An icon of West Coast Pop, Ed Ruscha is known for his works in a wide variety of media; his images are typically text-based and/or depict the deadpan yet nonetheless expressive landscapes of his adoptive state of California. He frequently portrays gas stations, parking lots, swimming pools, the Hollywood sign, and many other aspects of Los Angeles and its surroundings. LACMA owns almost 500 works by Ruscha, including the celebrated 1962 painting Actual Size.

For Artists on Art, LACMA’s online video series featuring contemporary artists speaking on objects of their choice from our permanent collection, Ruscha selected Marcel Duchamp’s With Hidden Noise (conceived 1916, fabricated 1964).

Back when you were a young artist in L.A., shortly after you went to the Chouinard Art Institute here, you saw Marcel Duchamp’s 1963 retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum.

I did, and I was fortunate enough to meet Mr. Duchamp. He was sort of the opposite of what we expected an artist to be, which was in paint pants and scruffy and all that. He was in Sunday best. He had a suit and tie. He smoked his cigar as his show was being installed. And I was fortunate enough to meet him and go to his opening, and it was quite something. It created a stir among artists—many artists showed up, and so it was a very good thing. The story that went along with it was good, too, because he had never had a retrospective exhibition of his work. He had managed to upset things by saying he wasn’t going to make art anymore. He wanted to play chess for the rest of his life.

That same year as the Duchamp retrospective in Pasadena, you made your iconic painting Noise—just that word standing on its own, in yellow, on a blue background. Is your work a response to Duchamp’s?

I’m not sure . . . I have a lot of backdoor influences, and things that I’m unaware of in my work that could actually become true after a while. I don’t recognize it at the time I make them. So whether or not his words “hidden noise” had anything to do with my painting of the word “noise,” I can’t say.

But you’d name Duchamp as an influence on your work?

I saw him as a person introducing simplicity to the discussion. I’m really influenced by everything, even things I hate. Even things that I have no respect for, I’m influenced by. But his art, the objects he used and all that, were different enough and simple enough. He brought these unlike materials together and sometimes they clashed, sometimes they didn’t. They always carried some kind of riddle. He offered something else to the world, and it was a little strange and unsettling, but provocative. So, I liked his work a lot. I can’t claim to be a disciple of Duchamp, but he did play an important part in my observation of the art world and art. We share that for certain.

He is famous for conceptual art, often based in word play. You’ve painted words since the 1960s.

I think his titling, the titles he put on his work, are as provocative as the works themselves—his little double-entendre things. My own work generally comes about by not planning too much, and not assigning definitions I might put into a picture. It’s more spontaneous, but it is pre-planned, and I don’t always go for the gut when it comes to trying to make something mysterious or non-mysterious.

You are known for your two-dimensional work. Why, for Artists on Art, did you choose to speak on a sculpture by Duchamp?

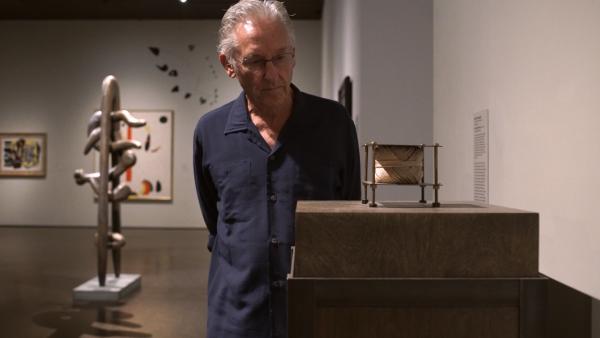

I never really got into sculpture much, but I do consider some things I make sculpture. Books are an important part of my work and they rise up off the table by so many inches. I would call that sculpture. [Leans in to look closely at With Hidden Noise] I like these odd challenges between the ball of twine there, which is sort of an innocent object in itself. And then it’s contained—forcibly contained—by this oppressive thing, you know, this metallic thing that’s holding this together. It just asks to be talked about. . . . If I were to pick it up? No? You wouldn’t advise that, huh? [Pauses] There’s actually a mirror there, too. . . . I was thinking it might put a pox on anyone who talks about it too much.

Marcel Duchamp’s With Hidden Noise is on view in the Ahmanson Building, Level 2. The conversation was edited and condensed for clarity.