*Throughout this blog post the terms Indigenous and Native are used interchangeably.

LACMA’s Mark and Carolyn Blackburn Collection of Photography encompasses over 9,700 rare Oceanic objects. The extensive collection includes historic photographs spanning from 1840 to 2016, including many rare images of Hawaiian royalty and historically significant locations. In order to fully catalog and research the Blackburn Collection, LACMA was awarded a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) in 2017. With this grant, LACMA teams in Registration, Collections Management, and Collection Information & Digital Assets (CIDA) have been able to catalog, process, rehouse, and digitize over 9,700 photographs.

Although the Collection spans well over 10 Pacific Island nations, we decided to start our research with the over 1,500 (and counting) Hawaiʻi photos since our consultant Joy Holland’s expertise is in working with Hawaiʻi and Pacific collections. So far, some of the themes I have come across are early European contact, the Sandwich Islands, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, Hawaiian royalty, and the Big Five corporations. “The Big Five” as they are more commonly known, were a group of five politically powerful sugarcane corporations in the Territory of Hawaiʻi whose owners supported the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. These corporations were Castle & Cooke, Alexander & Baldwin, C. Brewer & Co., American Factors, and Theo H. Davies & Co. They are important because they represent a pivotal point in Hawaii’s history—the transition from a sovereign Kingdom to a colonial territory. Other themes I have observed are the Territory of Hawaiʻi (1900–59), World War II and militarization, post World War II, statehood, the plantation era, immigration to Hawaiʻi, hula, Hawaiian and European architecture, Hollywood, and surfing. The following photographs are some highlights that I’ve chosen from the Collection that represent different yet important aspects of Hawaiian history.

Following Charles Lindbergh’s successful solo transatlantic flight in 1927, James Dole (1877–1958) of the Dole Pineapple Co. sponsored a 2,439 mile air race across the Pacific Ocean from Oakland, California to Honolulu, Hawaiʻi (American Oil & Gas Historical Society). The first pilot to land in Honolulu would win the first prize of $25,000 (about $370,000 today). Arthur Goebel Jr., a Hollywood stunt pilot, joined the air race along with seven other pilots. Goebel was sponsored by Frank Phillips, president of the Phillips Petroleum Company in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Phillips Petroleum Co. was well known for it’s aviation fuel research after providing high gravity gasoline for airplanes after World War I (American Oil & Gas Historical Society). In addition to funding Goebel with $4,500 to purchase a Travel Air 5000 monoplane, Phillips Petroleum Co. also supplied Goebel with its new formula of aviation fuel for the flight. In honor of Frank Phillips, the monoplane was named “Woolaroc'' after Phillips’s family ranch in Bartlesville. The photo above is a snapshot of Phillips and Goebel posing next to the Woolaroc moments before Goebel joined the race.

On August 16, 1927, along with the other competitors, the Woolaroc took flight from the Oakland Airport to its destination in Honolulu. During the race, two planes crashed and three returned to Oakland for repairs. Twenty-seven hours and 17 minutes later, the Woolaroc landed in Honolulu, beating the other planes and winning the $25,000 prize. “Aloha,” a monoplane piloted by Marten Jensen, landed two hours after the Woolaroc.

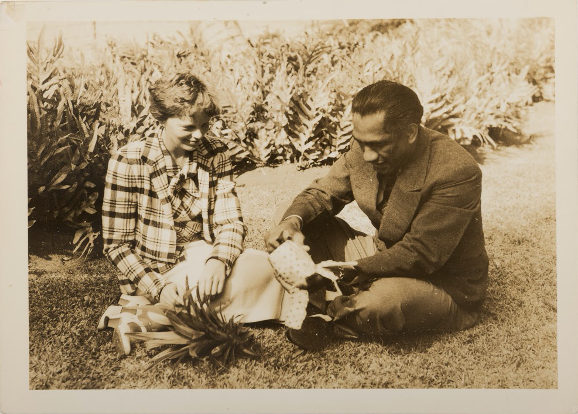

The photograph above depicts President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s (1882–1945) trip to the Territory of Hawaiʻi in 1934—making him the first sitting U.S. president to visit (Honolulu Star-Bulletin). Roosevelt and his family boarded the U.S.S. Houston in the Virgin Islands, passed through the Panama Canal and disembarked in Honolulu, Oʻahu on July 26, 1934. Although the President’s trip only lasted two days, he toured vast areas of both the island of Hawaiʻi and the island of Oʻahu.

Upon arriving in Honolulu, Oʻahu, President Roosevelt and his entourage were greeted by 60,000 citizens of the Territory of Hawaiʻi. They were also greeted in a traditional Hawaiian manner, with a fleet of outrigger canoes. His Hawaiian hosts adorned him and his entourage with lei, performed hula dances, and honored him at a lūʻau hosted at the historic Royal Hawaiian Hotel where he was staying in Waikiki Beach (FDR Presidential Library and Museum). President Roosevelt’s sons were even given a private surf lesson by famed surfer Duke Kahanamoku. The trip wasn’t entirely for leisure, the President met with newly appointed Governor Poindexter of the Territory of Hawaiʻi, who accompanied him for a motorcade tour of Oʻahu. He also met with the Commanding General of the Hawaiian Department of the Army and the Commandant of the Fourteenth Naval District at Pearl Harbor (FDR Presidential Library and Museum). Although the trip was promoted as a casual trip to Hawaiʻi with his family, the underlying purpose may have been to strengthen ties with the Territory for the eventual U.S. statehood of Hawaiʻi.

This photograph above depicts the day (August 12, 1898) the Hawaiian flag was lowered at ‘Iolani Palace and replaced by the American flag, marking the formal end of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. For many Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians), the day the United States illegally annexed the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi—thereby becoming the Territory of Hawaiʻi—is a heavy-hearted moment in Hawaii’s history. Almost 50 years prior to that day, fearing Hawaiʻi would become a European colony, Secretary of State Daniel Webster (1782–1852) sent a letter in 1842 to Hawaiian agents in Washington announcing U.S. interests in Hawaiʻi, and opposing annexation by another country (U.S. Department of State Archives). In addition, Webster suggested to the United Kingdom and France that no country should be allowed to engage in further colonization of Hawaiʻi. In 1849, the United States and Kingdom of Hawaiʻi signed the Treaty of Friendship that served as the basis of official relations between the two sovereign nations.

As part of the Treaty, American companies and missionaries were allowed by the Hawaiian monarchy to operate in Hawaiʻi. A prime location for whaling ships and access to land with fertile soil for sugarcane cultivation and sandalwood trade, Hawaii’s economy gradually became more integrated with the U.S. The Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 continued to give free access to the U.S. market for sugar, pineapples, coffee, and other products grown in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (U.S. Department of State Archives). It was during this period that American businessmen began to dominate the economy and politics in the Kingdom. Worried that Americans would further control Hawaiʻi politics, Queen Liliʻuokalani (1838–1917) began to write a new constitution. This constitution would return power to the Hawaiian monarchy and restore the voting rights of disenfranchised Native Hawaiians, Asians, and other citizens of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Outraged that the Queen would change the constitution to benefit Native Hawaiians, American businessmen led by Samuel Dole (1844–1926) began a movement to have the Queen overthrown. U.S. President Benjamin Harrison (1833–1901) supported the overthrow and dispatched sailors from the U.S.S. Boston to Hawaiʻi to surround the royal palace and aid with the overthrow (U.S. Department of State Archives). Refusing to give power to Americans, Queen Liliʻuokalani was arrested and spent her final days imprisoned in her home in Honolulu. On July 7, 1898, Hawaiʻi was annexed, helping the U.S. become a Pacific power.

In an effort to mend relationships with Native Hawaiians, President Clinton signed Public Law-103-150 (known as the Apology Resolution) in 1993. This resolution acknowledges the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi “occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and further acknowledges that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty” (U.S. Public Law 103-150 (107 Stat. 1510)).

One photo of Hawaiian cattle ranching I found interesting is the one above, of paniolos (Hawaiian cowboys) loading cattle onto cattle/freight steamer ships (c. 1912). During this ranching era, paniolos on the Island of Hawaiʻi loaded cattle one-by-one from row boats onto ships sailing to Oʻahu for meat processing. In this photo a bull is in mid-air, being hoisted onto a ship by two paniolos. This photo is important for documenting the early days of Hawaiian cattle ranching and the arduous profession of paniolos.

In pre-contact Hawaiʻi, all land and natural resources were held in trust by the aliʻi ʻai ahupuaʻa or aliʻi ʻai moku (high chiefs). The rights to the land and resources were given to the locals of the area. Land was divided by the ahupuaʻa system, which extended land boundaries from the sea to the mountains. The ahupuaʻa system depended on the absence of exploitation by locals ("A Short History of Cattle and Range Management in Hawaiʻi"). For example, fishermen only caught what they needed for survival, never depleting their resources and always leaving fish for others. Although traditional and efficient, the Hawaiian way of land management was replaced with the immigration of Europeans and Americans to Hawaiʻi. The new concept that land was valuable for extracting exportable resources like sandalwood superseded the traditional Hawaiian way.

Cattle first arrived in Hawaiʻi in 1793 when British Captain Vancouver (1757–98) gifted a herd of cattle to Kamehameha I. The cattle were placed under a 10-year kapu (taboo), which banned hunting and allowed them to reproduce (Maly and Wilcox 21). New cattle stock was introduced between 1793 and 1811, drastically increasing their numbers. The free roaming cattle (along with sheep and goats) created a severe impact on Indigenous homes, eating thatched dwellings, and eating produce farmed by local families. In order to control the cattle, Kamehameha I hired Mexican vaqueros from California to teach Hawaiians how to herd and handle cattle for ranching in 1815 ("A Short History of Cattle and Range Management in Hawai‘i"). As paniolos became experts in cattle ranching, the island of Hawaiʻi became prominent for ranching, where in 1851 there were over 20,000 cattle.

_3.jpg)

This Nekketsu postcard in the Blackburn Collection is a rare example of early (c. 1906) Japanese culture in Hawaiʻi. At a time when decisive U.S. policies aim to exclude “non-Americans,'' itʻs important for us to remember how immigrants have influenced and shaped this country. Japanese exchange with Hawaiʻi dates back to 1806, when the survivors of Japanese cargo ship, the Inawaka-maru, became stranded on Oʻahu after 70 days adrift. King Kamehameha I (1782–1819) allowed the Japanese merchants and sailors to stay in Hawaiʻi, delegating the responsibility of their well being to Maui high chief, Kakanimoku (1768–1827). Since these Japanese citizens were treated well by Kamehameha I, the Japanese Empire allowed for an official Hawaiian delegation to Japan in 1866. This led to broad immigration from Japan to Hawaiʻi beginning in 1867. This first wave of immigrants came to Hawaiʻi as low-cost laborers to work on sugar plantations. Once the mistreatment and exploitation of Japanese workers in the plantations was reported, the Emperor banned further immigration to Hawaiʻi lasting from 1869 to 1885 (Children of gan-nen-mono: The first-year men). Once the ban was lifted, an estimated 29,000 Japanese men and women immigrated to Hawaiʻi to work the sugar, pineapple, and coffee plantations. Many workers returned to Japan when their three-year plantation contracts expired, but some stayed in their new home of Hawaiʻi. These immigrants are known as the Issei (first generation) and their children who were born in Hawaii, are known as the Nisei (second generation).

Takei Nekketsu (1879–1961) was an Issei merchant, patent attorney, journalist, and map maker based in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi ("Tour Honoluluʻs Japanese Food Scene"). In 1915 Nekketsu owned a kimono and dry goods store on the corner of River St. and Pauahi St. in Honolulu. He traveled around Hawaiʻi on foot, taking photographs and making maps in Japanese for the local immigrant community. In addition to map making, he wrote some of the earliest Japanese language histories of Hawaiʻi ("Tour Honolulu’s Japanese Food Scene"). While traveling between plantations and Japanese communities he documented oral histories and records of Japanese daily life in Hawaiʻi. These stories were published in Japan, making him the most popular Japanese writer in Hawaiʻi at the time ("Tour Honolulu’s Japanese Food Scene").

When Japanese immigrants arrived in Hawaiʻi, there were no organizations or resources to help them adjust to their new lives on the island. To fill this gap, Nekketsu created the first maps of Hawaiʻi, Honolulu, and Japantown (today’s Chinatown) in Kanji for recent immigrants. These maps not only had place names in Kanji, but also featured Japanese-owned businesses.

King David Kalākaua (1836–1891), also known as the Merrie Monarch, was the last king of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. He is also remembered as the first Hawaiian monarch to travel around the world to meet with foreign leaders and dignitaries in Asia, the Middle East, and Europe (The Pacific Commercial Advertiser 1881). In 1881 he took a 281-day trip intended to create relationships with world leaders and encourage the immigration of contract laborers to Hawaiʻi. King Kalākaua and his royal entourage left Hawaiʻi in January 1881 for San Francisco, California, where he toured for one week. Following his trip to San Francisco he traveled to Japan, China, Hong Kong, Thailand, Singapore, India, Egypt, Italy, England, and Portugal to name a few. He ended his trip where it had started, San Francisco, California. In Portugal, he and his staff had the most successful immigration talks and negotiated a treaty of friendship and commerce with Hawaiʻi that provided a legal framework for the immigration of Portuguese laborers to Hawaiʻi (The Pacific Commercial Advertiser 1881). Other countries King Kalākaua was able to make immigration agreements with were China, Japan, Korea, and Spain.

During this trip, Kalākaua traveled twice to San Francisco, where photographer Isaiah West Taber’s studio was located. The Blackburn Collection contains a couple of photos of King Kalākaua with Taber’s studio name printed on it, but there is no guarantee that this photo was taken during Kalākauaʻs 1881 trip. The year before, in 1880, Taber took a six-week photographic trip to Hawaiʻi where he photographed members of the royal family, including King Kalākaua (Pioneer Photographers from the Mississippi to the Continental Divide). Since there is no way to know if the photo was taken in 1880 or 1881, I decided to date it “c. 1800.”

Future Research

These photographs are only a few of those that represent the unique history of Hawaiʻi. Although it was extremely difficult to choose only eight photographs (out of more than 9,700) to showcase in this blog post, I hope this small sample demonstrates the scope and invaluable importance of the Blackburn Collection (and what it can contribute to research on Hawaiʻi history).

The next steps in this project are to continue researching the remaining photographs of Hawaiʻi and to convene our Cultural Advisory Committee. After we have provided basic descriptions of the Collection’s Hawaiʻi photographs, we will move on to researching photographs from Samoa, Tonga, Aotearoa (New Zealand), and other Pacific nations. As an Indigenous researcher and recent graduate, I feel extremely grateful that I was given the opportunity to research this significant collection and that I get to share my experience with the public in this blog. My goal is always to continue LACMA’s high standard of collection and curatorial research while critically analyzing the photographs from an Indigenous perspective. I hope you enjoyed reading about Hawaiʻi history and I look forward to writing my next blog post.