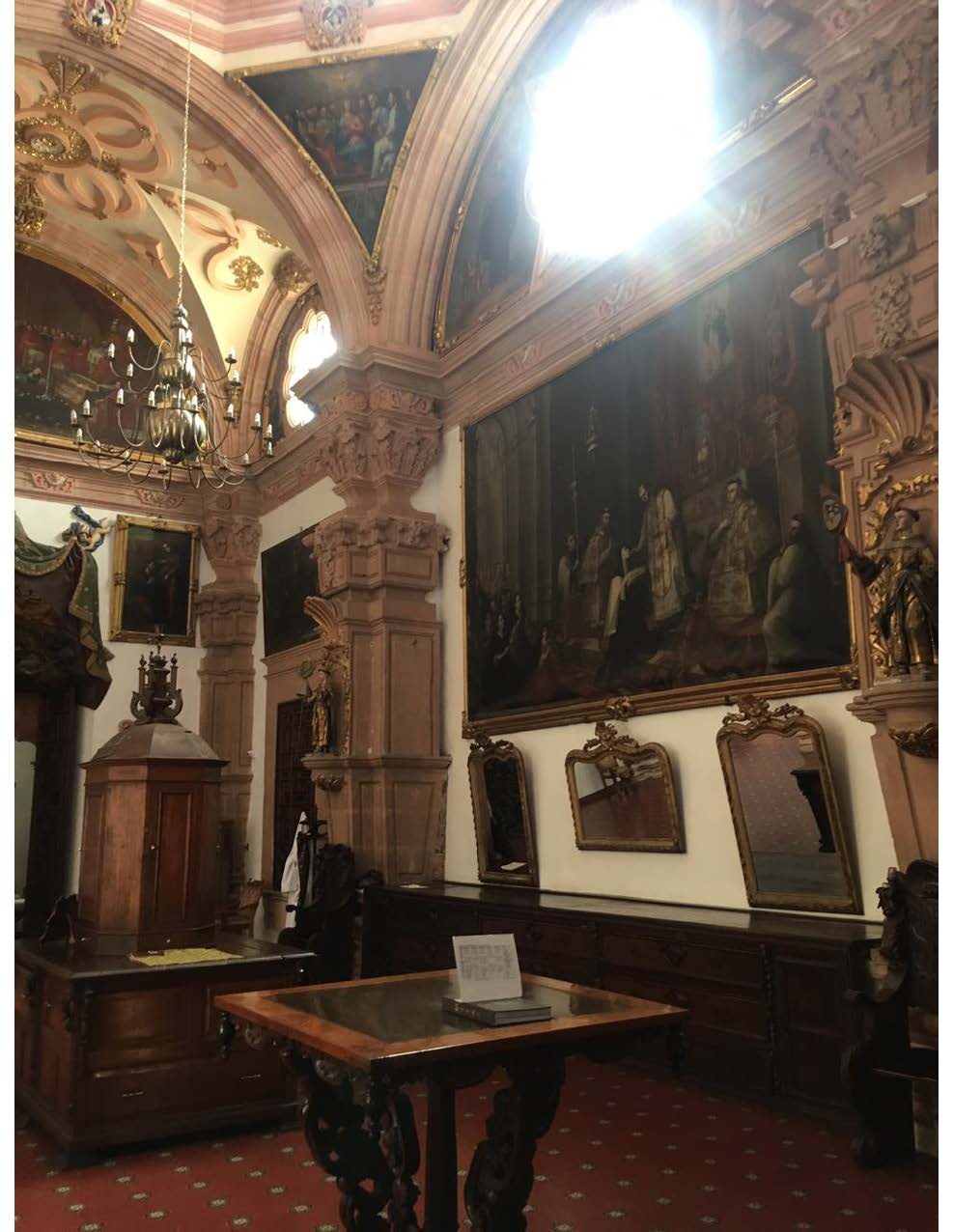

Yes, many! But there is one case that stands out: an amazing painting by Antonio de Torres, which is in the Franciscan church in San Luis Potosí, in north-central Mexico. It’s been there since it was commissioned in 1720. It’s a touchstone of the period, a grand and seminal painting, which is not easily accessible. We wanted desperately to include it and restore it for the exhibition. Then, we realized that not only would it not fit in the plane but that we didn’t have a wall tall enough to accommodate it. We tried and tried, and when we finally had to let go, it was a low moment for the entire curatorial team. Fortunately, Jaime Cuadriello got to write about the painting for the catalogue.

Is this still a working church?

Yes, and a beautiful one with one of the most impressive collections of paintings still in situ. Quite a few works are coming from churches across Mexico.

It’s surprising, at least to me, that masterpieces like these remain in churches for which they were originally commissioned.

Many of these churches are still active and the paintings are part of their day-to-day life. As art historians, we tend to look at them as works of art, but they hold different meanings for different people in those communities.

Let’s talk about LACMA’s collection of Latin American art. We have been steadily acquiring important works of Spanish Colonial art over the last decade, and what’s really interesting about your department is that you’re collecting 18th-century works alongside modern and contemporary works.

One of my main goals in building LACMA’s collection of Latin American art has been to create, if you will, some sort of “historical infrastructure.” When I arrived there were no Spanish colonial works in the collection. We only had a 16th-century Mexican chalice that came from the William Randolph Hearst collection. I’m a firm believer in the importance of history and understanding and appreciating the past to create links with the present. Nothing exists in a vacuum and a museum such as LACMA has the responsibility to create these bridges by broadening its collections geographically and temporally.

Plus, moving between the past and the present is something that suits who I am and how I think and perceive the world. I actually also trained as modernist and am just as excited when I acquire works by modern artists working in Latin America, such as Julio Le Parc and Gyula Kosice, whom I had the great opportunity to meet in person. Works by both artists are now on display in the galleries.

Going back to the very beginning: what drew you to Latin American art?

I grew up in Mexico City. I would skip school to go to churches and visit museums. I thought they were pretty awesome. I had a clandestine orange bike that I would hop on. My mom only learned about it two years ago.

What was her reaction?

She was horrified, of course! I just thought the artworks were so amazing. I didn’t have much context to understand what I was seeing but visually they had such a strong presence. I knew early on that I wanted to learn more about them.

Did you have favorite churches you frequented?

I loved the Cathedral, and I still do to this day. I really liked the Franciscan church now on Avenida Madero. The original complex, which was enormous, was divided and turned into commercial buildings, but you can still get a sense of how grand it once was.

And were you similarly influenced by museums?

I always gravitated to museums. They were a place of solace for me, where you could go to commingle with the “higher spirits.” I remember seeing shows on Picasso at the Museo Tamayo and an exquisite exhibition of Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings at the Palacio de Bellas Artes that had a huge impact on me. I must have braved the long lines about five times to look at those drawings over and over again. I always thought that museums were this unique space where you could find a sense of peace and beauty, and “see” the voices of others. Museums are like temples for me, in a way, but also places where you can learn.

Has that sense changed since you began working in museums?

I’ve become more selective about what I see. I don’t enjoy being overwhelmed by too many things concurrently; I’d rather spend half an hour with one artwork or small group of works. We’re in such a funny time right now. We’re bombarded by images through the media, and I think that our capacity to absorb more deeply, take the time to truly contemplate a single work of art is sometimes compromised. I try to make up for the pressure to take in as much as possible—and so quickly—by spending more time with fewer objects. If you give things time and truly “look with all your senses,” it’s extraordinary how much you can discover in the process.

Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici opens at Fomento Cultural Banamex, Mexico City, on June 29. The show will be open at LACMA on November 19, 2017 as part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, and subsequently travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in March 2018. In the meantime, you can view our recently installed Antonio de Torres’s The Elevation of the Cross in the Latin American art galleries.