For National Hispanic Heritage Month, which takes place September 15–October 15, we’re sharing highlights from the museum's collection selected by LACMA staff members to commemorate the month and celebrate Hispanic and Latine art and culture.

Claudine Dixon, Curatorial Assistant, Prints and Drawings

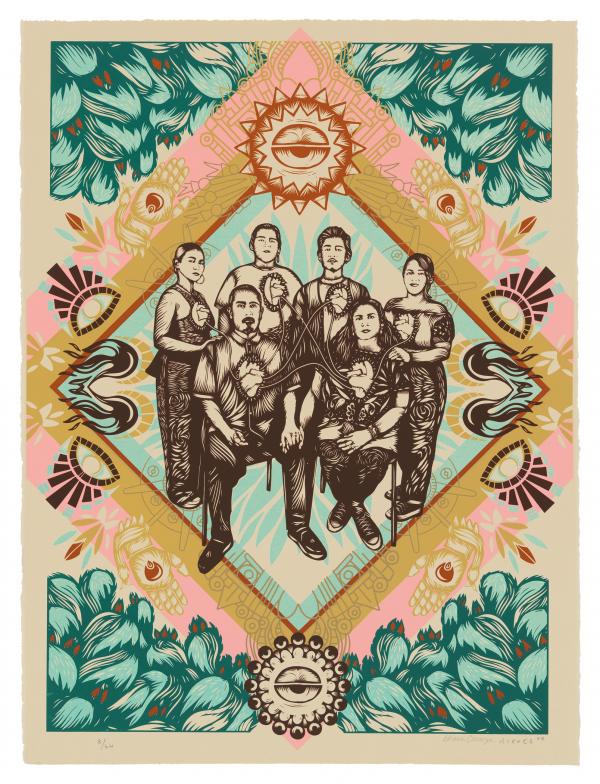

Kalli Arte Collective, Familia, 2022

The Kalli Arte Collective—a collaboration established by artists Alfonso Aceves and Adriana Carranza with their four children—produced the screenprint Familia (Family) in 2022. The image depicts the parents seated at center, their children standing behind them. The six figures are linked through the intertwining arteries between their hearts—a device made famous in works by Frida Kahlo. Surrounded by various objects that have distinct Mesoamerican symbologies yet also function as bold design elements, Familia expresses a strong familial bond—however it also harkens back to the past in acknowledgement of the artists’ Indigenous heritage and serves as a beacon for future generations.

In proclaiming an association to the past, present, and future, Aceves and Carranza told me that the impetus for the print stemmed from how best to express their creative energy during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, as they lived together in isolation from others. The artists explained that during this time they took many family photographs to document their interconnectedness and used one as the template for Familia, which was printed at Self Help Graphics & Art, a local atelier that champions the work of artists primarily from the Latine communities of Southern California.

Both Aceves and Carranza were born in Los Angeles of Mexican heritage and met at Theodore Roosevelt High School in Boyle Heights. Neither had any formal art school training and initially never imagined they could become professional artists—what they have learned of their craft is entirely self-taught, developing from a creative drive that allowed their dream to materialize.

Alicia Vogl Saenz, Manager, Family Programs

Luis Cadena, Woman Spinning (Hilandera), 1859

Every time I meet a fellow Ecuadorian in Los Angeles, I get super excited. Even though this city is predominantly Latine, there just aren’t that many of us here. (I’ll stop here for full disclosure: I’m half Ecuadorian. My mother was Ecuadorian and my father was from Czechoslovakia and given asylum in Ecuador in 1939. Think of me as an Ecua-Czech.)

Imagine my joy when a few years back I turned a corner in LACMA’s galleries and saw the painting Hilandera (Woman Spinning) by Luis Cadena, who was, you guessed it, an Ecuadorian artist. At first, I was struck by the shape of her face and her nose. She felt familial, like she could be a cousin. Her long black hair, parted in the middle and gathered at the back of her neck, reminds me of the way my cousins wore their hair in the 1970s. I stopped to look and read the label. She’s spinning yarn; I imagine that it is alpaca wool. Her expression is quiet as she kneels on a fleece with a cute white dog, asleep. Even that dog looks like the one I had when I lived in Quito as a teenager. Although the painting is from 1859 and no one in my family spins yarn, except metaphorically in stories, I feel a kinship.

Rosanne Kleinerman, Teaching Artist

Wifredo Lam, Tropic (Trópico), 1947

Trópico, a large canvas by Wifredo Lam, is a gem in LACMA’s permanent collection. Lam, born in Cuba, studied art in Havana and Spain. He went to Paris where he became friends with Picasso and many of the surrealists of the day.

In 1947, the year Trópico was made, Lam’s painting style evolved. He was able to marry elements of surrealism and cubism with ideas from Oceanic and African art into a vocabulary all his own.

Wifredo Lam lived an extraordinary life that took him all over the world. When he returned to Havana, he revisited Afro-Cuban rituals of his childhood. He was able to synthesize his varied interests in life and art into an exceptional body of work.

I always visit Trópico when I’m in BCAM. As a painter, I stand before it, transported. I think about travel and experiences, about home, about taking ideas, memories and cosas, and somehow turning it into something new.

We are so lucky to have this important painting in LACMA’s collection. It’s always a joy to pause and dream for a moment in its presence, and to introduce my students to the work of Wifredo Lam.

Trina Calderón, Senior Coordinator, Public Programs, Music & Film

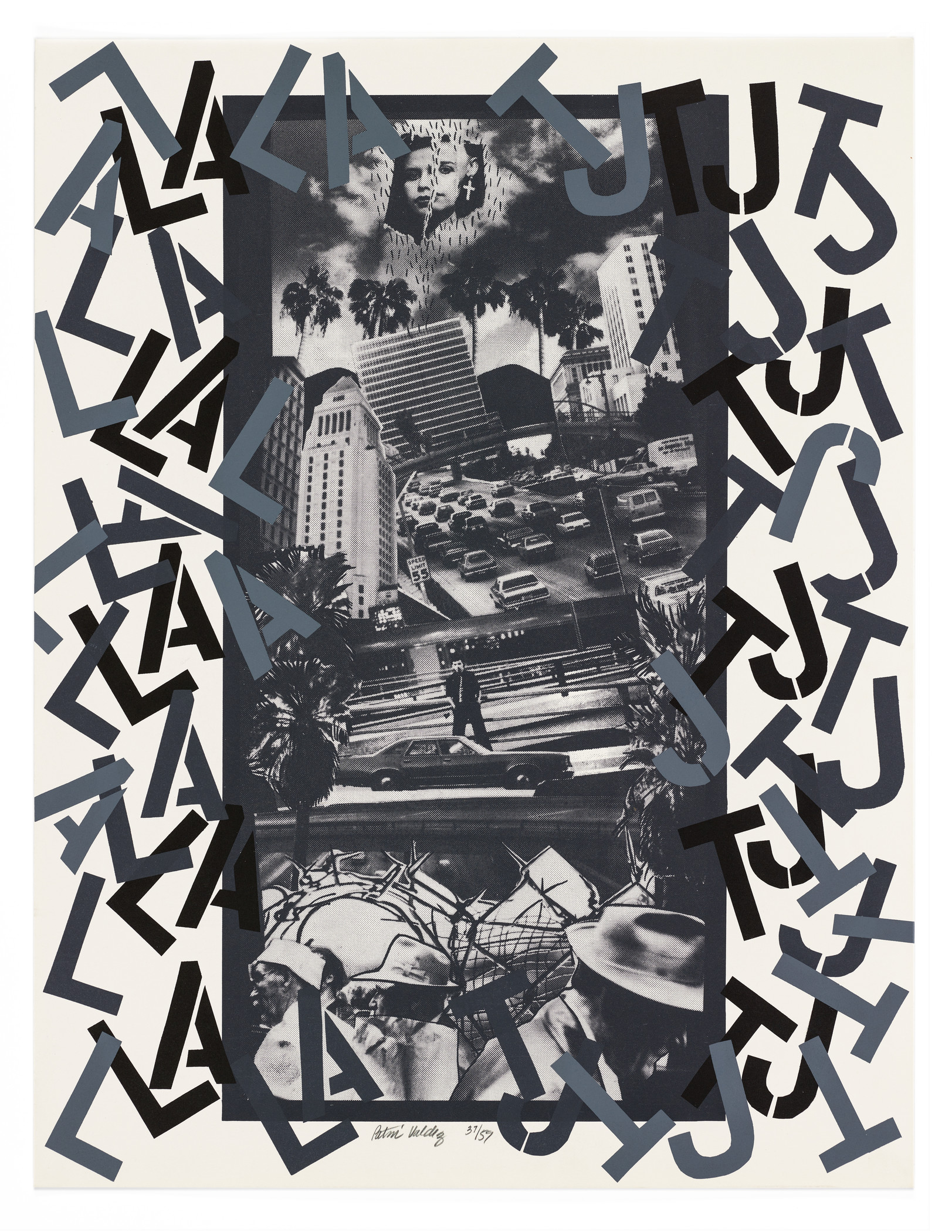

Patssi Valdez, L.A./T.J., 1987

This screenprint by Patssi Valdez makes me think about cultural division created by freeways and borders. I see the crossroads of two cities not very far apart. I've grown up with these man-made boundaries and staged palm trees that force conversations about the authenticity of our identity and location. I feel a disconnect within the walls of skyscrapers and stretches of cement highways; they're in the way of my relationship to nature and my community. I've driven all over Los Angeles and across the border to Tijuana many times, through the fence and the barbed wire to see faces that look like the same faces in Los Angeles. The collage of images with the border at the bottom remind me of the way people can be cut off and denied instead of cared for and acknowledged. I love the way Valdez used "LA" and "TJ" as a frame for this image, tying the well-known acronyms together to possibly make the viewer wonder about why these cities are different at all.

Olga Ordaz, Visitor Services Associate

Frida Kahlo, Weeping Coconuts (Cocos gimientes), 1951

There is always a bowl of fruit on a Mexican kitchen table.

Frida Kahlo’s Weeping Coconuts reminds me of the idea that strength means toughness and lack of emotions, when, in fact, it takes a lot of courage and strength to be vulnerable and open to others.

In difficult situations we often find ourselves detaching from our emotions, closing ourselves off to others and slowly building a hard exterior as a survival mechanism. At times, this is necessary to protect ourselves and to heal. However, if we move through life closed off to the world, we may start to feel too comfortable, never allowing others to see us weak or vulnerable, creating a major impact on how we live our lives.

Humans are like coconuts. The outside is hard, but the inside is soft, sweet, and tender. No one would ever know this by just looking at a coconut. But, if we wait too long to drink the coconut water and to pry it open, the coconut will turn.

I have vivid memories of growing up in a Mexican household, a bowl of fruit always on the kitchen table. Inevitability, someone would reach for a piece of fruit, or someone would offer one. Then, the preparation would begin: peeling, cutting, seasoning. A meditative act that creates space for difficult conversations.

The kitchen table is where we pry ourselves open to others and allow ourselves to be weeping coconuts.

Claudine Dixon, Curatorial Assistant, Prints and Drawings

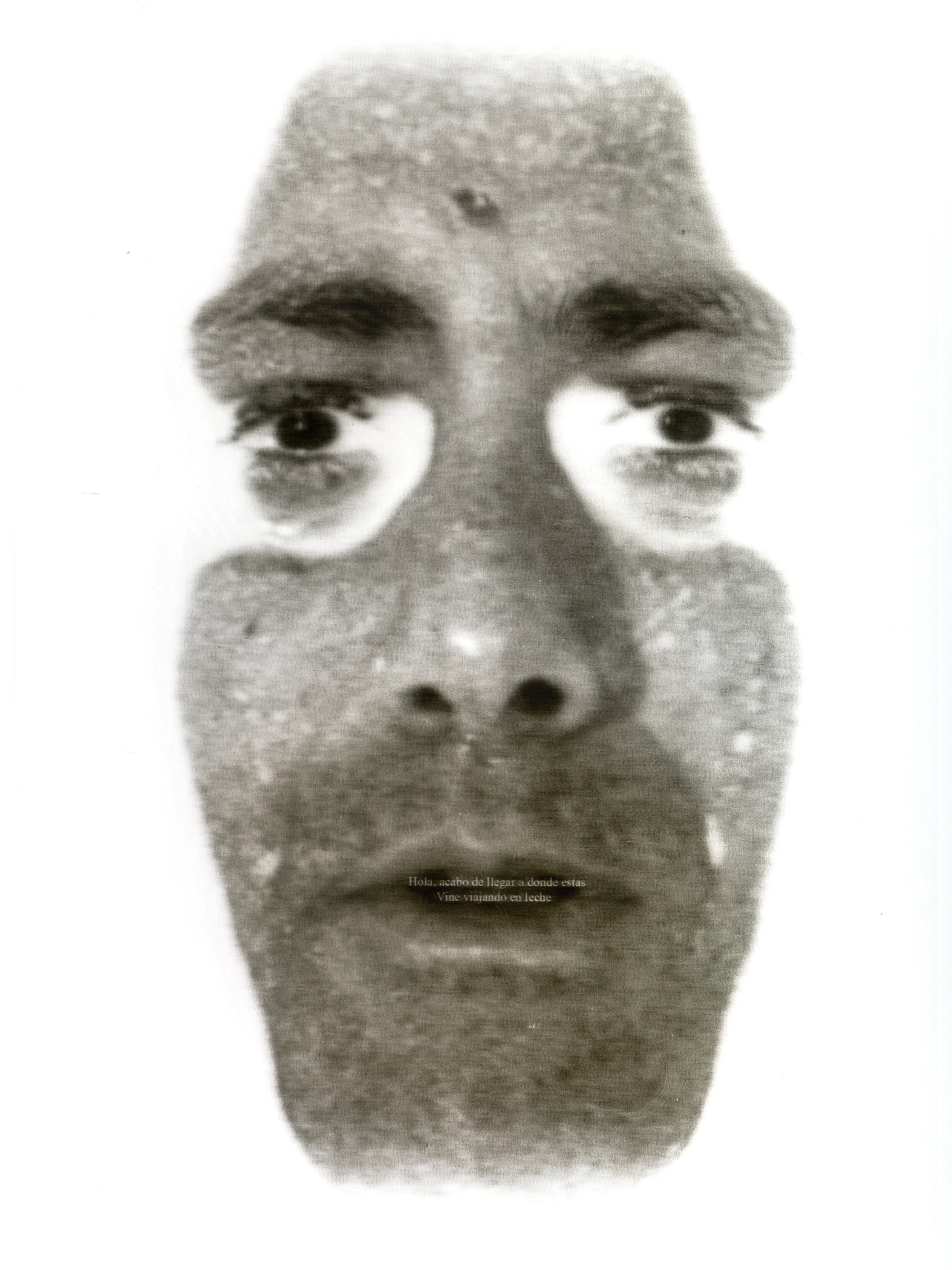

Fabián Cereijido, Viaje en Leche, 2012

The photolithograph on glass by the Argentinian-born/naturalized American artist Fabián Cereijido entitled Viaje en Leche (Voyage in Milk) caught my attention when I first saw it at El Nopal Press, the Los Angeles atelier established by Francesco Siqueiros. With Cereijido’s face emerging from a “milky” bath (made legible by the reflection of a white background), the image is both mesmerizing and disconcerting. Through our imagination we wonder if the face will continue to rise above the surface or if it will re-submerge into the liquid depths. As presented, the face hovers in a sort of never-never-land space, with tiny words between the lips expressing the artist’s greeting upon arrival to the observer. Learning about its genesis, inspired by an earlier video made by Cereijido, I was captivated by the meaning of the face, and how the artist’s own autobiographical narrative of displacement and assimilation (escaping the military dictatorship in Argentina, immigrating to Mexico as a teenager, and ultimately settling in the United States) might be suggested in this image.

Cereijido told me his collaboration with Siqueiros on the creation of this print came about when the printmaker equated the quality of liquid as congruous with glass—because of the translucidity of both elements. This complements the reference to milk as the universal source of life and nourishment, light and positivity, but as the artist explained, it also conceals darker depths (open your eyes while submerged in milk and you’ll only see blackness)—the yin and yang of our existence.