LACMA is deeply saddened by the passing of Frank Stella, a pivotal figure in the development of modern art since the late 1950s. Working in multiple mediums, Stella created an extensive body of work that has consistently challenged the conventions of art making. Over more than 60 years, he pushed the boundaries of Abstract Expressionism, helped usher in Minimalism, and continuously experimented with new materials, abstract forms, and innovative techniques.

By the time he was 23, Stella’s art was already being recognized for its innovations. Several of his paintings were included in the 1959 exhibition Three Young Americans at the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, as well as in Sixteen Americans at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1959–60), and he went on to have dozens of solo exhibitions and retrospectives (including two shows currently on view in New York). A frequent writer and speaker, Stella was the first artist invited to give the Charles Eliot Norton lecture at Harvard, in 1983 and 1984; those lectures were later published as the highly influential book Working Space.

While Stella found endless ways to reinvent his work, he devoted his entire career to abstract art, and especially abstract painting. In the 1970s and ‘80s, when he shifted from flat paintings to three-dimensional works that took on sculptural qualities, he called them “maximalist paintings” or “painted reliefs.” As he explained to the New York Times in 1987, “No matter how sculptural or three-dimensional or projective they might be from the wall, the essential way that you look at them and address them is through the conventions of painting.”

LACMA is fortunate to have several works by Stella in its collection that mark important developments in the rich trajectory of his career. These include Getty Tomb (1959), on view in BCAM, Level 3, an example of his early Black Paintings series that was acquired through the Contemporary Art Council in 1963, four years after it was painted. Composed of parallel bands of flat black paint separated by thin lines of unpainted canvas, the Black Paintings were a radical departure from Abstract Expressionism, which had dominated art in the preceding decade. Free of narrative or symbolic allusions, the series called attention to the physical properties of paint and canvas, conveying Stella’s often-quoted statement that “what you see is what you see.”

Bampur (1965), from a small series known as the Persian Paintings, and Hiragla Variation I (1969), from the Protractor Series, reflect Stella’s ongoing formal experimentation with their bent and curved stripes of intersecting colors. His works from this period further extended the concept of the shaped canvas that Stella began exploring in the early 1960s, and they anticipate his increasingly complex investigations into geometry and space that define his later work. In the mid-1960s, Stella also began his prolonged engagement with printmaking, working first with Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles. LACMA is fortunate to have 29 prints by Stella in the collection, including many made at Gemini G.E.L.

Works such as Rozdol II (1973), from the Polish Village series, mark an important step in the development of Stella’s pictorial language. Moving away from an emphasis on two-dimensionality, the artist built up the surface of these collage-like constructions by applying materials including felt, cardboard, and plywood. These works are a precursor to Stella’s “maximalist paintings” or three-dimensional metal reliefs, such as Inaccessible Island Rail (1976) and Kagu (1979–80) from the Exotic Birds series. Projecting into the viewer’s space, these three-dimensional works comprise playful, swirling forms and painterly brushwork that recalls the graffiti of Stella’s New York City environment.

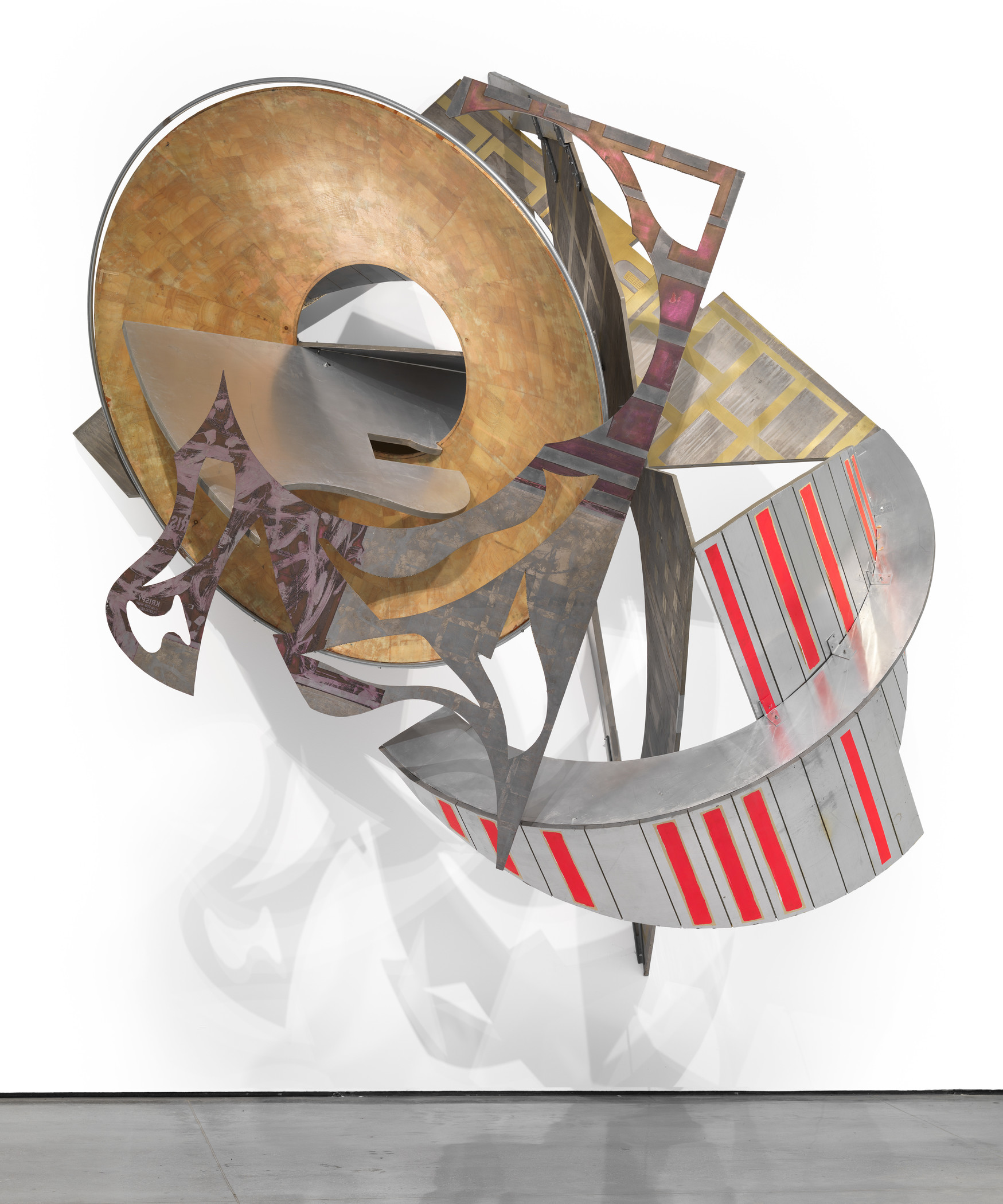

The monumental St. Michael’s Counterguard (1984) is from Stella’s Malta series, inspired by a 1983 visit to the Mediterranean island. Although sculptural in form, Stella considered St. Michael’s Counterguard a painting. Around the time he made this work, he stated: “What painting wants more than anything… is space to grow and expand into… Painting does not want to be confined by boundaries of edge and surface.”

K56 (large version) (2013), from Stella’s recent Scarlatti Kirkpatrick series, emphasizes the relationship between color, form, and space. The title of the series refers to 18th-century Italian composer Domenico Scarlatti and 20th-century harpsichord virtuoso and musicologist Ralph Kirkpatrick. K56’s vibrant, lyrical lines evoke musical composition, suggesting both the lively rhythm of a Scarlatti sonata and a swirl of gestural brushstrokes. Stella employed 3D printing technologies in the Scarlatti Kirkpatrick series, representing yet another new chapter in his artistic evolution and technical experimentation.

LACMA has been exhibiting Stella’s work for many decades, including the MoMA-organized retrospective Frank Stella: Works from 1970 to 1987 in 1989. St. Michael’s Counterguard and Inaccessible Island Rail were also included in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s recent retrospective of Stella (2015–16). All of the works above and others by Stella were presented at LACMA in the 2019 exhibition Frank Stella: Selections from the Permanent Collection, which brought many of these visionary works back on public view for the first time in over 30 years.