Lee Alexander McQueen (1969–2010), the iconic designer of the eponymous fashion label Alexander McQueen, grew up in London’s working-class East End. Interested in fashion from a young age, McQueen is part of a long history of queer men in fashion design, including Gianni Versace, Yves Saint Laurent, and Marc Jacobs.¹ McQueen was publicly out throughout his career, once stating, “I think before you get onto a public platform, you have to deal with yourself before you put yourself out there. Things like sexuality always come out, and you come off worse by not being true to yourself… Yes, I think my sexuality has helped my designs.”

Alexander McQueen’s collections are known for their outlandish designs, vivid storylines, and cinematic stage effects. From a mythical journey across the Russian tundra into Japan in the Scanners collection, to a world where humans have adapted to live in water due to increasing sea levels in Plato’s Atlantis, McQueen embodies the legacy of what Angela Hesson calls the “queer fantastic.”

“Imagination and fantasy have long existed as sites of queer possibility, within which queerness is figured through transformation, ambiguity, surfaces and symbols, rather than merely through real-world acts or identities,” she writes.²

McQueen’s collections, deeply autobiographical as well as imaginative and fantastical, were informed by a career-long ethos of designing for the postmodern “femme fatale.”³ The fear and mystique surrounding the femme fatale were rooted in anxieties dating to the 19th century’s first wave of feminism and economic and sexual emancipation of women, as well as widespread outbreaks of syphilis. This rendered feminine sexuality toxic, and women carriers of disease, a sentiment echoed for the queer community two centuries later with the HIV/AIDS crisis during the 1980s and into the 90s.

As McQueen remarked, “there’s a witch hunt for every gay with HIV.”⁴

By recasting his models as dominant and confident subjects, McQueen subverted norms of women’s dress which perpetuate a status of submissive, demure objects. When accused of misogyny in his career, McQueen was quick to argue against it, saying “They didn’t know me. They didn’t know what I had seen in my life… I am constantly trying to reflect the way women are treated. It’s hard to interpret that in clothes or in a show, but there’s always an underlying, sinister side to the [woman’s] sexuality because of the way I have seen women treated in my life.”⁵

Currently on view in LACMA’s Resnick Pavilion, Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, Muse displays garments designed by McQueen, gifted by Regina J. Drucker, alongside artworks and objects in the museum’s permanent collection in thematic conversations. Though a variety of themes are explored throughout the exhibition, the case studies below illustrate how McQueen—informed by queer traditions in fashion and art—sought to uplift women through his designs.

The Widows of Culloden, Fall/Winter 2006–7

Alexander McQueen often looked to his ancestry for inspiration.⁶ The Fall/Winter 2006–7 collection The Widows of Culloden draws upon his Scottish heritage, particularly the Jacobite Risings of the Highlanders, which ultimately reached a climax during the 1745 Battle of Culloden. In the collection, McQueen featured the MacQueen clan tartan, as seen in the skirt featured in this Women’s Ensemble.

The collection also includes elements like fur, feathers, leather, and knits to allude to Scottish gamekeeping and hunting traditions.

The Battle of Culloden and the following Highland Clearances were devastating.“What the British did there was nothing short of genocide,” McQueen once said.⁷

While history often centers the male warriors who fought and died in battle, McQueen’s collection shifts the focus to the widows left behind. The show imagines the spirits of these women as they haunt the Highlands, and awards their ghosts a sense of transhistorical agency through memory. In the show’s finale, a hologram of a floating Kate Moss dressed in a flowing gown had an airy, ethereal feel, further cementing the otherworldliness of the models and, in turn, the widows of the Highlands.

In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692, Fall/Winter 2007–8

After discovering an ancestral connection to three women executed in the Salem witch trials of the 17th century, Alexander McQueen dedicated his Fall/Winter 2007–8 collection to exploring and reclaiming imagery related to witchcraft. Again, McQueen’s models became the phantoms of women put on trial, powerful and defiant as they walked the runway. In two dresses from the collection, a beaded motif that resembles hair, or perhaps flames, serves as a reference to the executions. Sentenced women had their hair forcibly removed, as it was believed they were powerless without it. While the accused were hanged in the American colonies, British “witches” were infamously burned at the stake.

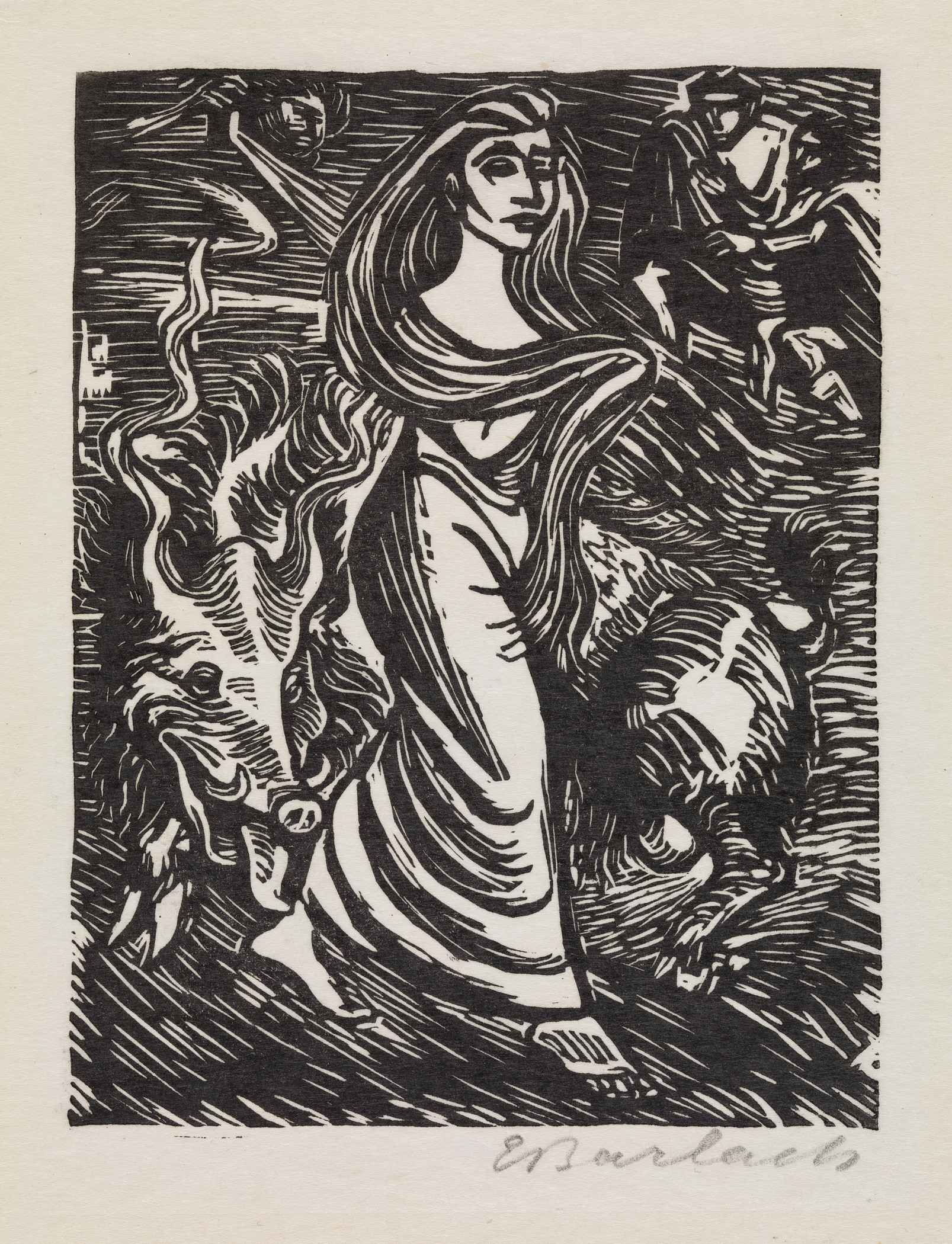

Hair has long been associated with a dangerous femininity, a trait that served as a leitmotif for pre-Raphaelite Western artists, but was later reclaimed and eroticized in the Edwardian fin-de-siecle period by queer artists. This was part of a fascination with “mythology and fairytale as realms of freedom and fluidity, exempt from moral structures of contemporary society” among queer artistic circles.⁸ In particular, images of Lilith⁹ recirculated during the latter period, her long hair now a symbol of virility and strength, as illustrated by Ernst Barlach’s 1922 woodblock print, Lilith, Adam's first wife. In his collection, McQueen continues this tradition of embracing previously villainized symbols of femininity by celebrating them on the runway.

(Wo)Menswear: Adapting Men’s Tailoring for the Woman’s Silhouette

Having trained as an apprentice on London’s Savile Row at just 16, McQueen appropriated aspects of men’s tailoring for women’s silhouettes. The designer continued the queer tradition of mixing masculine, feminine, and androgynous styles. Some historic examples include the 1920s la garconne style popular among lesbians and Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking Suit, as well as much earlier styles like the menswear-inspired jackets of the 17th century women’s riding habit.

This dress from Spring/Summer 1998, which emulates the jacket of a men’s suit, illustrates this concept of molding a staple of menswear into a feminine style. Additionally, McQueen commonly turned to historical silhouettes in his collections, as seen in this jacket inspired by men’s Elizabethan doublets.

McQueen repeatedly depicted masculine archetypes on the womenswear runway. These include the Scottish Highlander, the American Western outlaw, the Japanese samurai, and the Spanish matador, as seen in this jacket that references the traditional shortened chaquetilla worn by male bullfighters.

By reworking these classically masculine, often aggressive styles for the feminine, Alexander McQueen recharacterizes and emboldens the women wearing his designs.

LACMA wishes you a happy Pride Month. You can see these pieces and more McQueen fashions, alongside the artworks in conversation with them, now at the exhibition Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, Muse, on view through October 9, 2022.

1. While it has long been an unspoken cultural tradition to assume that gay men are drawn to fashion, fashion theorist Valerie Steele points out that queer people “had to be hyper aware of how to read and analyse clothes so as to dress in a way that would allow them to communicate with other people but not to be recognised by a homophobic society.”

2. Hesson, Angela. “Queer Fantastic: Imagination, Metamorphosis, Magic.” Queer: Stories from the NGV Collection, 2022, pgs. 314–345

3. Fashion theorist Caroline Evans defines the “femme fatale” as “Femme fatale… whose terrifying allure was fatal to men… Her highly sexualized appearance was a defense, but one which shaded into a form of attack.”

4. Big Magazine, 2007

5. Independent Magazine: Fashion, 1999

6. McQueen’s mother, Joyce, was a genealogist and social historian who traced his family’s lineage back to the French Huguenots. She frequently shared these discoveries with her son, and these family connections informed the themes of many collections, such as Highland Rape collection of Fall/Winter 1995–6.

7. Independent Magazine: Fashion, 1999

8. Hesson, Angela. “Queer Fantastic: Imagination, Metamorphosis, Magic.” Queer: Stories from the NGV Collection, 2022, pgs. 314–345

9. Lillith, according to Judeo-Christian mythology, was Adam’s first wife, expelled from the Garden of Eden by God after refusing to obey her husband. Her demonic reputation has attached her to several myths including coercing Adam into illicit sexual acitvites, haunting deserted regions and attacking children, as well as starting a race of wicked children with Satan.