Analia Saban’s work uses medium as the subject and experiments with traditional art categorization. Her paintings become sculptural and her sculptures are flattened. Her drawings are three-dimensional and materials typically associated with one medium are expanded into new forms. Saban uses technology and technique to dissect structure and explore the process of art-making. Originally from Argentina, Saban is currently based in Los Angeles.

For Artists on Art—LACMA’s video and public program series featuring contemporary artists discussing objects of their choice from the museum’s permanent collection—Saban selected artwork by Sol LeWitt and Frederick Hammersley from LACMA's Prints & Drawings collection.

Saban explains why she selected this artwork and how it relates to her own art practice.

“One of the most important moments for Sol LeWitt was in 1968 when he did his first wall drawing. It was a drawing that had vertical lines, diagonal lines, and horizontal lines, and by combining those lines LeWitt developed a set of rules. He did the first wall drawing himself but then he asked other people to do the drawings from that moment on. In a way it was kind of like developing a program or software. He would give this set of rules to somebody else and then that person, by making the drawing, would “print” it on the wall.

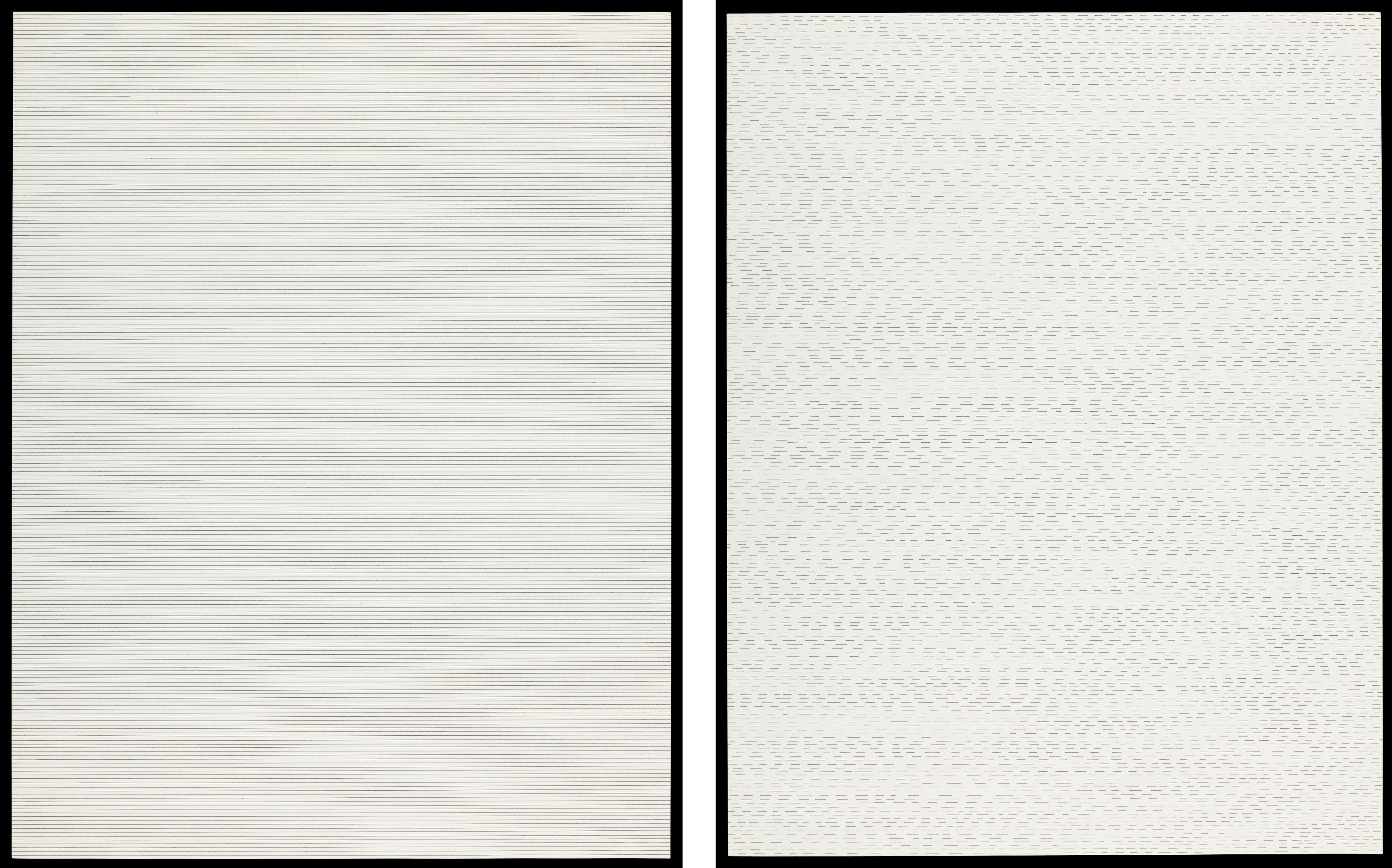

“Following that tradition in 1973 he made this portfolio which is a set of seven etchings. It's called Three Kinds of Lines & All Their Combinations. The first print is called Straight Lines, the next is Not-straight Lines, then Broken Lines, then Alternate Straight & Not-straight Lines, etcetera.

“Once you see the set of straight lines, even though it's very simple, you realize the complexity of one line, and even more complexity of many straight lines together. You see where the line begins, where the line ends, whether he used the ruler. And then you see that the straight lines are actually not so straight because it's not computer-based it's actually made by hand. I think it teaches the viewer what a straight line is and you realize very quickly that a straight line is quite complex. Even more complex is a not-straight line. There you see a much more human line. You see the rhythm of the hand, and how it can go up and down, and you see his faults. The line is much more related to gesture.

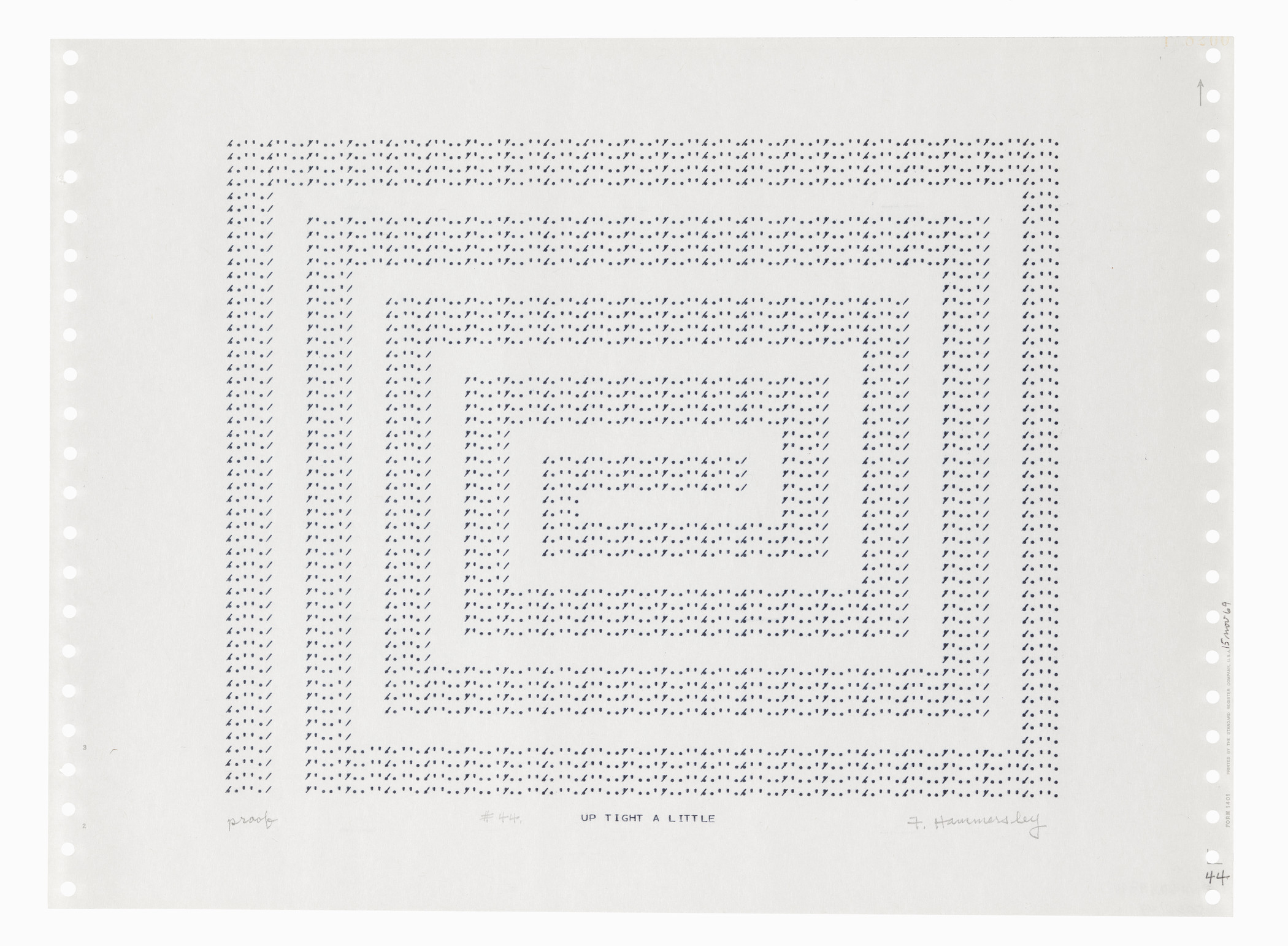

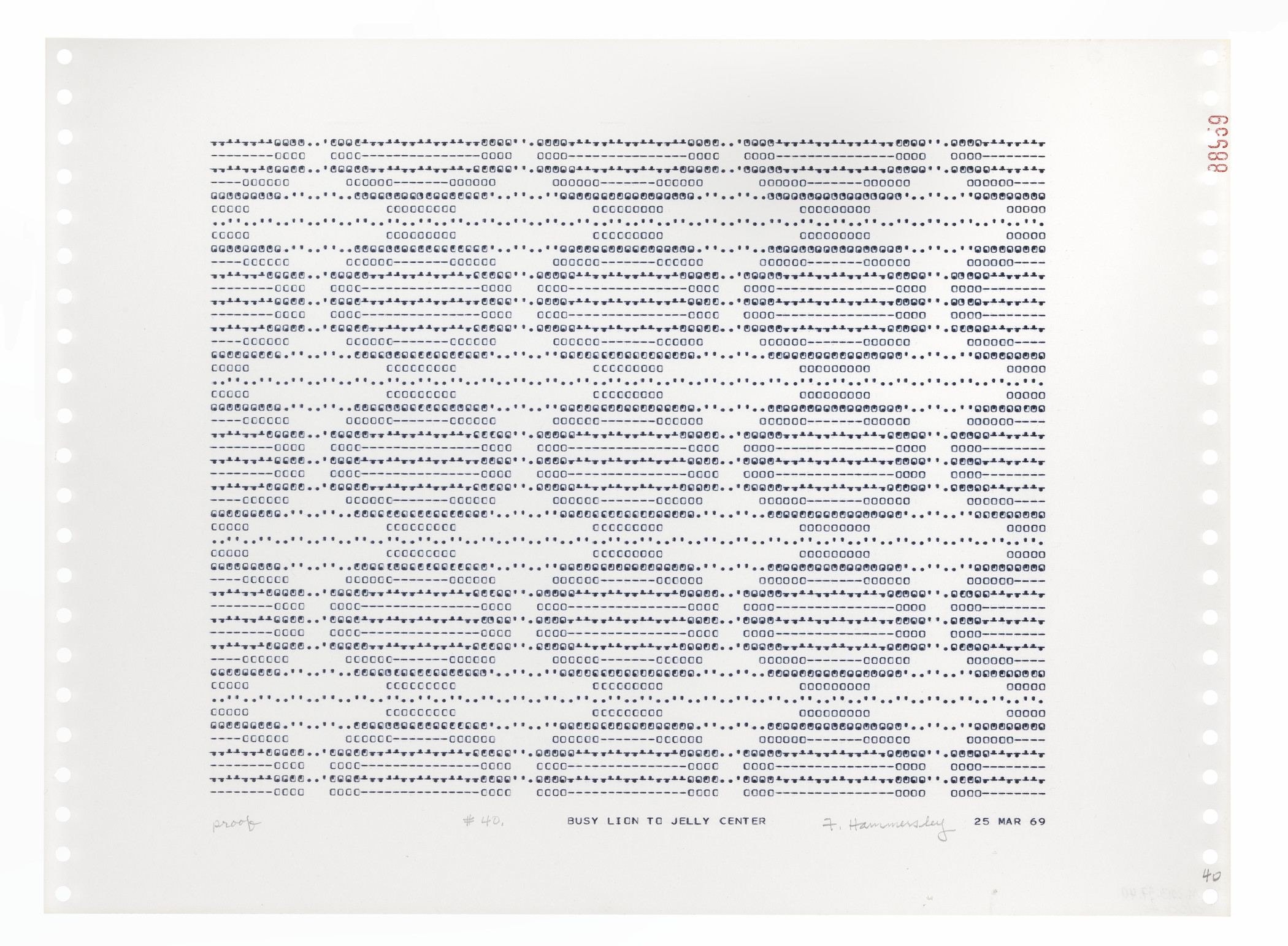

“I thought it'd be interesting to have a dialogue between the Sol LeWitt portfolio and this untitled portfolio by Frederick Hammersley that he produced in 1969 at the University of New Mexico. Hammersley talks about this moment in his life where he was painting a lot and he got a little bit tired or burnt out and went to teach at the University of New Mexico. He took a class called Art One, which was one of the first computer graphics classes probably in the history of computers.

“The way Hammersley made these drawings was by programming a punch card. The punch card would be fed into a printing program and then the printing program would print the actual drawing. They are drawings with very limited elements. They were each made in a grid of 105 characters by 50 characters. He's using only letters, punctuation marks, and numbers. That's all he has. Even though he's using a very limited set of characters the lines become very complex. At the beginning of the portfolio there are very simple compositions and toward the end there are very complex compositions. I think it was difficult for him to make the drawings using a computer without a monitor. This is something I admire as an artist because there is a whole process of trial and error.

“I chose these works because I have a secret passion for the history of computer drawings and for the history of conceptual art which is basically what came before me. I'm always interested in what makes art “art,” and I think a lot of it has to do with time and space. If you were to look at these drawings out of context you would just see a set of dots. But if you were to look at them as drawings made in 1969 you would see how this set of dots was basically changing the way a line was defined. A line could be defined by a set of computer characters. This wasn't the case until then. After this we developed computer graphics more and more until we have Photoshop, and so on.

“I'm always interested in how technology and different processes that are developed at a particular time can inform the art that we make. This is something that I always research and use in my own practice. In my own studio, I have very high-end technology, meaning I have computers, and I have a very precise laser cutter that's all computer-based. I also have very traditional techniques, like a whole weaving section, and a darkroom for photography. I think it's interesting that those tools help you define what art can be at a particular time.”

The conversation was edited and condensed for clarity. View more Artists on Art interviews on LACMA’s YouTube Channel.