One of the great pleasures of working at an encyclopedic art museum is that it allows curators to put objects from different collection areas in conversation with each other. A perfect example is the dialogue that takes place between the artworks in Marsden Hartley: The German Paintings 1913–1915 and a companion show of works from LACMA’s permanent collection, Marsden Hartley’s Modern Influences.

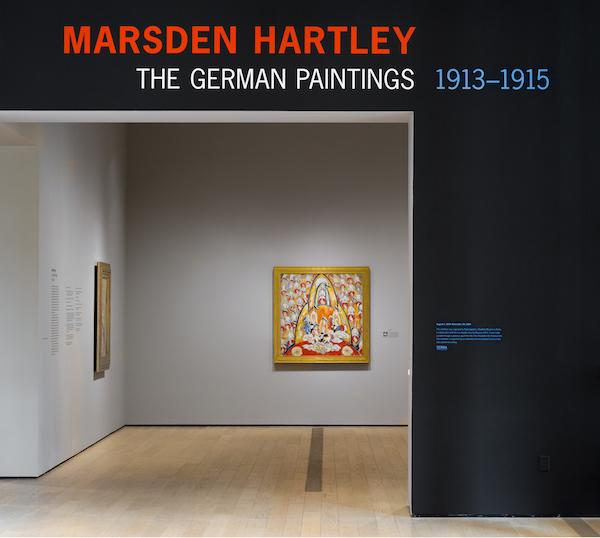

Installation view: Marsden Hartley’s Modern Influences, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

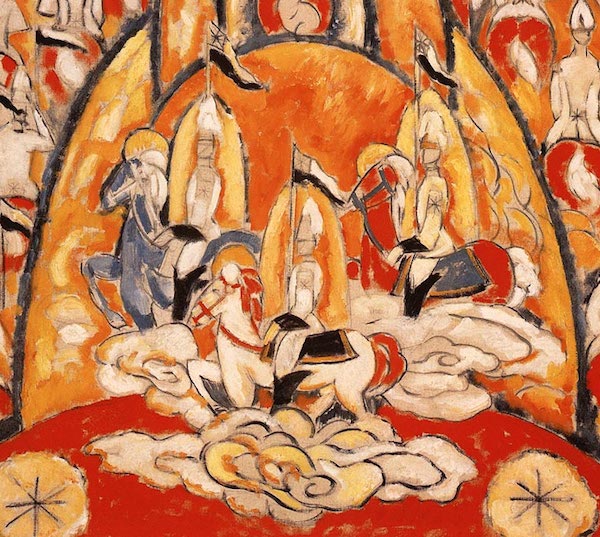

The main exhibition comprises 28 canvases that Hartley, an American artist who was a member of Alfred Stieglitz’s artistic circle, painted while living in Berlin during the period leading up to and immediately after the outbreak of World War I. Hartley’s paintings from this period—radical in their day, and still visually stunning by contemporary standards—are richly symbolic and colorful works that incorporate military insignia, animal forms, Native American motifs, musical notations, and abstract patterns.

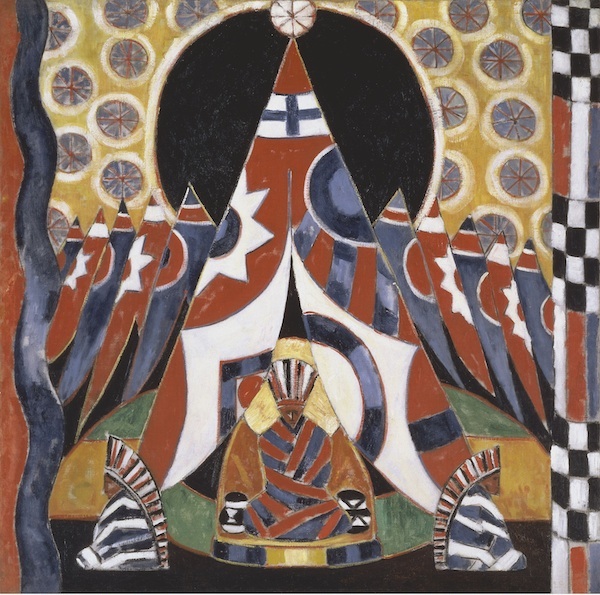

Marsden Hartley, Indian Composition, 1914–15, Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York, gift of Paul Rosenfeld, 1950.1.5

In the accompanying permanent collection exhibition, viewers can discover examples of works that may have served as source images or inspiration for his paintings. Hartley was deeply influenced, for example, by Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a group of Munich-based artists that included Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, and Gabriele Münter. In January 1913, after visiting Munich and meeting with some of the artists, he wrote to Stieglitz, “The new German tendency is a force to be reckoned with—to my own taste far more earnest and effective than the French intellectual movements.” One can see the direct results of Hartley’s friendship with the Blue Rider artists in the Berlin paintings if one looks closely at the works in the adjoining exhibitions.

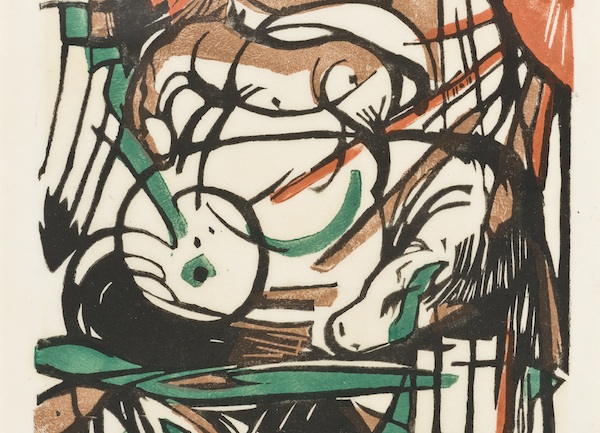

In LACMA’s 1913 color print Birth of Horses by Marc, there is a figure of a sleeping horse in the lower portion of the composition. A strikingly similar reclining horse appears in Hartley’s Indian Composition from 1914–15, which he painted during his time in Berlin. Hartley himself was explicit about the German artist’s influence; as he described in a letter to Stieglitz, “Marc is extremely psychic in his rendering of the soul life of animals. It is this which constitutes the most modern tendency—which without knowing until I had been to Munich—I find myself directly associated.”

Franz Marc, The Birth of Horses (detail), 1913, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies

Marsden Hartley, Indian Composition (detail), 1914–15 (full image shown above)

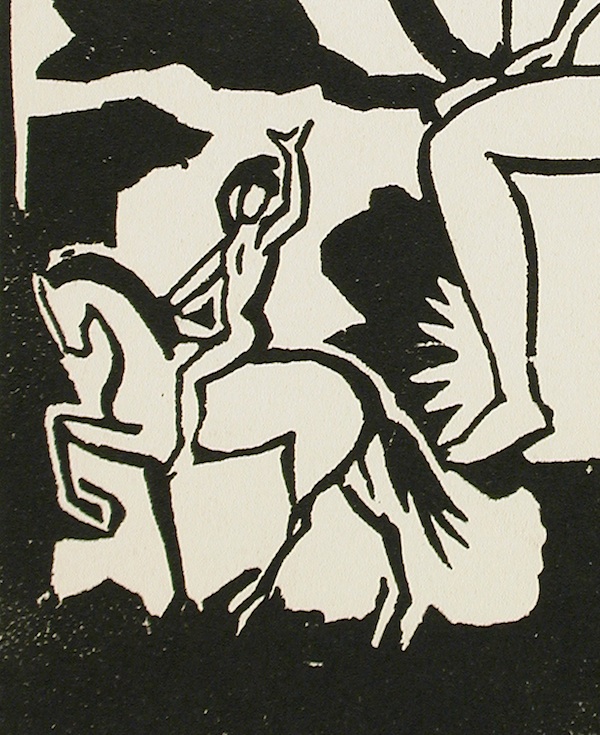

Visual connections such as this abound throughout the two exhibitions. In a detail from the lower left corner of Macke’s 1912 Greeting, one can see a horse and rider, the horse depicted mid-stride with one leg lifted. This very same motif appears in several of Hartley’s paintings, including The Warriors, 1913.

August Macke, Greeting (detail), 1912, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, M.82.288.203

Marsden Hartley, The Warriors (detail), 1913 (full image shown above)

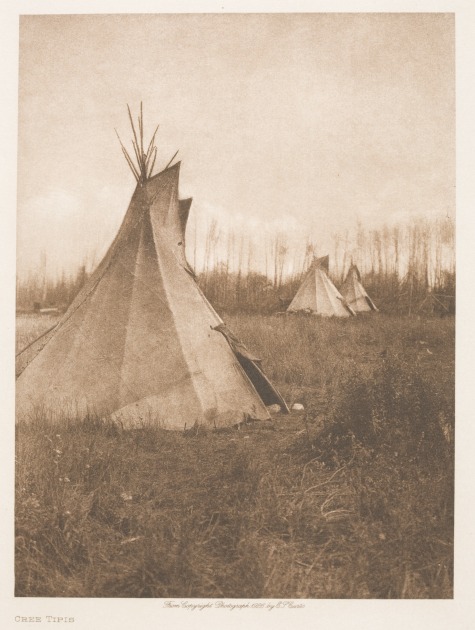

Besides the profound influence of the Blue Rider movement, one can also see the traces of modern visual culture and historical events on Hartley’s paintings—as, for example, in the apperance of Native American imagery in both Hartley’s Amerika series and Edward Sheriff Curtis’s photographs from his multivolume project, The North American Indian. Both Curtis’s photos and Hartley’s paintings—compositions rich with repeating motifs such as tipis and Indian chiefs in headdresses—reflected the growing fascination, both in the US and Europe, with Native American and other “primitive” cultures during the early decades of the 20th century.

Edward Sheriff Curtis, Cree Tipis, 1926, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of John Anton, San Diego, CA

Marsden Hartley, American Indian Symbols, 1914, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

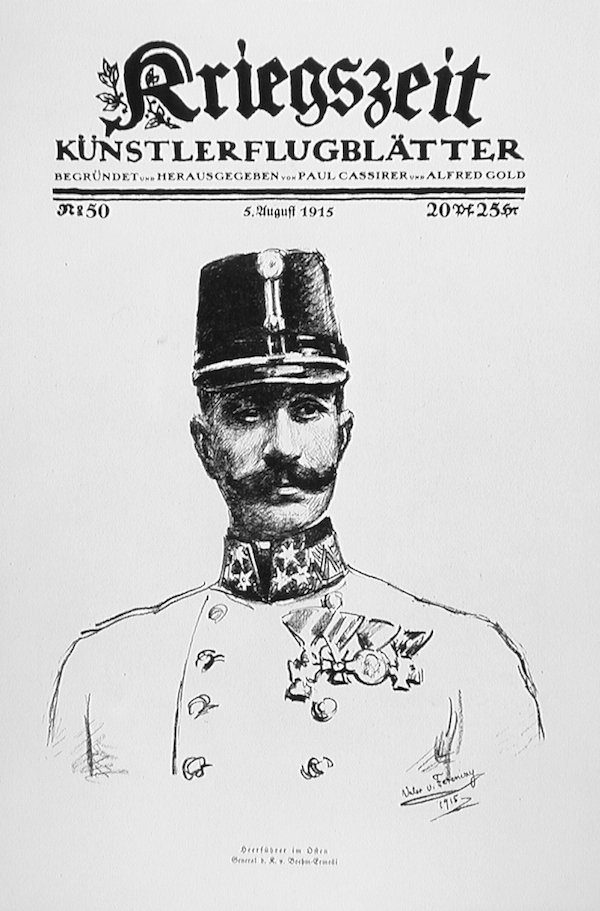

Finally, one can find direct correspondences between Hartley’s War Motif paintings, and the German officer portraits that regularly appeared on the cover of the periodical Kriegszeit (Wartime), a weekly broadsheet that was produced by art dealer and publisher Paul Cassirer between August 1914 and March 1916. In Hartley’s nonrepresentational portraits—painted arrangements of military items such as helmets, iron crosses, and flags—one can see some of the same military regalia as in the Kriegszeit covers. Though Hartley’s canvases were highly symbolic and deeply personal tributes to his beloved friend Carl von Freyburg, they also reflected the type of war pageantry that was constantly on display in and around Berlin.

Valer von Ferenczy, Army Commander in the East—General Boehm-Ermolli, 1915, from Kriegszeit, no. 50, 1915, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, purchased with funds provided by Anna Bing Arnold, Museum Associates Acquisition Fund, and deaccession funds

Marsden Hartley, Portrait, 1914–15, Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, bequest of Hudson D. Walker from the Ione and Hudson D. Walker Collection

These are just some of the visual connections that museum visitors can make between the works in Marsden Hartley: The German Paintings 1913–1915 and Marsden Hartley’s Modern Influences. For more, come see the shows before they close on November 30, and try your hand at further source hunting.