LACMA, in many ways, bears the flags of hundreds of nations, for we keep the treasures of many beloved cultures. Many who walk through our galleries are proud that their culture is present. So in Lost Line: Contemporary Art from the Collection, a stunning exhibition, which closes this Sunday, February 24, in which landscape—a fundamental visual construct—has been re-envisioned and put in new contextual dimensions, a sort of reframing. It is not merely a nineteenth-century Thomas Cole painting or Frederic Edwin Church’s wonder of an American Eden, which are beautifully displayed in Compass for Surveyors on the third level of the Arts of the Americas Building.

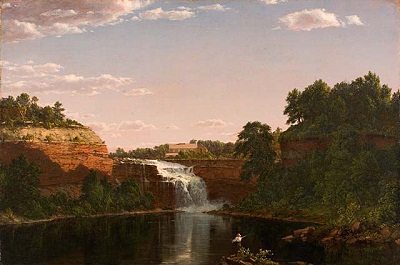

Frederic Edwin Church, Lower Falls, Rochester, 1849, signed and dated lower left: F.E. CHURCH 1849, gift of Charles C. and Elma Ralphs Shoemaker

Frederic Edwin Church, Lower Falls, Rochester, 1849, signed and dated lower left: F.E. CHURCH 1849, gift of Charles C. and Elma Ralphs Shoemaker

But the whole experience of our modern world is thrown into hard, fragmentary, fascinating relief. Here the contemporary “-isms” are not in some evolutionary steps toward an unknown apex. Instead, they are seen through their separate perceptions with a central thematic conceptual idea. Artists across generations, such as Buckminster Fuller, Robert Smithson, Erin Shirreff, Gabriel Orozco, and many more, dynamically re-imagine the complex contemporary view of our world as representations that filter through maps, paintings, sculptures, including land art as conceptual projections devising different ways and photography as metaphor that questions our role in nature.

Installation view, Lost Line: Contemporary Art from the Collection, November 15, 2012–February 24, 2013, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Installation view, Lost Line: Contemporary Art from the Collection, November 15, 2012–February 24, 2013, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Viewing these works is like passing through the landscape with new eyes and experiencing multifaceted forms in which the unexpected lies in wait. This is more of an investigation into an aesthetic range, from monuments to concrete urban constructs, from the beauty of dirt to abstract painting, from enhanced realism to collage and video—not mere idealization but a brute realism with refined ulterior aspects. We are made to sense a more complex existence.

Installation view, Lost Line: Contemporary Art from the Collection, November 15, 2012–February 24, 2013, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Installation view, Lost Line: Contemporary Art from the Collection, November 15, 2012–February 24, 2013, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

But, of course, such an art can hold unexpected surprises, as I was to find out. And that such a moment would produce a shock and a tonic of sheer sentimentally vibrant emotion was indeed a wonder. The arena of the sentimental, the characteristics of which have been alienated in our super-cool cultural self-image, can play as an impulse on one’s most simplistic notions of national brotherhood and national identity. A gated no-man’s-land for the so-called serious instinct suddenly surrenders to our base feelings.

Steve, McQueen,Static (still), 2009, 35mm film transferred to HD video,gift of Steve Tisch, © 2012 Steve McQueen

Steve, McQueen,Static (still), 2009, 35mm film transferred to HD video,gift of Steve Tisch, © 2012 Steve McQueen

So there I was in the midst of an unrealized seduction, while a video by the British artist Steve McQueen called Static wove its (white) magic on the simplest of terms. At first, the piece didn’t seem particularly unique or even daring. It even seemed to have some of Bruce Nauman’s ironic ordinariness, which could so often lead to a dead end. While I was watching Static, time slipped a beat, and I could say I was kind of dizzy, or better, mesmerized. The Statue of Liberty was in motion. She seemed to move through the hazy populated landscape, passing over the plated silver of the water, and backgrounded by the checkerboard geometry of glass-wall buildings. Black boats were caught in the glow of a hidden sun on the distant horizon. Lady Liberty seems to see and hear everything that we do—the aberrant sound of a helicopter—a voice, so to speak—injected into those regrettable wars and their movies, both real and surreal. They are our nightmare sounds, our dumb call to battle— “. . . the smell of napalm in the morning” —those crazy blades cutting the air, slicing memories up. And then there is beautiful silence as she twirls me back to some giant American meaning—perhaps something heroic in spite of it all was grand and sad.

My chest swelled in a counterclockwise motion, and I felt the distinct jab of a patriotic moment. I was nearly hypnotized by this monumental American icon, by the jerking, jittery gold flame erratically shifting up and down.

Hylan Booker

Lost Line: Contemporary Art from the Collection is on view through Sunday, February 24, in BCAM. Members see this exhibition and all others for free.