Art at LACMA often inspires unexpected encounters, and one of the latest puts an Impressionist masterpiece right in your hands. In celebration of Collecting Impressionism at LACMA (on view through January 3, 2027), the LACMA Store collaborated with exhibition curator David Bardeen to create a functional object rooted in art history, transforming Camille Pissarro's Shepherds in the Fields with Rainbow (1885) into a handheld fan you can carry or display as a work of art in its own right. We spoke to Bardeen about the object, the piece that inspired it, and how adapting an artwork into something tactile can reshape the way audiences connect with art history.

Can you describe the artwork in the exhibition, Pissarro’s Shepherds in the Fields with Rainbow, that inspired the design of the fan?

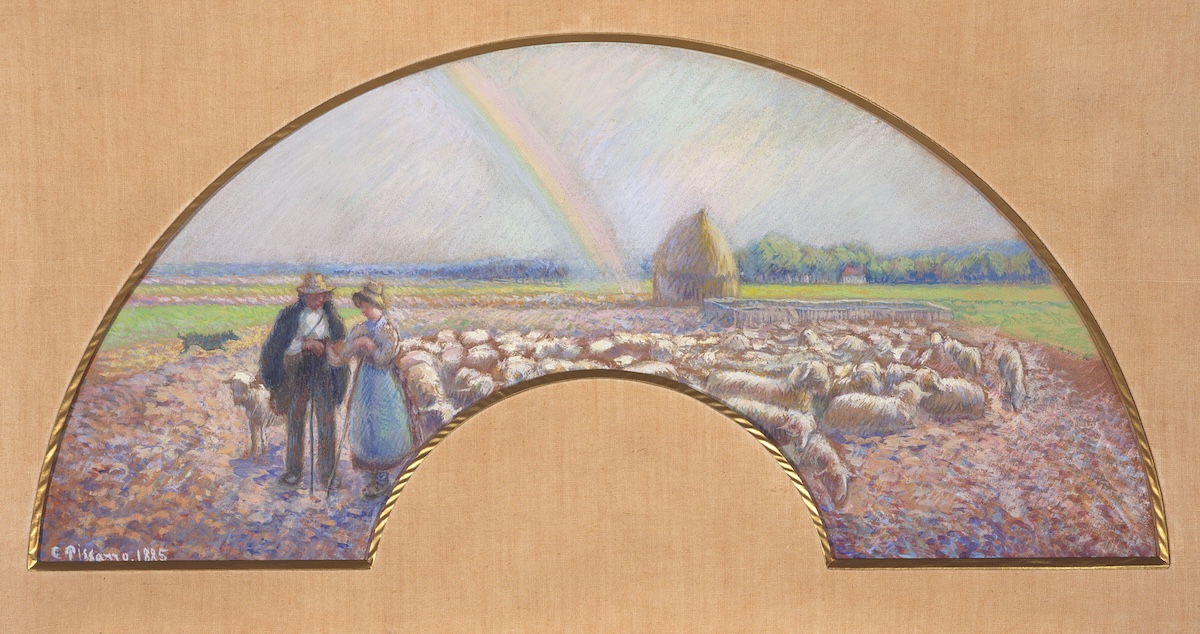

This really lovely work depicts a pair of shepherds (a man and a woman) tending to their sheep. The scene is the French countryside, and we can see green fields, a thatched hut, and a rainbow in the background which evokes the curved edge of the work itself. The scene is depicted with the Impressionists’ typically loose brushwork, capturing the atmospherics of a summer day and the way light reflects off surfaces. Among all of the works in Collecting Impressionism, it’s among my favorites because of the simplicity of the scene it depicts. The Impressionist painters grappled in many ways with the changes wrought by modern life in the late 19th century, and there’s a nostalgia to this picture, a look back to a simpler way of living.

What drew you to this particular piece as a source of inspiration for a functional object?

Transforming the work into a functional fan seemed like a great idea once we learned more about the history of the object. Like most visitors to the museum, I typically associate the Impressionist painters like Camille Pissarro with easel paintings, and typically in a square format. (The exhibition includes a number of other works by Pissarro, including his fabulous La place du Théâtre Français, a large oil painting with a dramatic aerial view of people bustling around Paris).

This picture of the shepherds is instantly intriguing because of its fan shape, and also the materials used. Pissarro created the scene with pastel and gouache (a water-based paint) rather than oil paint, and the support is silk rather than canvas. (For this reason, the work resides here at LACMA in the Department of Prints and Drawings rather than European Painting and Sculpture).

It turns out the fan-like shape of the work isn’t a coincidence; it hints at an aspect of Pissarro’s career, and of other Impressionist artists, that is perhaps lesser known to the general public: they experimented with many different media, including objects like silk fans. In this case Pissarro was inspired by Japanese fans that were on display at the Exposition Universelle (the World’s Fair) in Paris (held in 1867 and 1878), and this is one of a number of painted fans that he produced.

These fans may never have been used as fans; most of them were likely framed or otherwise displayed as decorative objects. But there’s something lovely about converting the work into an actual fan that LACMA visitors can use. In the scene of shepherds on the face of the fan, you can almost sense the heat of a summer afternoon, and a fan like this one comes in handy to cool things down.

How do you think transforming an artwork into a functional object changes the way audiences relate to it?

There’s something appealing about the opportunity to hold a work of art in the hand. We are all trained to look, but not touch, in the museum. Pissarro’s fan is a reminder that some works of art were meant to be touched, even if, in this case, we still can’t touch the real one in the exhibition. It’s also worth remembering that, for the most part, the Impressionist painters weren’t selling their works for millions of dollars back in the late 19th century. Their popularity, and the high dollar value that their works command, came later. (The cultivation of a taste for Impressionist artworks over many decades is one of the things Collecting Impressionism is about.) Back when Pissarro created this fan, he was struggling to make a living, so this experimentation with new media wasn’t just about creative innovation—he was also working to find an audience and a market. That’s a long way of saying that there was a commercial aspect to Pissarro’s work.

Why was a fan the right object for this interpretation?

Fans are fun and fascinating objects because of the way they bear images, the way they fold, the way they feel in your hand, and the way they create a stir in the world when used. In fact, fans are having a bit of a moment in the museum world right now. For those traveling to New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is having a show through May, Fanmania, which examines the production of fans in Europe and Asia in the 19th century. Fans are also flirtatious—you can use them to hide and reveal your face. Kids, who are naturally curious and love cool things, often love fans for all of these reasons, but we don’t see too many adults carrying them around. It would be fun if LACMA’s Pissarro fan created new fans for fans.