Every picture tells a story, as we all know. But with artworks the history of a picture’s journey through time also tells an important story. Where a picture has been, who its various owners were, and where it has been exhibited and published all reveal something about how it was valued, and how it was interpreted—that is to say, what the painting meant, even “said,” to those who experienced it in the past. The history of an object’s ownership is called its provenance, from the French word provenir, which means "to come from."

The Nazi era in Germany (1933–1945) culminated in genocide and extraordinarily egregious violations of cultural norms, and a concerted effort has been made in recent decades among museums around the world to focus special attention on this era in assessing provenance. Few public museums in the United States have devoted more sustained attention to modern German art and the cultural destruction wrought by the Nazi regime than LACMA. We have a history of presenting groundbreaking exhibitions on modern German art, particularly “Degenerate Art”: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany (1991), the first major exhibition to explore the attack mounted by the National Socialists against modern art and artists; and Exiles + Emigrés: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler (1997), which traced the migration of artists within Europe and to the United States. Both exhibitions were prepared by extensive research conducted by teams of experts and was accompanied by engaging public programming. LACMA has also presented exhibitions on many of the artists designated as “degenerate” and persecuted, including German Expressionist Sculpture (1983); German Expressionism, 1915–1925: The Second Generation (1988); The Apocalyptic Landscapes of Ludwig Meidner (1989); Nolde: The Painter's Prints (1995); and most recently Hans Richter: Encounters (2013), as well as more than 50 exhibitions organized by the Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies. You can read in full the catalogues to some of these exhibitions and others in LACMA’s online Reading Room. Projects by other institutions in Los Angeles include the Getty Research Institute’s Provenance Index® databases as well as its ongoing acquisition of Holocaust-Era Research Resources.

These projects and similar endeavors in German museums, as well as a growing and already vast scholarly literature on the subject of Nazi cultural policies, provide not only a picture of cultural destruction and looting on an almost unimaginable scale, but an understanding of the roles of those who must be held accountable. Additionally, these projects shed light on the moral complexities faced by art dealers, museum officials, journalists, and even artists themselves as they saw what was once a highly cultivated world of culture disintegrating around them.

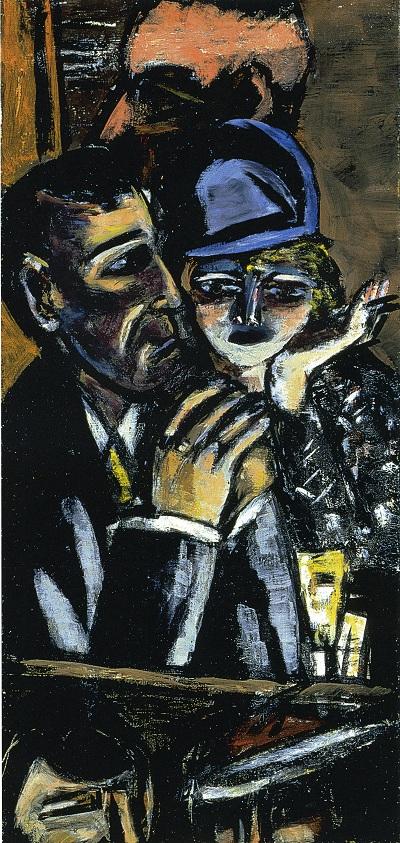

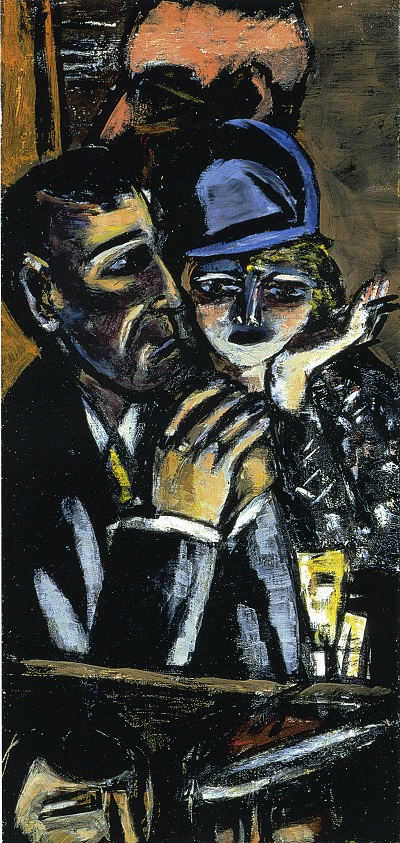

Max Beckmann, Bar, Brown, 1944, gift of Robert and Mary M. Looker, © Max Beckmann Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn

Max Beckmann, Bar, Brown, 1944, gift of Robert and Mary M. Looker, © Max Beckmann Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn

LACMA was recently gifted a painting whose provenance is instructive in understanding the complexities of this tragic era. Like thousands of paintings now hanging in public museums and private collections, Max Beckmann’s Bar, Brown (1944), previously discussed on Unframed, passed through the hands of at least one art dealer who catered to the Nazi regime. These art dealers generally had two lines of business with the Nazis: disposing of modern art designated by the Nazis as “degenerate” in return for hard currency abroad, and providing traditional art of all periods to the Nazi elite, and especially to Hitler’s huge museum project planned for city of Linz. It has been documented by the Art Looting Investigation Unit that some 68 dealers in Germany alone sought works for this massive museum. Holland, where Beckmann sought refuge in 1937 upon hearing Hitler’s tirade at the opening of the Entartete Kunst (“Degenerate Art”) exhibition, became under German occupation one of the busiest and hottest markets for traditional art—and especially old master works—so much so that prices on the Dutch art market were artificially inflated.

Yet Jewish families, collectors, and dealers were not able to benefit from this situation. They fled Holland and were forced to sell at ludicrously low prices, or worse, were transported to concentration camps to face certain death, while dealers were given license to loot the collections they left behind. In about 1937 the Nazis commissioned a select group of dealers (slightly more than a half a dozen), principally renowned firms, to dispose of “degenerate art" purged from state collections. The most visible event was an auction in 1939 of 125 paintings and sculptures at the Galerie Fischer in Lucerne. While a number of the works sold at this auction have returned to German museums, masterpieces by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Oskar Kokoschka, Henri Matisse, and Franz Marc now hang in the Busch-Reisinger Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Basel Kunstmuseum, the Cincinnati Museum of Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the Norton Simon Museum, and the Saint Louis Art Museum.

As thousands more modern works were confiscated and sold, prices dropped and dealers selling on commission did not reap the profits that they had initially envisioned, unless they could sell in volume. Ironically, many of these dealers had been champions of modernism and rightly feared that works that were not exported (or somehow concealed) would be destroyed (as many thousands of objects were). Among these dealers were Ferdinand Möller (who had specialized in Die Brücke), Günter Franke (who retained and hid from the Nazis his Nolde watercolors), Bernhard Böhmer (a specialist in Ernst Barlach), and Hildebrand Gurlitt, the first owner of Max Beckmann’s Bar, Brown. (In 2012, over a thousand works by Marc Chagall, Paul Klee, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, among others, were discovered hidden for reasons as yet unknown in the possession of Hildebrand Gurlitt’s son, Cornelius.) As director of the König-Albert-Museum in Zwickau in the 1920s, Gurlitt had organized exhibitions on Max Pechstein, Käthe Kollwitz, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Emil Nolde, among others. He continued to support modernism as managing director of the Hamburg Kunstverein (Art Association) until he was forced to resign by the Nazis in 1933, the same year Beckmann was dismissed from his post as professor in Frankfurt. Although designated by the Nuremberg laws as a "quarter-Jew," Gurlitt’s connections for selling modern art were valuable to the Nazis. Gurlitt faced what Jonathan Petropoulos, a leading authority on the subject, has aptly called a Faustian bargain: by trading with the Nazis he could rescue modernist works from destruction by selling them abroad.

Hildebrand Gurlitt acquired Bar, Brown directly from Beckmann; it was not confiscated from a public museum nor looted from a private collection. At the time Gurlitt acquired it, Beckmann and his wife were living in desperate conditions in occupied Amsterdam. Selling off personal possessions to survive, he and his wife, Mathilde (“Quappi”), lived for a time in the home of Helmuth Lütjens, the Amsterdam representative of Berlin’s Cassirer gallery. Lütjens arranged for many of Beckmann’s paintings to be stored in the gallery warehouse, where they would be better protected from confiscation. He had been tipped off to this possibility by another important dealer in Beckmann’s life, Erhard Göpel, who, like Gurlitt, was connected by trade to the Nazis. Göpel twice arranged for Beckmann (lastly at age 60) to be exempted from the draft, and Beckmann gave him artworks in gratitude on both occasions.

It is unlikely that Beckmann or his dealers reaped great returns selling art in Germany, given that most “degenerate” artists were legally prohibited from working, selling, or even obtaining art-making materials; Beckmann’s son, Peter, serving in Germany’s medical corps, had to smuggle works from Holland to Beckmann’s loyal buyers in Germany. Nonetheless, Beckmann received vital financial support from German patrons such as Georg Hartmann, who, through Göpel’s efforts, commissioned Beckmann’s portfolio of lithographs, Apocalypse, to be printed in Frankfurt in a small edition to avoid Nazi detection. Göpel had bought five paintings from Beckmann between 1942 and 1944, and he and Gurlitt acquired another five works in September 1944, when Göpel left Holland for good. It is not known if Bar, Brown was included in this group. Mayen Beckmann, Max Beckmann’s granddaughter, was quoted recently in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung that she says the work has a “clean” history and that she has no plans to reclaim the painting, while noting, “Of course Max Beckmann would have preferred to be in the U.S. by then and to be in a situation that would have enabled him to get a better price for the painting.” (“Private Geschäfte,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, February 1, 2014, page 35.) After the war, Beckmann’s dealers continued their support, with Göpel writing the authoritative catalogue raisonné on Beckmann, and Gurlitt organizing retrospectives for Beckmann in 1947 at Frankfurt’s Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie and in 1950 at Düsseldorf’s Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen.

Peter Beckmann and Hildebrand Gurlitt at the opening of the Max Beckmann exhibition in Düsseldorf in February 1950.

Peter Beckmann and Hildebrand Gurlitt at the opening of the Max Beckmann exhibition in Düsseldorf in February 1950.

Bar, Brown was included in both exhibitions. After the war, Beckmann valued Gurlitt as an art dealer, advising his first wife, Minna Beckmann-Tube, in a letter of January 1, 1950: “For the sale of my recent paintings I believe that H. Gurlitt is the most appropriate person. He is clever and has a fine feeling for art and is fair.” As the painting’s provenance shows, Gurlitt never sold the painting: it was inherited by Gurlitt’s wife upon his death in 1956. The work was offered for sale at public auction in Stuttgart in 1960, but remained unsold. After her death in 1968, it was purchased from her estate by Galerie Roman Ketterer in 1971, from whence it was sold at Sotheby’s in Munich on October 28, 1987, to collectors Marvin and Janet Fishman of Milwaukee. The painting was among the works featured in a traveling show of the Fishman Collection, organized in 1990 at the Milwaukee Museum of Art that subsequently toured to Berlin, Frankfurt, Emden, New York, and Atlanta before being sold at Sotheby's London, on October 18, 2000, where it was purchased by Robert and Mary M. Looker, who generously donated the painting to LACMA in November 2013. From its initial exhibition to its public sales at auction and in connection with each subsequent exhibition, the provenance of Bar, Brown has been well documented.

Timothy O. Benson, Curator, the Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies