An unexpected and undeniable presence in The Space Between: The Modern in Korean Art is the ubiquitous appearance of women throughout the show. While we knew that the introduction of female artists by name would be a mindful inclusion for the modern era, the predominance of its subject matter was not consciously conceived when organizing the exhibition, but when the show was installed, I couldn’t not see it.

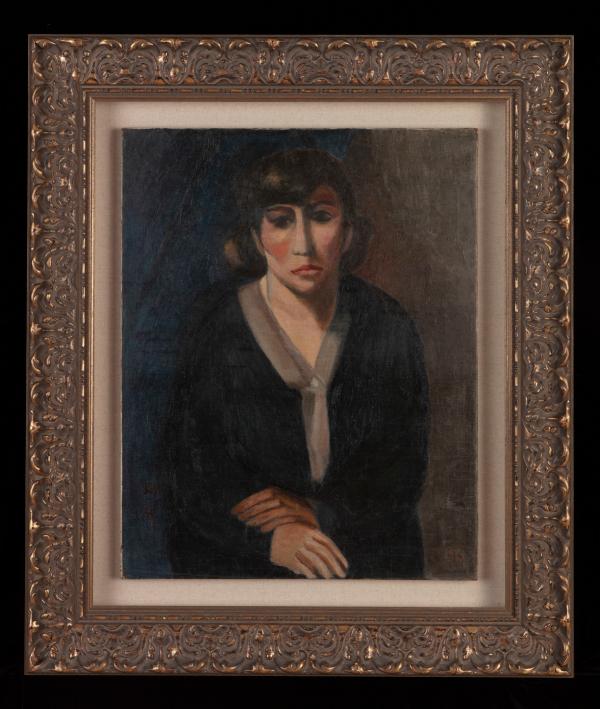

In The Modern Response, the second section of the exhibition, it’s hard to miss the first self-portrait by female artist Rha Hye-seok (1928), the nude bathers in Sunset (1916) by Kim Kwan-ho, and the photograph by Hyun Il Yeong, Untitled (Korean Skirt and Socks) (1950s, printed in 2022), intimating an unseen woman by the mysteriously and carelessly dropped (staged on not) traditional woman’s hanbok on the floor. Displayed nearby is the photograph of the glowing face of a young female face bathed in white by Jung Hae Chang, Lady (1930s).

As The Modern Response continues, works in colored inks, a then-new category introduced to Korean artists via Japan, seem to strongly suggest that the subject of women depicted by both male and female artists was expressed with great interest. Of particular fascination is the traditionally dressed figure with her back to us holding a Japanese origami crane in Lady (1942) by female artist Park Rehyun. Why did she choose to paint a woman this way? On the adjacent wall, Paradise (c. 1936) by female artist Paik Nam-soon incorporates a Fauvist style to realize her utopia but holds on to the traditional Korean folding screen format to achieve a larger-sized work.

On a deep orange wall on the perimeter of The Modern Momentum section, a family of birds is happily nestled among trees in Birds in the Woods (1950), a work by female artist Lee Hyunok. Lee breaks the long established male succession of ink artists by being recognized as the art student of the legendary ink master Lee Sangbeom whose work Autumn Landscape (1940s) is featured in the previous Modern Response section.

Statue of a Grandmother (1936) by Kim Chung Yung is the earliest surviving sculpture of the modern period. The bust of the artist’s grandmother located in The Modern Response galleries continues the inherited principles of Academic Realism nearly two decades later. In large part, Korean society’s reluctance to accept sculpture to be other than Buddhist sculpture accounted for its slow acceptance.

By the time we come upon the more developed sculptures in the open space of The Modern Momentum, female sculptor Kim Chung Sook’s Mother and Child (1955) echoes this universal theme gracefully, in the medium of aged copper. When viewed together with the large and later ink work Open Stalls (1956) by aforementioned female artist Park Rehyun behind it on the dark violet wall, we can instantly see maternal love paired with an emerging sense of modern independence, whether it was something yearned for or a reflection of reality. Another of Kim’s sculptural works, Reclining Woman (1959), in the final gallery, Evolving into the Contemporary, uses her preferred medium of wood. As the first Korean sculptor to be trained in the U.S., she also learned and brought to Korea the technique of welding metal, a practice we see in the metal works throughout the show.

In The Pageantry of the New Woman (Sinyeoseong) gallery, two unmissably large works by Lee Yootae, Research and Composing a Poem in Response, both completed in 1944, one year before Korea was liberated from Japan, boldly evidence the new professional career opportunities for women and the ways women started to choose to spend their time. These options were a direct outcome of allowing women in Korea to officially receive an education, a key cornerstone of the New Woman sensation created and conceived of by men that failed to gain firm enough footing to become a full-fledged feminist movement. On the opposing wall, a young Choi Seunghui, the most photographed woman in Korean photographic history, is spotlighted by pioneering photographer Shin Nakkyun. In this vintage photograph, Choi epitomizes the “look” of the New Woman with her short, bobbed hair style and short Western dress unashamedly bringing attention to her exposed leg. All the works in this gallery attest to the emerging role of women in advancing the country into modernization.

The women in Han Youngsoo’s photographs in the section Evolving into the Contemporary, taken in what I have termed an “unconscious moment,” consciously playing off of Henri Cartier Bresson’s “decisive moment,” further attest to the fluid embrace of women wanting to move forward in time with modern styles and yet happily affirming the timelessness of women in general.

The works of six female artists are featured in The Space Between—Paik Nam-soon, Rha Hye-seok, Park Rehyun, Lee Hyunok, Rhee Seundja, and Kim Chung Sook. Regrettably there are others that could not make it into the exhibition. Yet, it is difficult to simply conclude that allowing women an education directly accounted for women to be trained in art schools. The deliberate introduction and integration in the exhibition catalogue of the interview with Nora Noh, Korea’s first fashion designer, who moved a generation of women from traditional dress to Western designs, was herself the epitome of the New Woman. With ongoing strides to rebalance female representation and voices in art history, this crucial subject in Korean art is yet to be satisfyingly made known. Its understanding and scholarship would richly add to the world’s understanding of female artists. And within East Asian history, the research would provide unmistakably pronounced cracks in the “monolithic wall” of the still lingering male-dominated legacy of Joseon Neo-Confucianism.

The Space Between: The Modern in Korean Art is now on view at LACMA through February 20.