As LACMA prepares for the 2026 public opening of the new David Geffen Galleries, the future home of the museum’s permanent collection spanning a breadth of eras and cultures, we’re sharing 50 iconic artworks that will be on view in the building over the next 50 weeks in the series 50 Works 50 Weeks.

Wrestlers (1899) is Thomas Eakins’s last completed genre painting, his last consideration of the male nude, and his last sporting picture. Born in Philadelphia in 1844, he emerged as one of the foremost figure painters of the late 19th century, dedicating much of his art and art instruction to the study of the nude. Considered in the trajectory of his oeuvre—from his first rowing pictures completed in the 1870s to his large-scale portraits of professional men—Wrestlers stands as a superb summation of the most significant themes of his career.

A lifelong enthusiast of wrestling, as both a spectator and participant, Eakins began accompanying his friend Clarence Cranmer, a local Philadelphia sportswriter, to boxing and wrestling matches in the 1870s. Cranmer later claimed that they had seen upwards of 300 live-fighting contests, and these matches afforded Eakins the opportunity to view partly nude male bodies in states of tremendous exertion, contortion, and duress. He believed that wrestling possessed a “purity” that set it apart from other sports and, in 1898, just two years after the first Olympic games in nearly one thousand years, he commenced a new series of sporting pictures.

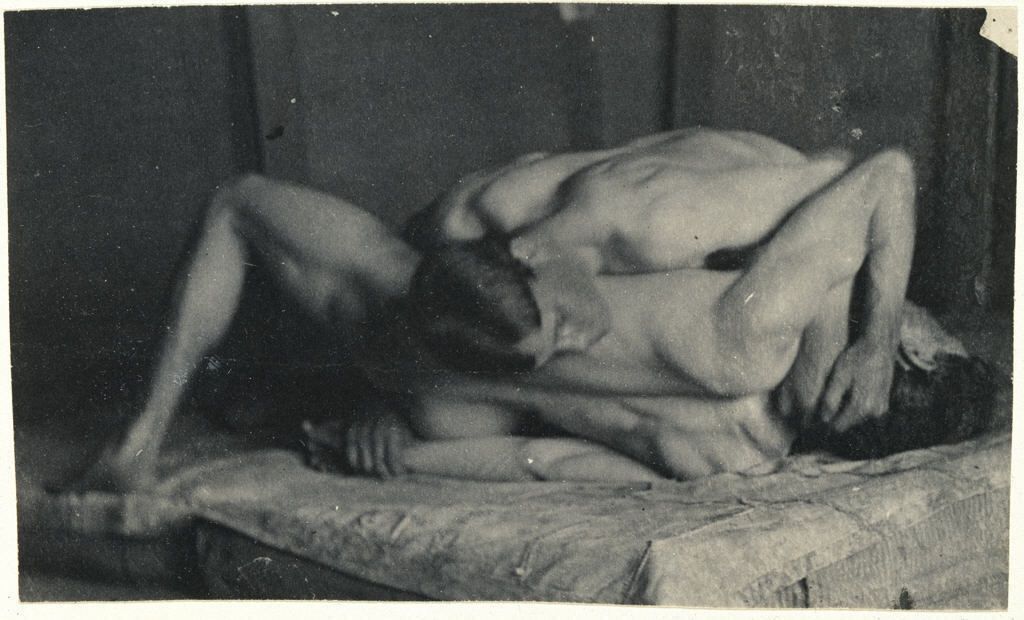

In May 1899, Eakins began Wrestlers by inviting two athletes to wrestle for him in his studio. Having decided on the pose—“the winning position, with a half nelson and crotch hold” as Cranmer described it—Eakins had the two men recreate it more formally and photographed them from the angle he would use in the final work. After a first version, left unfinished, Eakins produced a small compositional sketch, which was gifted to LACMA by William Preston Harrison, who first saw the work when it was exhibited in Los Angeles in 1927.

Eakins valued that wrestling required no special equipment, simply a combination of pliability and brute force from the male body. However, his wrestlers are not presented as particularly heroic, but instead maneuver themselves into a titillating position, their bodies intensely pressed against each other to create the optical illusion of a conjoined physique. His careful juxtapositions of clothed and unclothed figures, wrinkled and taut flesh, and the angles of the arms and legs suggest a studied artificiality. The finished work and its preparatory studies also reveal the artist’s extensive formal training: in the late 1860s, he had attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he studied with academic painters Jean-Léon Gérôme and Léon Bonnat.

In 1876, Eakins began teaching at his alma mater, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he introduced a new rigor into the curriculum of the country’s oldest art school. Increasingly, in both his painting and teaching, he concentrated on the male figure, finding ways to depict the male nude within contemporary and historical contexts. His deep conviction that the human being is the central concern of painting, and that the human being is composed equally of mind and body, had a profound and long-lasting influence on younger colleagues and later generations.

Wrestlers can also be interpreted as a spiritual self-portrait of a frustrated artist toward the end of his career. Although the focus on two nude figures underscores Eakins's academic training, which extolled and elevated the human body in its most perfect state, the unusual composition suggests that he intended the painting to be much more than a literal representation of the popular bourgeois spectator sport. In Eakins's best and most modern late paintings, he compelled the viewer to look and think again, often creating a feeling of discomfort. This was intentional as Eakins himself was in the midst of many personal, familial, and professional problems. He gave the final painting to the National Academy of Design as a diploma painting, satisfying a condition of his election as a member in 1902. The work thus stands as a testament to Eakins’s lifetime of teaching and painting, as he wrestled with the dilemmas of representation and embodiment.