Opening November 1 (members can see it now), Stanley Kubrick is the first major retrospective in the United States of the notoriously scrupulous filmmaker’s work. Featuring annotated scripts, production photography, lenses, costumes, and props, exhibition spans the breadth of Kubrick’s practice and offers viewers insight into the uncompromising vision of one of cinema’s greatest directors. Film Independent at LACMA curator Elvis Mitchell reflects on Stanley Kubrick as filmmaker, photographer, and myth.

I may be alone in this, but I think of Stanley Kubrick as an editor. Probably no one who has ever watched Barry Lyndon or The Shining or Eyes Wide Shut can read that sentence with a straight face. But to me, Kubrick was an editor in part because most of his films were adapted from other sources, from which he then mercilessly sliced away material that didn’t lend itself to the motion picture medium.

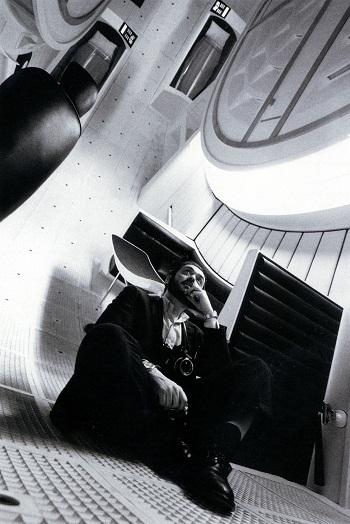

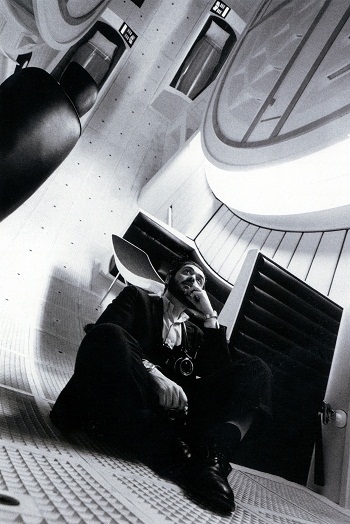

Stanley Kubrick in the interior of the space ship Discovery, 2001: A Space Odyssey, directed by Stanley Kubrick, 1965–68, GB/United States, © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

I primarily think of Kubrick as an editor, however, because he was also a photographer, and the best photographers—from Mary Ellen Mark to James Van Der Zee to Robert Capa—are artists who function both as directors and cutters: each shot is basically an entire movie tailored into a single frame. For me, then, Kubrick is first and foremost a photographer, like them, and almost any still from his monochromatic movies tells a complete story. That’s what comes to mind when I see Kubrick’s black-and-white films: they’re “pictures” in both senses of the word (think of how Martin Scorsese, who acknowledges Kubrick as a de facto mentor, uses the directing credit “A Martin Scorsese Picture”). They have the finesse of a finely honed visual presentation but also the head over heels tumble that a moving picture provides.

I find that I have a special affinity for Stanley Kubrick’s black-and-white films. There’s an unspoken carnality to them, possibly because they have the silvery shimmer of gelatin prints, luminescent and hot, and the actors give off a satiny glow that’s less painterly and far more vivid than in Kubrick’s color work. The luscious women, in particular, all of whom suggest cigarette girls or dancers, have a comprehension of their power that’s almost precognitive. You can easily go from one of the young women in Kubrick’s early photographs for Look magazine, which helped establish his name, to Sue Lyons’s simmering performance as the title character in Lolita—it’s a natural progression.

Matthew Modine as Private Joker in Full Metal Jacket (still), directed by Stanley Kubrick, 1987, GB/United States, © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Part of that carnality comes from Kubrick’s undeniable love of the photochemical process. He treated emulsion as a character. (Nowhere is that passion for the tactile qualities of film more evident than in Full Metal Jacket, where you can almost read the emulsion in the print.) His feel for photo stocks led Kubrick to treat them as if he were searching for just the right ensemble to clothe his actors. As a result, the actors in his black-and-white features never seem as languid as they sometimes appear in his color films. In Full Metal Jacket, for example, after the Marines are browbeaten into a pack of grunts during the boot-camp prologue, Kubrick leeches the color from the film. The rest of the movie takes on a heady quality, as the soldiers wander through a Southeast Asia that looks more like Sheffield with palm trees than the jungles of Hué—a dislocated drift owing in part to Kubrick’s refusal to shoot in Asian locations.

All of Kubrick’s color films have the same trippy, distended quality, in which every minute seems to last ninety seconds. (No wonder so much of the 2001: A Space Odyssey fandom ran their tongues across acres of acid before diving into the film during its original 1968 theatrical release.) We wallow in Kubrick’s disregard for time as it weighs on the perquisites of story; minutes cease to matter as the protagonists are tossed about from one disaster to another. In The Shining, especially, Kubrick has no use for the temporal world. We enter the Land that Time Forgot—not in the standard When-Dinosaurs-Walked-the-Earth fashion, but a Time that simply neglected to include the happenings at the Overlook Hotel.

Lobby of the space station in 2001: A Space Odyssey (still), directed by Stanley Kubrick, 1965–68, GB/United States, © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

The stubbornness required of a filmmaker when he moves into the manufacturing of epics often makes him lose track of time. Intent on expanding scale, he instead sacrifices the clarity that keeping a film compact demands, and the bloat blurs the film’s aim. For Kubrick, it’s an entirely different thing. He may have been the only director who turned to making bigger movies without losing the over-deliberate acuity of his meticulously worked smaller films. With the color films, that obsession led him into another dimension, since he seemed to feel a need to overcompensate. One reason is that he didn’t deepen the emotional spectrum of his longer, color works. Often, when a director capable of superlative emotional intimacy literally changes the size of the screen, he wants us to see all of the cinematic brushstrokes he never had the money to provide. He’s as overwhelmed as we are in his effort to show every inch the camera travels on the tracks—so much so that we begin to wonder if the cinematographer was being paid by the mile. That never happens with Kubrick; we’re simply aware that time is another element at his disposal. There’s not a single frame that escapes his attention.

In Kubrick’s black-and-white movies—what connects them to his early magazine photography, in fact—the opposite holds true: The director’s artistic confidence registers as a full-tilt sprint. How we perceive time is the line of demarcation that separates the color films from the express-train alacrity of the black-and-whites. There’s not a heartbeat to lose when color isn’t a consideration.

In Lolita, Kubrick’s initial descent into the adolescent sexual obsession that underlies so much of Eyes Wide Shut time is indeed of the essence. Humbert Humbert, played with a masterly succumbing-to-vanity by James Mason, has to act on his churlish hunger for the object of his desire before she becomes . . . well, a woman. And that’s where the awful comedy comes from: Humbert’s comprehension of how horrible his plan is, and then his following through on it anyway. But Humbert’s pride is at stake, and for the characters in Kubrick’s black-and-white films pride is an Old Testament deficit that invariably goeth before destruction.

Sue Lyon as Dolores “Lolita” Haze, Lolita, directed by Stanley Kubrick, 1960–62, GB/United States, © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., photo by Bert Stern

That same pride, however, is part of the compact Kubrick made with the subjects of his Look magazine photographs. Each real-life model radiates it, and Kubrick’s appreciation of that quality—it’s the kinship he shares with them—makes it impossible for him to turn the tables on them, as he generally did with his film protagonists. He shows the instincts of an artist in those pictures by surrendering himself to something bigger than he could possibly contain. Stars in their own right, the models took authorship of their lives in his pictures. Kubrick obviously admired their poise, the way they controlled the moment, but it’s the sense we get of partaking in their pleasure that adds a note of voluptuousness to the work.

The even-tempered calculation in Kubrick’s early photographs is shattering for one so young. He was effectively converting single images into short films of overwhelming emotional sophistication: visual poetry that resonates because of what we don’t see. The careful handling Kubrick gave to the subjects in those photos—or, rather, his inability to achieve the same effects—could be what led him to scuttle his debut feature film, Fear and Desire, whose anxious, slightly jittery qualities are nowhere to be found in the perfectly realized noirs Kubrick would later make, in which every narrative dart is launched hard into the films’ bull’s-eyes. The same can be said of the street photographs, with their imagined, unspoken dialogues, where each nuance in each face feels pulled from some larger schematic in Kubrick’s head, evidence of lurid, sweaty secrets. The still images have a terse vivacity that Kubrick discovered how to realize in movies only with The Killers and Killer’s Kiss.

Stanley Kubrick and Jack Nicholson on the set of The Shining, directed by Stanley Kubrick, 1980, GB/United States, © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

When I first saw The Usual Suspects, it suddenly hit me who the real Keyser Söze was: Stanley Kubrick. A figure enveloped in mystery and carefully constructed anecdote, someone about whom everyone has a different story, but all of which end in submission. There is probably no other American filmmaker of his generation who so thoroughly dramatized cruelty, and Kubrick’s whims—his playful malice—have become an integral part of his legend.

Like Söze, the near mythical ur-gangster at the heart of The Usual Suspects, Kubrick was a master manipulator who could bend people to his will and then place them exactly where he wanted them. When it is said in the film that Söze was the one to gather a group of extras and march them into certain death, I was reminded of Kubrick’s ability to extract the ultimate commitment from his collaborators. He was one of the last working directors to exist, like Söze, as a living myth

Stanley Kubrick during the filming of 2001: A Space Odyssey, directed by Stanley Kubrick, 1965–68, GB/United States, © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Kubrick’s sly willfulness, his willingness to use actors as objects, brings to mind the bastardization of Baudelaire that Verbal Kint, the limping petty criminal played to perfection by Kevin Spacey, carefully intones about Söze, his alter ego: “The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.” People tend to speak about Stanley Kubrick in such rapt terms, even as he exploited them for his own artistic gains. In Kubrick, screenwriter Michael Herr’s memoir about his psychological tour of duty with the director, he writes, “When I met him in 1980, I was not just a subscriber to the Stanley Legend, I was frankly susceptible to it.” In other words, Herr entered a working relationship with Kubrick with eyes wide shut. Kubrick ended their first, lengthy phone conversation with, “Oh, and Michael . . . do me a favor, will you? . . . Don’t tell anybody what we’ve been talking about.” You can almost hear the nervous chuckle from Herr as he hangs up the phone, realizing that he’s just happily extended a femur into Kubrick’s snare. A few years of such phone conversations passed before Herr started working with the director on what became the screenplay of Full Metal Jacket. “By then,” Herr later remarked, “I knew I’d been working for Stanley the moment I met him.”

Elvis Mitchell, Curator, Film Independent at LACMA