LACMA’s permanent collection installation, Compass for Surveyors: Nineteenth-Century American Landscapes, gives visitors a chance to see old favorites in a new context, and to see some paintings (and photographs) that either have not been seen before, or have not been on display for several years. LACMA’s Director of Adult Programs, Mary Lenihan, who trained originally as an American art historian, offers this commentary on the gallery, which will be featured in her Point-of-View gallery talk on Thursday, at 12:30 pm.

My first position at LACMA, in 1991, entailed assisting curator Ilene Susan Fort in the American Art curatorial department, so I had a great introduction to the paintings now on view, and many of the landscapes became my LACMA favorites. American photography has been an interest of mine, as well, since the medium, introduced to America in 1839, literally grew up with the nation. So the whole idea of Compass for Surveyors is fascinating.

The George Inness painting, October, from the 1880s, is an example of how American landscape painters absorbed earlier approaches and then came to a singular mature style. Inness began early in his career in what was called the Hudson River School landscape tradition – named for the pre-Civil War painters, who were not formally organized, that painted the grandeur of the newly discovered American landscape with painstaking attention to detail. Inness later spent a great deal of time in Rome as well as in France, and developed from traditions he found there a preoccupation with painting outdoors, emphasizing light and atmosphere. He combined those interests with his deep Swedenborgian faith, a theology that suggests nature’s correspondence with spiritual values. Inness’s later landscapes, including October, often include scenes of nature in twilight or in a soft focus that nearly de-materializes the setting. We do not know the religious significance of such scenes, but the artist’s interest in spiritual concerns did not preclude careful planning. A close look at October reveals meticulous attention to composition, as the gap in the trees and its reflection in the pond are situated at the exact center of the canvas.

Autumn Morning on the Potomac, William Louis Sonntag, United States, circa 1860s, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Yolande B. Markson

Autumn Morning on the Potomac, William Louis Sonntag, United States, circa 1860s, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Yolande B. Markson

William Sonntag’s Autumn Morning on the Potomac has not been on view recently. We do not know much about the artist, nor much about the painting, for that matter. But it fits well into the Compass for Surveyors installation by reminding us of the geographic breadth of American landscape painters. If the Hudson River painters were known for their work depicting the Hudson River Valley and New England scenes, some chose different parts of the country as subject matter. Sonntag, born in Pennsylvania, grew up in Cincinnati, and while he eventually settled in New York, he continued to visit the Ohio River valley and made many sketching trips. Among those was an 1860 trip to Virginia, which probably was the inspiration for this canvas. Painted with careful attention to detail, it seems to capture a specific scene. The location and the date of the painting are of interest historically, as abolitionist John Brown’s famous raid on Harper’s Ferry, along the Potomac, would have just occurred, and the bitter sectionalism that would pitch the country into Civil War was already widespread. The painting shows no sign of this, however, instead celebrating the picturesque and rural American landscape.

Thomas Hill’s Emerald Bay, Lake Tahoe, from 1864, has often been on view, and in the context of Compass for Surveyors, is hung on a wall with only a few Western landscape paintings, facing the two dozen or so Eastern scenes on the opposite wall. This painting beautifully captures the spirit of LACMA’s relatively few paintings of Western scenes from the mid-19th century: a presentation of the awesome beauty of the mountains, complete with waterfall and snow-capped peaks, untouched by human domestication. This was the land of gold rushes, of infinite opportunity, and sublime natural wonders. Hill made his living in San Francisco, but he started as a painter in the Hudson River Landscape tradition in New Hampshire. His westward move thus paralleled the westward move of Easterners, and other artists, too. The figures to the left of the painting offer a perhaps startling note; the visitors are well dressed, likely preparing for a picnic as the woman seems to signal a companion in the boat to the right. These are tourists, out for a day trip to a scenic spot. As early as the 1860s, the West—and California—was already important as a tourist destination.

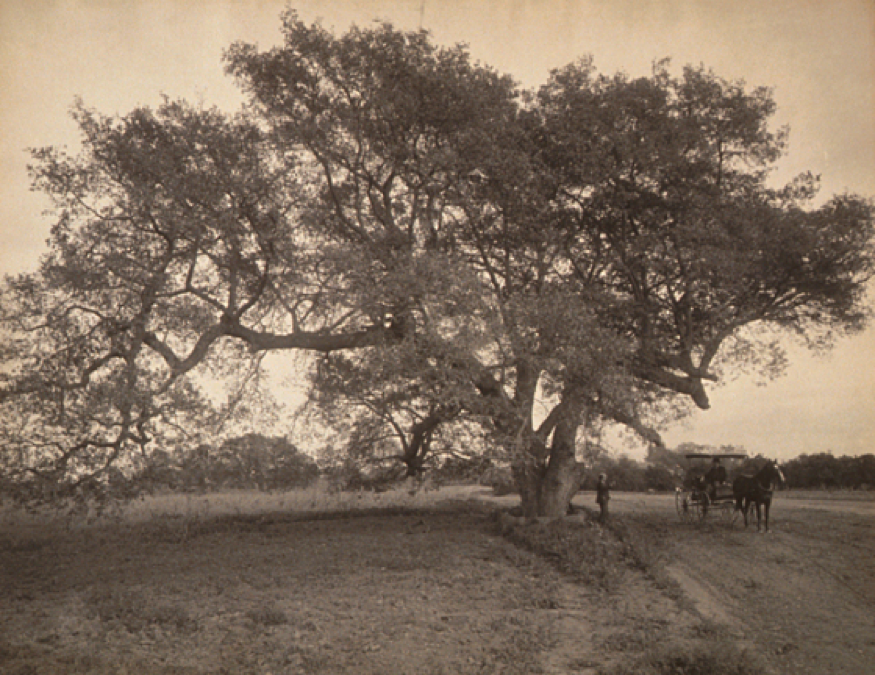

Oak Grove Near Pasadena, California, William Henry Jackson, United States, circa 1900, Ralph M. Parsons Fund

Oak Grove Near Pasadena, California, William Henry Jackson, United States, circa 1900, Ralph M. Parsons Fund

A photograph that is of local interest here in Los Angeles is William Henry Jackson’s Oak Grove Near Pasadena, California, from around 1900. Jackson was, by this time, a famous and celebrated photographer; he had accompanied some of the early surveying parties that roamed the American West following the Civil War, documenting such locations as the Grand Tetons and the area that later became Yellowstone National Park. This shot is notable for its universality; the location could be almost anywhere in the United States. The composition is clearly the work of a master, but for us here in Southern California, it is a reminder that until a bit later in the last century, our region was largely unsettled and rural. The horse-drawn wagon and unpaved road seem light years away from the freeways and densely settled neighborhoods of today.

Compass for Surveyors offers many opportunities for museum visitors to see something new, and to see something familiar presented in a new way. The compass in the middle of the gallery is a metaphor; just as it can point in any direction, viewers can find multiple viewpoints and meanings as they look around the room. Meet at 12:30 pm in the BP Grand Entrance, by the doors to the Ahmanson Building, on Thursday, April 4, if you are interested in hearing more about these and other works of art currently on display.