FiFo. No, this is neither the name of a new restaurant nor that of an energy drink, but the abbreviation for Film und Foto (Film and Photography), a 1929 landmark exhibition on modern art, which inspired a gallery in the exhibition Hans Richter: Encounters, on view through Monday, September 2, in the Resnick Pavilion at LACMA.

Hans Richter Encounters, in the Resnick Pavilion at LACMA, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Hans Richter Encounters, in the Resnick Pavilion at LACMA, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

FiFo, which opened in Stuttgart and travelled to Berlin and other cities, connected film and photography in unprecedented ways. This exhibition showcased the diversity of contemporary developments in these media, as well as their use in design, advertising, and other forms of mass communication. The show also presented an extraordinary range of international photographers and filmmakers, including participants from the United States, the Netherlands, the Soviet Union, France, and Switzerland.

Anton Bruehl, Still Life–Silver, c. 1930, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © 2013 Anton Bruehl Estate, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Anton Bruehl, Still Life–Silver, c. 1930, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © 2013 Anton Bruehl Estate, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

As curator of the film section of FiFo, artist and filmmaker Hans Richter was strongly involved in the exhibition. By 1929, Richter had pioneered abstract film with his Rhythm 21 and Rhythm 23, which were among the works of this genre created. Richter fought for film to be recognized as a legitimate art form. FiFo emphasized the role of film in modern art and society, and Richter’s selection aimed to showcase an international spectrum of new developments in the medium. Among the innovative filmmakers he included were Charlie Chaplin, Alexander Dovzhenko, Marcel Duchamp, Viking Eggeling, Fernand Léger, Man Ray, Germaine Dulac, and Walter Ruttmann.

Room with works by László Moholy-Nagy at the 1929 FiFo exhibition in Berlin.

Room with works by László Moholy-Nagy at the 1929 FiFo exhibition in Berlin.

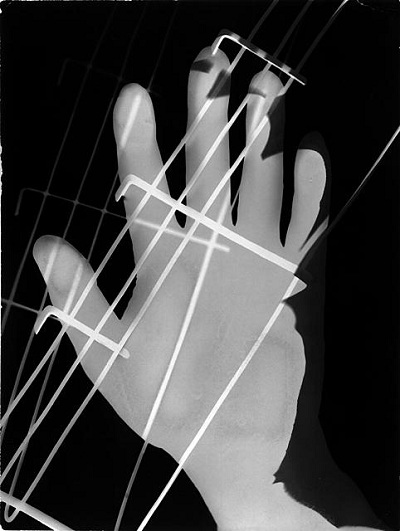

László Moholy-Nagy, Untitled, c. 1925, Ralph M. Parsons Fund, © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

László Moholy-Nagy, Untitled, c. 1925, Ralph M. Parsons Fund, © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

As for the photography component of the exhibition, the FiFo planning committee invited Hungarian designer and photographer László Moholy-Nagy to organize a selection of photographs that would lend a historical continuum to the exhibition. He also contributed a number of his own works. Moholy-Nagy experimented in his work with different techniques, radical spatial perspectives, and was a pioneer of photograms and photomontage. FiFo presented numerous representatives of the New Vision movement, an avant-garde approach to photography that sought to present an entirely new way of seeing the world. Several New Vision photographers were students or teachers at the Bauhaus, the highly influential German design school.

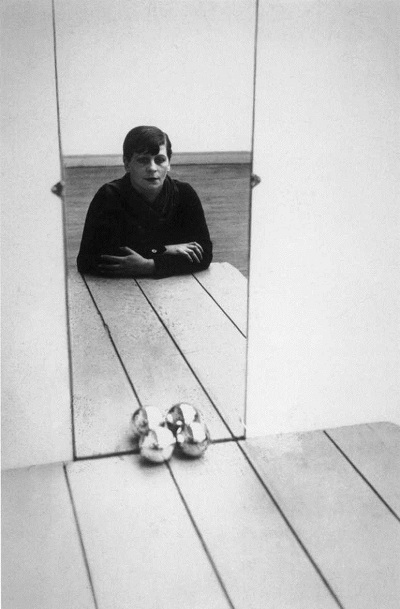

Florence Henri, Self-Portrait, 1928 (printed 1974), the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © 2013 Florence Henri Estate, Galeria Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa, Italy, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Florence Henri, Self-Portrait, 1928 (printed 1974), the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © 2013 Florence Henri Estate, Galeria Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa, Italy, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

![[Image 7] Edward Weston, No. 11 Cypress—Point Lobos (The Flame), 1929, Gelatin silver print, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection. Gift of The Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin © 2013 Arizona Board of Regents, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA](/sites/default/files/attachments/10.jpg) Edward Weston, No. 11 Cypress—Point Lobos (The Flame), 1929, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © 2013 Arizona Board of Regents, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Edward Weston, No. 11 Cypress—Point Lobos (The Flame), 1929, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © 2013 Arizona Board of Regents, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Edward Weston and Edward Steichen were in charge of the selection of American photographers for FiFo. Weston was representative of the new formalist approach, which emphasized photography’s compositional elements as it was then developing in the United States, particularly on the West Coast. Imogen Cunningham, another American photographer, followed a similar method in her botanical images examining flowers as studies in form.

![[Image 8] The Russian Room, designed by El Lissitzky, at the 1929 FiFo exhibition in Stuttgart.](/sites/default/files/attachments/6_1.jpg) The Russian Room, designed by El Lissitzky, at the 1929 FiFo exhibition in Stuttgart.

The Russian Room, designed by El Lissitzky, at the 1929 FiFo exhibition in Stuttgart.

Another particular aspect of the exhibition was its innovative design: El Lissitzky, one of the leading Russian Constructivists, was commissioned (along with his wife, Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers) to create the exhibition space for the selection of Russian photographers at FiFo. The Russian Room differed from the other galleries: it featured highly original gallery architecture and was the only section that directly integrated film and photography, showing extracts of films by contemporary Russian filmmakers alongside photographs.

![[Image 9] Hans Richter Encounters, LACMA, Resnick Pavilion, Photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA](/sites/default/files/attachments/2_5.jpg) Hans Richter Encounters, in the Resnick Pavilion at LACMA, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Hans Richter Encounters, in the Resnick Pavilion at LACMA, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Hans Richter: Encounters gives a glimpse of this landmark exhibition by displaying photographs by Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy, and Edward Weston, as well as by several members of the New Vision photography, such as Hans Finsler, Albert Renger-Patzsch, and Florence Henri. We were inspired by the original display of art in the 1929 FiFo exhibition and took the challenge not to recreate it, but to convey the spirit of it. Excerpts of films selected by Richter for FiFo are also shown in the same gallery.

![[Image 10] Hans Richter Encounters, LACMA, Resnick Pavilion, Photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA](/sites/default/files/attachments/3_7.jpg) Hans Richter Encounters, in the Resnick Pavilion at LACMA, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

Hans Richter Encounters, in the Resnick Pavilion at LACMA, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA

If you want to experience FiFo in a 21st-century dimension, check out the augmented-reality app, developed by artists John Craig Freeman and Will Pappenheimer especially for our show. (View them through one of the iPads available in the gallery.) LACMA’s Amy Heibel wrote about this app here and also interviewed the two artists. Starting from an installation shot of The Russian Room, they combined virtual and interactive space with excerpts of Russian films shown at at the original FiFo, including Dziga Vertov’s Kino Eye and Man with a Movie Camera and Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. Both artists completely immersed themselves in Richter’s universe, using signature elements of some of Richter’s own films such as Ghosts before Breakfast—watch out for the flying hat!

Richter would have loved it. Whether you are a film or a photo fan, you should come see FiFo and pay homage to one of the landmark exhibitions of the 20th century.

Frauke Josenhans

Curatorial Assistant, Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionists Studies