The restoration of Fritz Lang’s seminal expressionist film Metropolis (1927) recently got some of some of us thinking: how might this spectacular film and the equally iconic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (directed by Robert Wiene, released in 1920) relate to LACMA’s collection? These films defined respectively the genres of science fiction and horror, later brought to perfection in Los Angeles—along with film noir, which these films also influenced—but where did they come from?

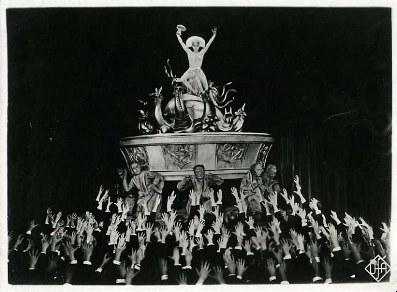

Horst von Harbou, Untitled (robot Maria dancing in night club), 1926, film still from Fritz Lang's movie Metropolis, purchased with funds provided by the Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation, Beverly Hills, CA

Working as a team of two curators (Britt Salvesen and myself), a curatorial fellow (Sienna Brown), and a curatorial assistant (Frauke Josenhans), we began combing through the thousands of works found together in the Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, Prints and Drawings Department and Photography Department and quickly found a myriad of connections as well as some surprises among works of art portraying madness, the experience of the city, the conditions of workers, attitudes toward women, and the role of orators in inciting social change, whether for good or evil. It was exciting for us to bring these objects together in the same room with projections of excerpts from these two great films in the exhibition Masterworks of Expressionist Cinema: Caligari and Metropolis. (This weekend the films will screen in full in the Bing Theater, along with Paul Leni’s Waxworks and F. W. Murnau’s Faust.)

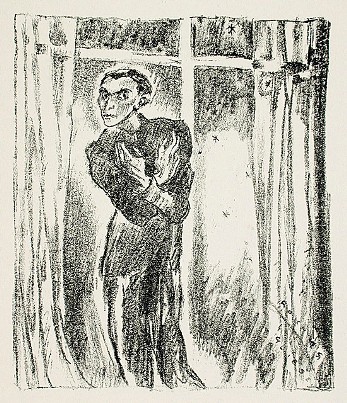

The Expressionists are known for exploring the "inner" mind, its complex feelings and psychological states. Yet they often conveyed this through setting and ambience. To do this they relied, in their paintings and graphics—as well as in the stage designs of the Expressionist theater—on the distortion of space and strong contrasts, whether in bold painted colors or starkly black-and-white graphics. This is what transforms a work like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s The Murder (1914) into a scene of pure horror. Printed in blood red and black, this huge lithograph portrays a disturbingly claustrophobic room closing in on railroad engineer Jacques Lantier, who suffers from hereditary madness and has just killed his lover Séverine, in a scene from Émile Zola’s La Bête Humaine. Dropping the knife, he falls back in horror.

Dr. Caligari set designer Hermann Warm understood films in a similar way, as “drawings brought to life.” He worked with two painters, Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig (who would also work on F. W. Murnau’s Faust, 1927), to craft a disorienting world of jagged forms, misshapen windows, tilting walls, and illogical shadows which were then lighted with extreme contrasts of light and shadow—in short, symbolic diagrams of psychological states through which actors move in entirely unconventional ways. All of this can be seen in amazing detail in several vintage Caligari set shots in our exhibition, in which the actors assume their roles in exaggerated poses. These photographs extend beyond the cropping of the actual film so you can actually see how the sets were built and painted.

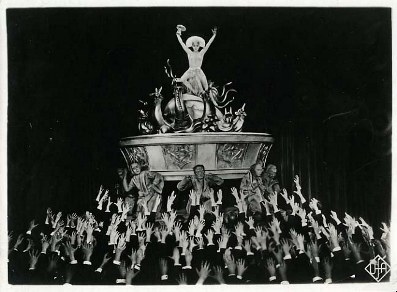

Unknown German Artist, Untitled (The somnambulist Cesare [Conrad Veidt]), 1919, set photograph from the film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The cabinet of Dr. Caligari), The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies

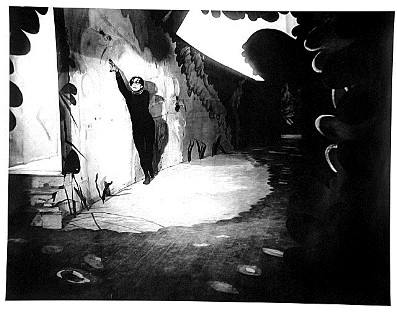

In one of these images we see Conrad Veidt as the somnambulist Cesare in Dr. Caligari creeping along the wall, more like a dancer than conventional actor, his knife hidden from our view, intending to commit his next murder. This acting style comes right out of the Expressionist theater, which rejected verisimilitude and relied on exaggerated emotions and gestures that were more operatic than natural. Veidt, who also starred in Paul Leni’s 1924 Waxworks, was certainly indebted to the first and greatest expressionist stage actor, Ernst Deutsch, who was hugely successful in the first full-length Expressionist play, Walter Hasenclever’s The Son, as portrayed in a lithograph by Rochus Gleise, who would be Art Director for Murnau’s Sunrise (1927), Production Designer for Paul Wegener’s The Golem, and Assistant Director for Caligari. And here we have some of the talent that made film noir possible later on in Hollywood—Deutsch playing Baron Kurtz in The Third Man (1949)and Veidt playing Major Heinrich Strasser in Casablanca(1942).

Rochus Gliese, "Der Sohn" von Walter Hasenclever 1 ("The son" by Walter Hasenclever 1), 1918, from the portfolio Das junge Deutschland: Phantasien über Aufführungen des Jahrs 1917/18 (The Young Germany: Fantasies about shows of the years 1917–1918), The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, purchased with funds provided by Anna Bing Arnold, Museum Associates Acquisition Fund, and deaccession funds

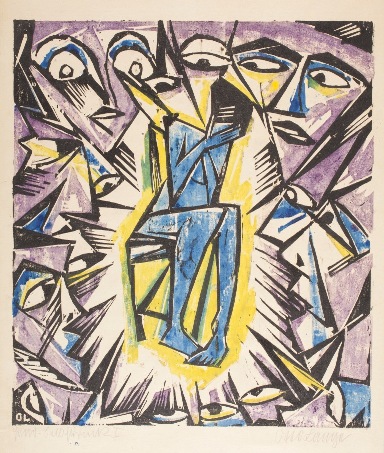

It is perhaps film noir that comes to mind when we see the decadent nightlife portrayed in Metropolis (remembering that Fritz Lang would direct The Big Heat in 1953). In one scene, the screen fills with hands and then close-ups of dozens of eyes conveying the intense male gaze in a nightclub where the robot Maria dances as a femme fatale. We find a parallel in Otto Lange’s Vision, a color woodcut from around 1919, only here an overpowered female figure covers her face and crouches on a chair at the center of the composition, the intensely staring eyes being part of her own hallucinatory vision.

Otto Lange, Vision, probably after 1919, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies

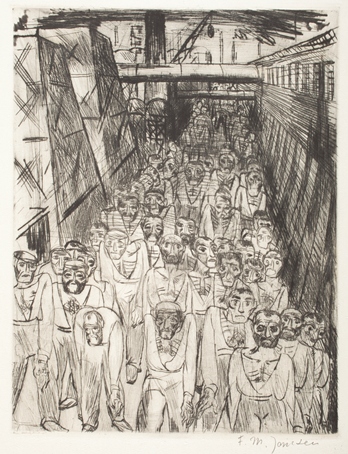

But the most stunning aspect of Metropolis is its set designs by Erich Kettelhut, inspired by Lang’s first glimpse of New York City’s skyline, suggested in our exhibition in photographs by William Rittase and Karl Struss from the teens and twenties. The film presents two worlds: the workers’ oppressive underground realm of machines and tenements, and the futuristic paradise above of skyscrapers, parks, and sports arenas for the leisure classes. Two etchings from Franz Maria Jansen’s 1921 portfolio Industry capture a dehumanizing urban landscape of factories billowing smoke and cavernous rows of machines through which workers trudge mechanically, very much as they are portrayed returning from work in Metropolis.

Franz Maria Jansen, Untitled, 1921, from the portfolio Industrie (Industry), The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, purchased with funds provided by Anna Bing Arnold, Museum Associates Acquisition Fund, and deaccession funds

The bustling metropolis from the future portrayed in the film was certainly based in part on Berlin, one of the fastest-growing and most modern cities in Europe at the time. Fleeting impressions of buildings, advertising signs, elevated railways, traffic, and noise are all captured in Otto Möller’s Berlin Expression, a lithograph from around 1920. But perhaps the most inspiring icon for artists of the time was the cathedral, whether conveyed in crystalline light, as in Max Thalmann’s woodcut, or conflated with urban skyscrapers, as seen in New York's Metropolitan Life Tower photographed by Karl Struss and in William Rittase’s So This is New York, or as a unifying symbol of the future, exemplified in Lyonel Feininger’s woodcut, Cathedral, accompanying Walter Gropius’ founding Bauhaus manifesto of 1919. All these symbols come together—crystalline light, soaring towers, elevated bridges, and an ominous vision of the future—in Heinz Schulz-Neudamm’s stunning gold-hued poster for Metropolis. By this you will be convinced that the film is worth the price of admission!

William Rittase, So This is New York, c. 1927, Los Angeles County Fund

Timothy Benson, Curator, Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies