In this post, LACMA’s associate conservator of photographs, Elsa Thyss, explains the increasingly rare collotype print process after learning from Osamu Yamamoto, from Kyoto’s Benrido Collotype Atelier, the only fine-art printing studio producing color collotypes internationally. In an upcoming post, Thyss will also share some insights into collotypes from LACMA’s collection.

Collotype is a photomechanical printing technique, which means it combines photography and printing. Like lithography, it is a planographic printing process based on water's repulsion of oily ink, but instead of a lithographic stone, the collotype uses a gelatin-coated glass plate.

Last year, as part of the symposium “Photomechanical Prints: History, Technology, Aesthetics, and Use” at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, I took a one-day workshop on collotype prints. There, I learned about the challenges of this 19th-century process, which involves sensitized gelatin coated on glass to obtain a printing matrix. I knew about collotype printing from reading about it, but I had never seen someone demonstrate how to make them. The process of making collotype prints is arduous. The variables (therefore, the things that can go wrong) are countless: the gelatin concentration, the sensitizer formula, the processing water temperature and the duration of immersion, the amount of ink, and the pressure between the paper and the plate, among others.

So, why choose the collotype process to produce a printed image? Knowing how elaborate this technique is and how much expertise is required—master printer Richard Benson describes the process as “complicated, terribly unpredictable, and erratic at best”¹—why have artists, makers, and publishers selected the collotype process, among all the other printing techniques available?

Collotypes are made as follows: first, a glass plate is coated with a warm gelatin solution containing potassium dichromate. These chromium salts act as a sensitizer: they make gelatin harden when it’s exposed to light. Once the sensitized gelatin has cooled down and dried, the plate is exposed to light while in contact with a negative on a transparency. Then, the plate is washed in cold water to remove the chromium salts; the cold wash also spontaneously makes the gelatin crack into a network of reticulations, which will retain the ink in the next step. The gelatin is humidified with a mixture of water and glycerin and wiped off to remove the water on the surface. It is finally inked and then pressed against a sheet of paper to produce a print. During this last step, the oily ink only adheres to the hardened/hydrophobic areas of the gelatin (creating shadows). In contrast, the unexposed/hydrophile areas, soaked with water, repel the ink (creating highlights).

This video by the Benrido studio illustrates these steps.

Collotype printing originates from an 1855 patent and was developed for commercial use in the 1870s. Multiple variations of the process, monochrome and polychrome, were developed in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Collotype printing was used in various contexts, including commercial printing, artist portfolios, postcards, and book illustrations. It was particularly well suited for reproducing photographs because it produced images without a halftone screen. (Halftone produces images made of small dots). Its soft gradations also allowed high-quality reproduction of delicate artworks, such as pastels and drawings. However, the process remained challenging and expensive and was progressively replaced by offset lithography for most applications.

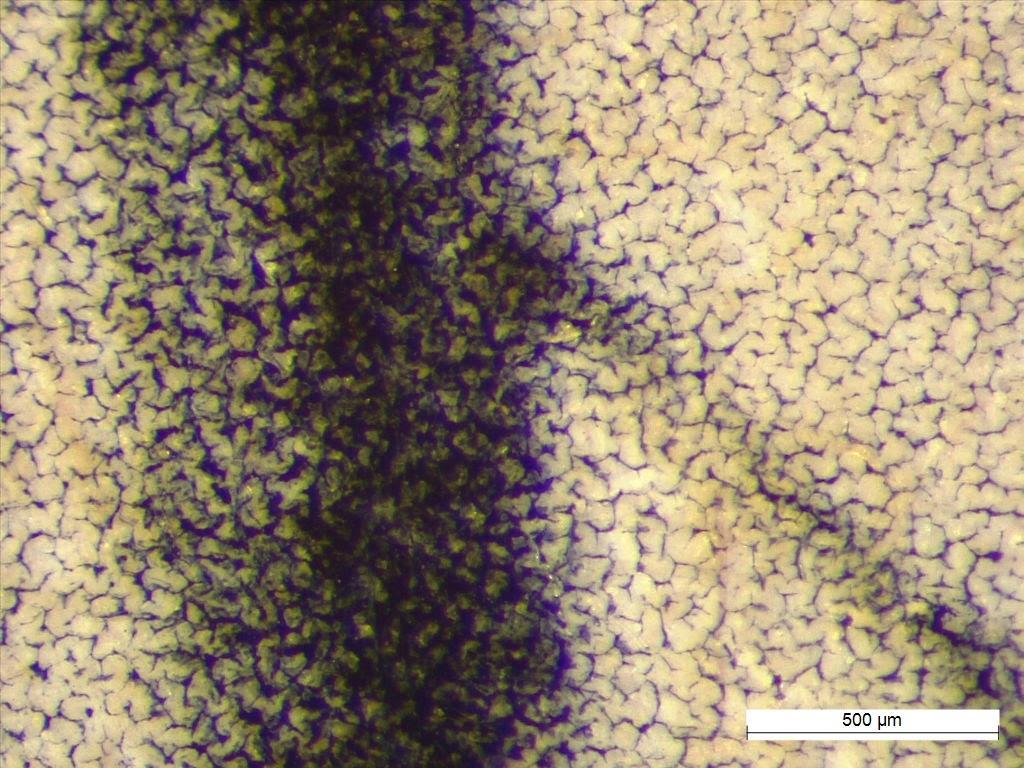

The most striking fingerprint of collotypes is the reticulation or “worm-like” pattern visible with a microscope. No plate mark is visible since it is a planographic printing process. Most collotypes are monochrome, but some are in multiple colors. One crucial technical characteristic is that after a few hundred prints, the gelatin started to deteriorate and become unusable, so the plate could only be used for short runs (a few 100 prints at most).

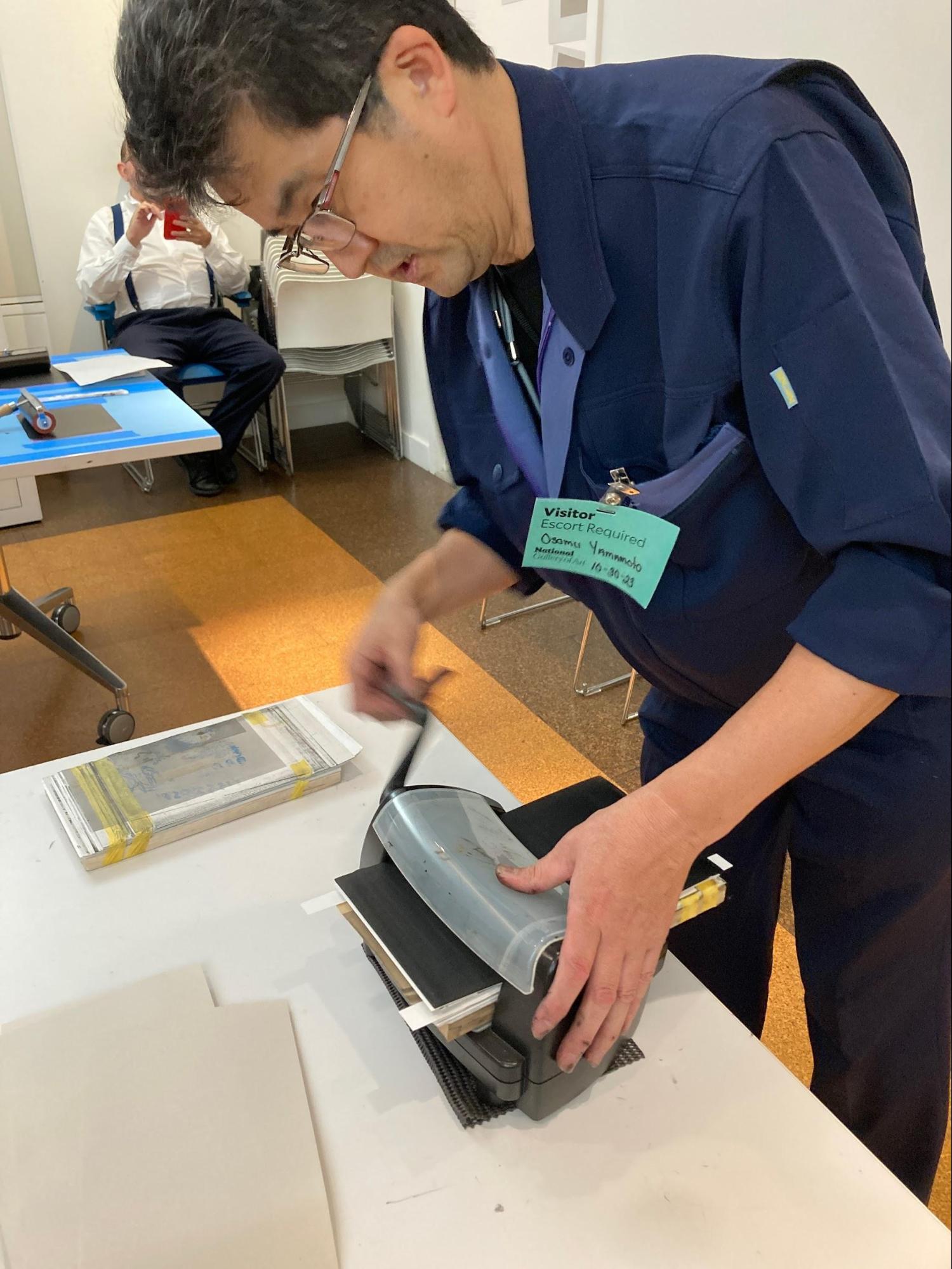

In October 2023, I took a workshop with Osamu Yamamoto from the Benrido Collotype Atelier, based in Kyoto, Japan. Benrido started producing collotypes in 1905. Today, Benrido is the only fine-art printing studio producing color collotypes internationally. The studio’s primary type of work is the reproduction of historical and contemporary artworks. In the last few years, the studio brought significant and impressive modern modifications to the historical process by developing a new photosensitizer safer for the human body and the environment than the historic potassium dichromate while maintaining the same level of printing quality.

Prior to the workshop, we were asked to send digital pictures to Benrido so that they could create a sensitized plastic film coated with selectively hardened gelatin matrices, also called tissues, so when we started the workshop, our personalized tissues were ready for a printing session!

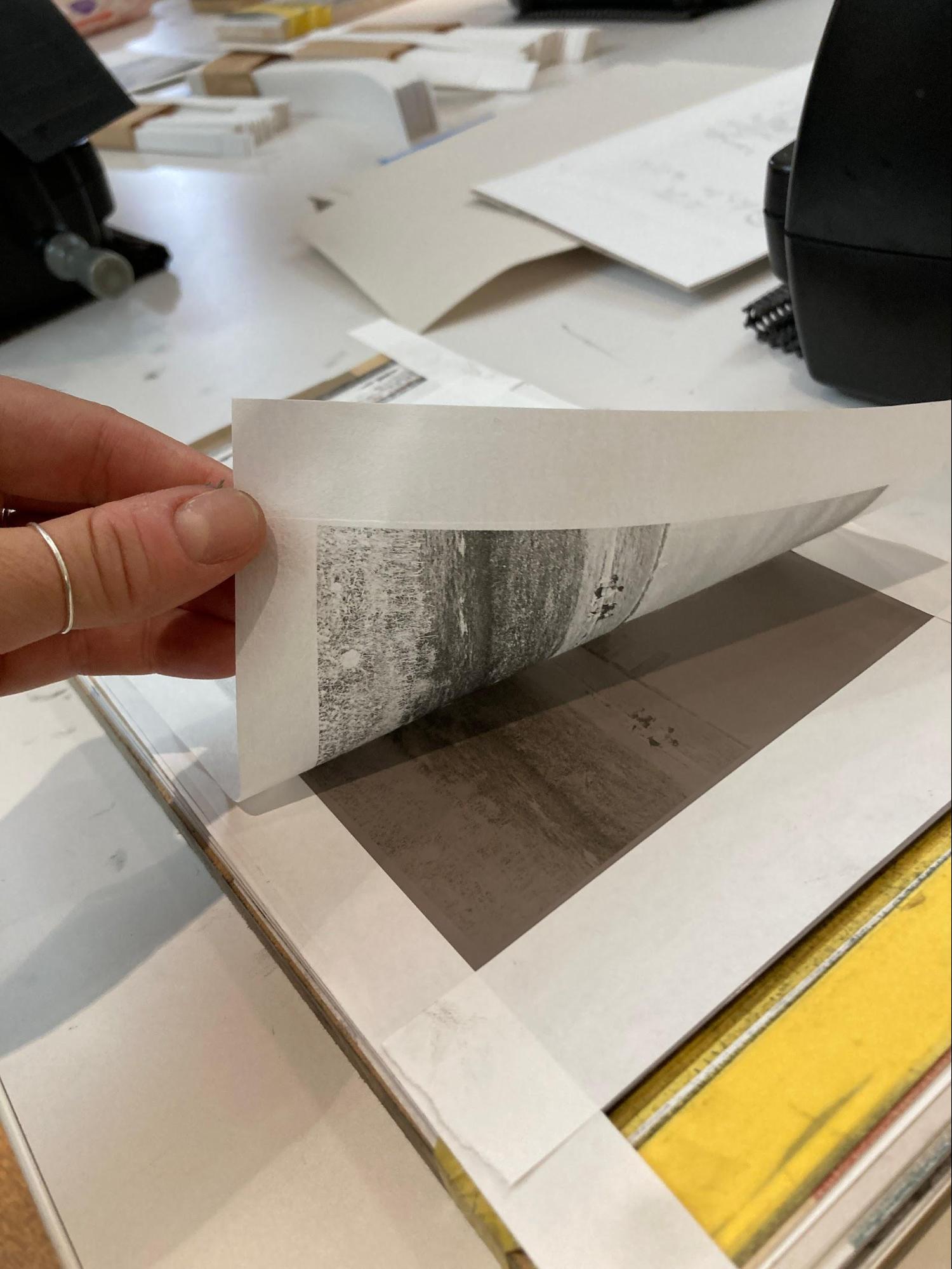

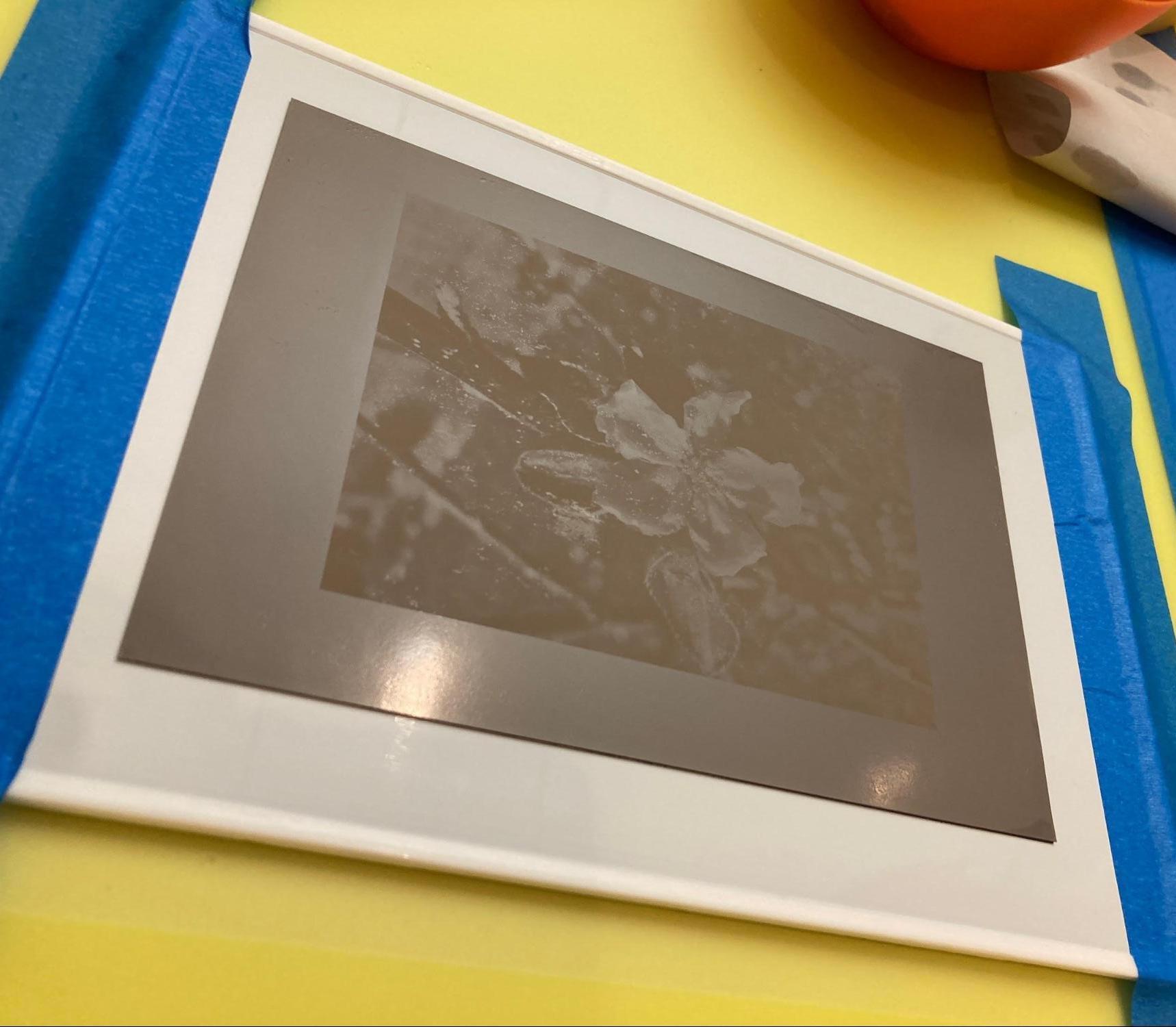

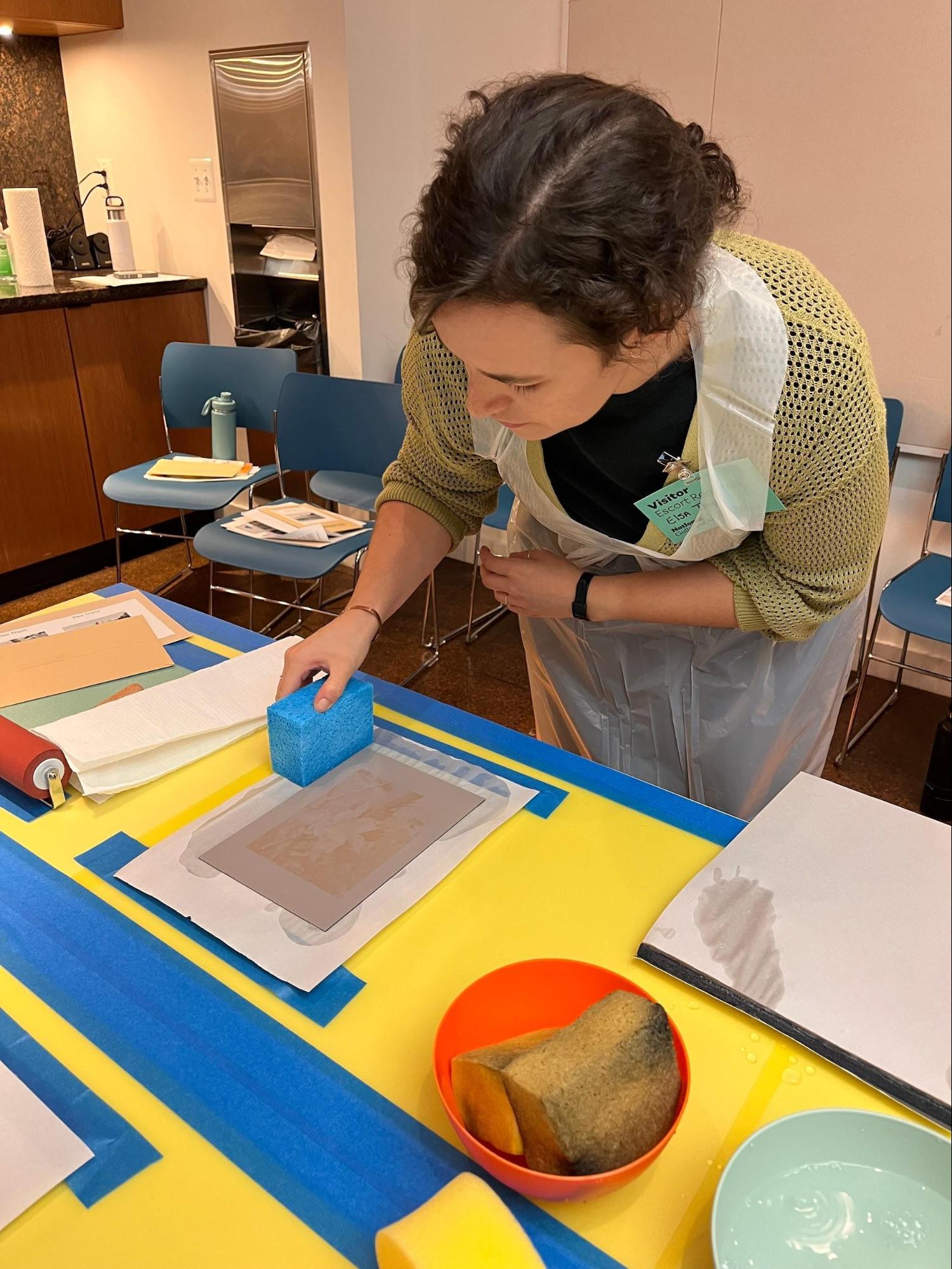

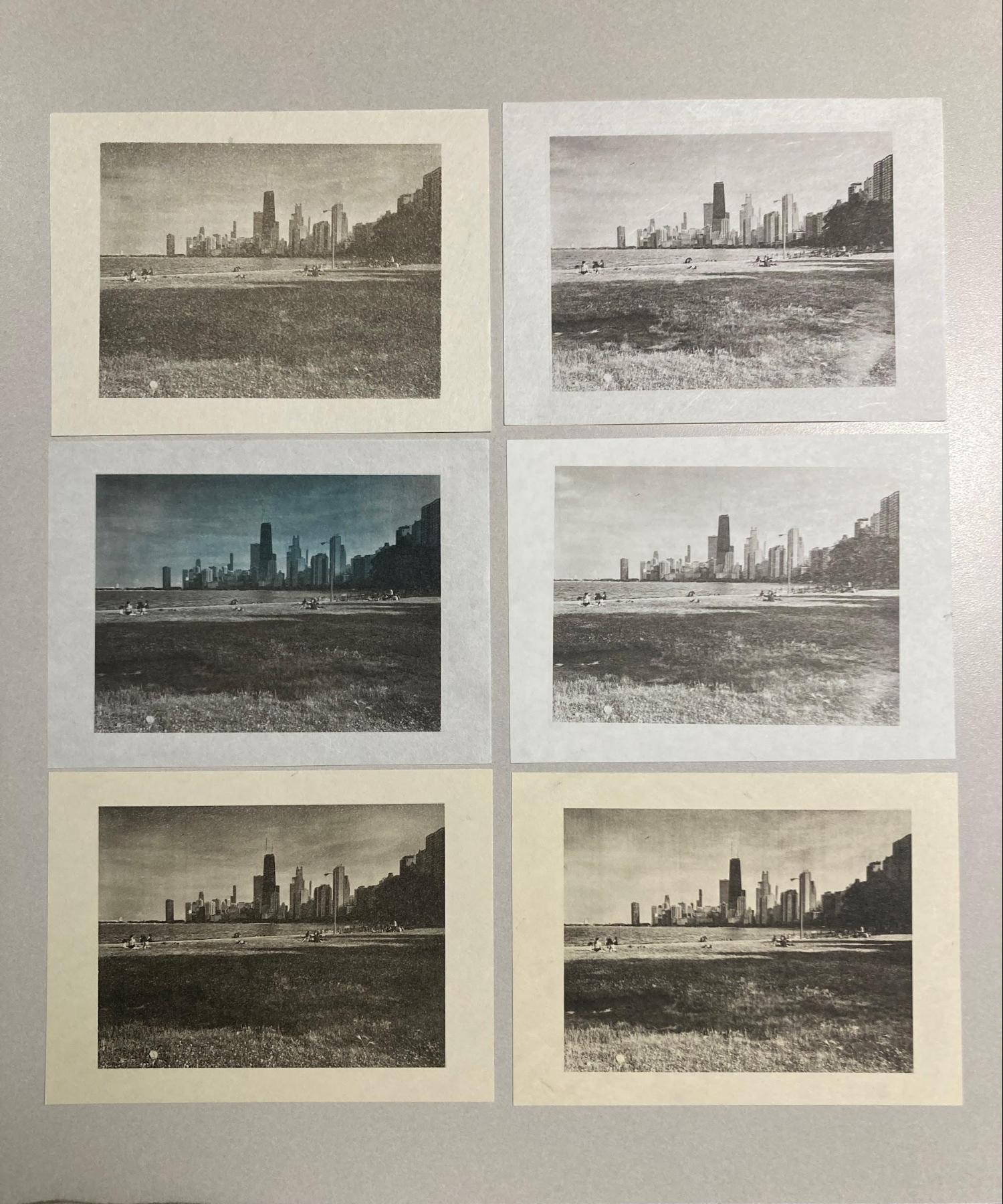

The first step was to humidify the tissue (the matrix plate) [image 1, above] generously with a water-loaded sponge containing a bit of glycerine [image 2]. After letting the gelatin swell in contact with the water, we inked the tissues using a rubber roller [image 3]. The tricky part was to apply the ink at the right speed: when the roller was passed slowly, it deposited ink on the surface, when it was rolled quickly, it picked up the ink back on the roller. The inked tissue was placed in contact with a sheet of Japanese paper. We placed the sandwich through a hand-activated roller press [image 4] and delicately separated the print from the tissue [image 5]. I experimented with printing different inks and papers from the same tissue, which gave me a sense of the infinite possible variations of contrast, color density, and detail level [image 6].

This experience offered me a glimpse into the efforts that go into the collotype-printing process. I realized how crucial the skills of the printer are in achieving a high quality print. The application speed and pressure of the rubber ink roller onto the matrix, the pressure of the paper against the tissue in the press, the paper thickness, and its capacity to absorb the ink, among many other parameters, all determine the print quality. From his decades of experience, Osamu could intuitively assess and adjust all these parameters to obtain an outstanding result. In contrast, I could only predict the outcome of my efforts once the paper was printed!

¹Benson, Richard. “Photography in Ink: Collotype.” The Printed Picture, 244–53. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2008.