Unframed is taking a look behind the scenes to profile the dedicated, creative people who make LACMA special. We sat down with LACMA’s new assistant curator for film, Adam Piron, to talk about rethinking what a classic is and highlighting different perspectives.

You’re brand new to LACMA. Welcome.

Thank you, it’s been about three weeks.

And you came from Sundance. What did you do there?

I started at Sundance as an intern in their Native American and Indigenous Film Program. I was an intern at the same time as Dilcia Barrera, the previous film curator at LACMA. We had a similar trajectory at Sundance and became good friends. In 2013 I joined the short film programming team. In 2014 I became a manager of the Native American and Indigenous Film Program. I did a lot of artist support, working with Native artists—Native American, both North and South American, Pacific Islander, Native Hawaiian, Alaska Native, and from Australia, New Zealand, Oceania, some parts of Europe. I helped filmmakers tell their own stories and get their films in front of new audiences, whether through Sundance or other festivals and screenings.

What made you interested in coming to LACMA?

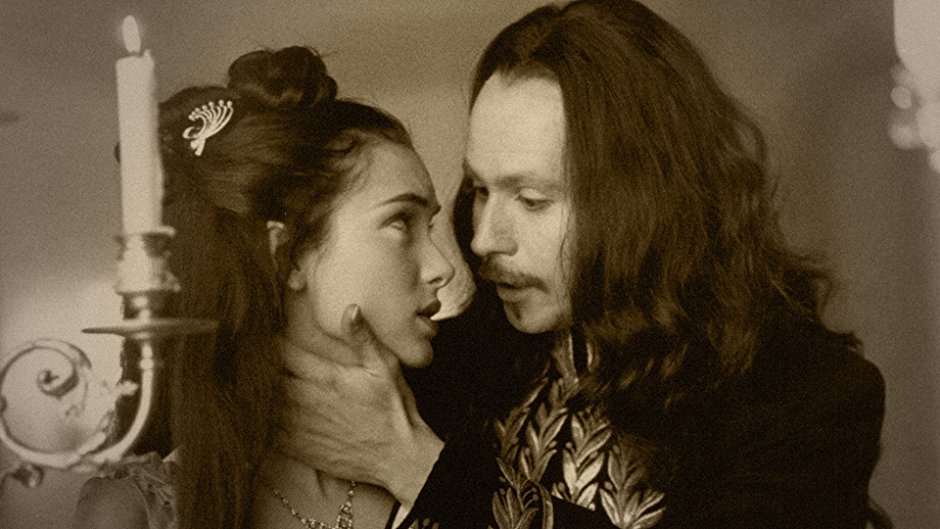

I liked the idea of a dedicated film program within a museum. Tuesday Matinees’ focus on classic films intrigued me. There’s a dedicated member base and audience that come to these screenings. It’s an interesting challenge: how can I put my own spin on some of the programming, whether through themes or highlighting different filmmakers or artists? I’m interested in reframing and reevaluating what’s considered a “classic” film and pushing the boundaries. Before she left, Dilcia programmed Cher films for September and horror films with Winona Ryder for October. In November, we’re also showing films connected to Howard Hughes. All of those films are seen within the breadth of how we now define what a classic film is.

What would be on your list of top-five classic films?

In no particular order: The Wizard of Oz (1939)—when you think about it, it’s a road movie with a robot and a scarecrow and an emotionally unstable lion. It’s a weird film, in the best way. Last Year at Marienbad (1961)—we actually have a print of it here. Kiss Me Deadly (1955) by Robert Aldrich, which is an essential noir and L.A. film. The Color of Pomegranates (1969) by Sergei Parajanov. Chungking Express (1994) by Wong Kar-wai.

What do you hope to do for Film at LACMA?

I want to present a blended mix of classics and offer different perspectives, expanding the definition of a classic films and their genres. I want to engage our current audience, as well as bring in new audiences, and create a space for them to celebrate and share their love for cinema in all its forms. My general strategy for Tuesday Matinees is to show films that will get people to call in sick or take a really long lunch break.

What do you have planned for December?

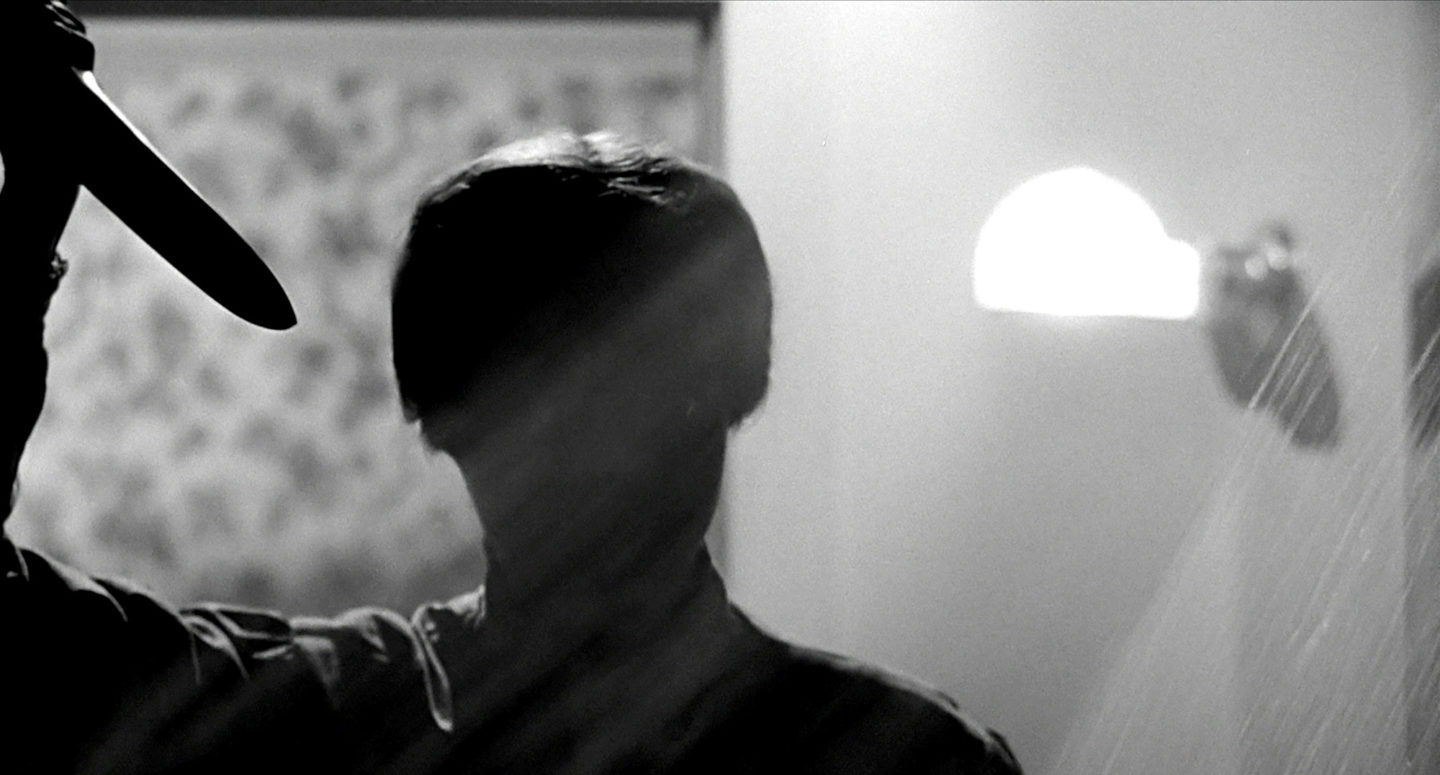

I’m doing a program centered around Christmas films that aren’t really about Christmas. One is Blast of Silence (1961), a film noir about a hitman who comes back to New York during the holidays and gets a conscience; he has a crisis about what he’s doing. Another is Psycho (1960).

Psycho as a Christmas film?

I think it is. The story opens on December 11 and unfolds over roughly nine days, and I’ll actually be screening it on December 11. I’d like to close the month with Eyes Wide Shut (1999), which is also a Christmas film even if people don’t necessarily think about it that way.

Tell us about some other upcoming screenings.

At the end of November we’ll be doing a screening and book signing with Karina Longworth, who runs the podcast You Must Remember This. We also have a lot of premieres, newer films, and episodic work with artist discussions, usually with a director or with talent. We just screened Kusama—Infinity (2018) with director Heather Lenz. Coming up we have Smallfoot (2018), A Million Little Things, a pilot from ABC, and The Old Man & the Gun (2018), an upcoming David Lowery film with Robert Redford. We’re going to screen a double feature of films that inspired the director in making The Old Man & the Gun—the original RoboCop (1987) and Two-Lane Blacktop (1971). This part of LACMA’s film program speaks to the museum being a gathering place for the community, engaging with artists and art. And many of the screenings are free.

Is there a difference when programming for an encyclopedic museum rather than a place like Sundance, where film is the focus?

At Sundance, the focus is on discovering and supporting voices of independent artists. Here, the challenge is a little different. How do you present something that’s familiar in some sense but encourage people to discover it? You can do this through experiencing these stories in a theatrical setting; you want a theme, a discussion, a conversation about these films, and you can also see it on 35mm. Because LACMA’s encyclopedic, there is a lot of material to draw from. It’s similar to the exhibitions we have here: how do you present the art from a different angle while still making it accessible?

Speaking of exhibitions, have you had a chance to check out the galleries? Have you been drawn to anything in particular?

I’ve been wanting to check out Decoding Mimbres Painting: Ancient Ceramics of the American Southwest. I’m Native American and I grew up in the Southwest, but I haven’t thought about the artwork in that way.

Before we let you go, can you tell us about your creative outlet?

I’ve been getting back into making films—smaller, experimental work. I’m really into experimental filmmakers like Sky Hopinka, Adam and Zack Khalil, Caroline Monnet—they’re filmmakers whose work I became familiar with through my work in Sundance’s Native Program. There are a good number of Indigenous filmmakers pushing the idea of what it means for Native Americans to be in film, what it means to make a film from a distinctively Native perspective. As opposed to trying to fit an experience into a rigid three-act structure, which is a very European idea of a story. I’m interested in experiences that are unique to a very specific culture, tribe, or personal perspective.

I also have an idea for a future film program about Native people as just everyday people, within the context of the films that they’re in. From the beginning of film’s history, it seems that whenever you see Native people on screen you have to bring up their culture, a reservation, or this country’s mistreatment of Native peoples. Very rarely do you see Indigenous characters who may not even say what their background is and just are who they are. For some reason that’s weird to a lot of people. But in your everyday life it isn’t something that comes up all the time. So I have a good selection of films I’d like to program; hopefully addressing and creating a conversation about why those images of Native people are so few and far between. We’ll see what happens.