Unframed is taking a look behind the scenes to profile the dedicated people who make LACMA special. We sat down with the curator of Islamic art and head of the Art of the Middle East department Linda Komaroff to talk about reinterpreting the past and how contemporary art can help us understand a civilization.

Many people are unfamiliar with Islamic art. Can you give us an overview?

The designation "Islamic art" is not quite as straightforward or comprehensible as that of other collecting areas in the museum so I am very accustomed to expounding on this. Islam fostered the development of a unique social umbrella beneath which many cultural traditions, often practiced or sponsored by members of other religions, were able to develop and thrive; among these, most significantly from my own perspective, is the very special art form that bears the designation Islamic art. This art belongs to many disparate lands, with different cultures and diverse languages, which became through a shared faith a singular civilization.

The term “Islamic art” is closer in meaning to what we think of when we talk about Roman art—much of which was not actually made in Rome nor even in Italy. It reflects the Roman Empire, which stretched from England to North Africa and Western Asia. Roman civilization similarly is an umbrella-like term for diverse peoples speaking different languages, united by a common written language in Latin.

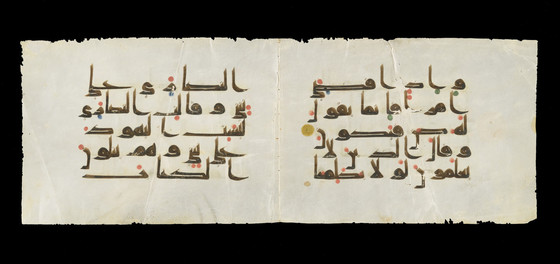

Islamic art, however, is not the art of a single empire, but multiple empires over a long period of time—the Umayyad Empire, the Abbasid Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, etc. In the Islamic world, there is a common liturgical language in Arabic and a shared Arabic alphabet. It is not that Islamic art has nothing to do with faith, but Islam created a civilization, and it is that civilization to which the art is tied.

For example, we have manuscripts of the Qur’an but works inscribed with verses from the Qur’an could have a religious or secular context. We often times cannot distinguish; for many, faith was, and is, inseparable from daily life. By analogy, we can think about America, where the majority of the population is Christian. You might have a cushion or a plaque bearing the New Testament quote "Rejoice in the Lord always," but you would not necessarily assume it had to have come from a church; most likely, it would have been used in the home.

You’ve been acquiring contemporary art from the Middle East along with historical works, including entire structures like the Damascus Room. Tell us about collecting and showing contemporary works, and how that fits into your work as a curator of Islamic art.

We are shaped by the times in which we live, the color of our skin, our native language, our religion, political beliefs—things we cannot divorce ourselves from no matter how hard we try. We are therefore always reinterpreting the past. To quote the Turkish author Orhan Pamuk, "The past is always an invented land." We can only look at things from the perspective of our own time, no matter how objective we try to be. It is one of the reasons I like having a contemporary component to the historical collection. I appreciate having the opportunity to acquire contemporary art and talk to artists in the Middle East or who have roots in the region. It helps me to see things differently when I look at art through their eyes. I believe combining historical and contemporary art helps us all ultimately to better understand the past, not just to view it as something that is dead and over with.

This is one of my motives for organizing In the Fields of Empty Days: The Intersection of Past and Present in Iranian Art, which is coming up in 2018. The first part of the title is from a line in a lengthy poem, The Ending of the Book of Kings, written in 1959 by Mehdi Akhavan-i Sales, an Iranian Marxist poet. The Shahnameh, also known as the Book of Kings, an even longer poetic work, was completed in the early 11th century but it is still relevant today.

Our hearts bound by the memory of the lambs of splendor,

in the fields of empty days,

Our swords rusty, worn out, and weary,

Our drums, forever silent,

Our arrows, broken winged.

We are the conquerors of the cities gone with the wind.

The fields of empty days is the past. The poet is perhaps suggesting that the only way Iranians can move forward is to give up the past, which was their “lambs of splendor,” the celebrated times in Iran’s history. (For many Iranians, that once meant looking to the first millennium BC, the period of the Persian Empire before Alexander the Great invaded and destroyed the Achaemenid dynasty.) The exhibition is about how the past keeps asserting itself in Iranian art and literature, beginning with the 16th century.

And why do you begin with the 16th century?

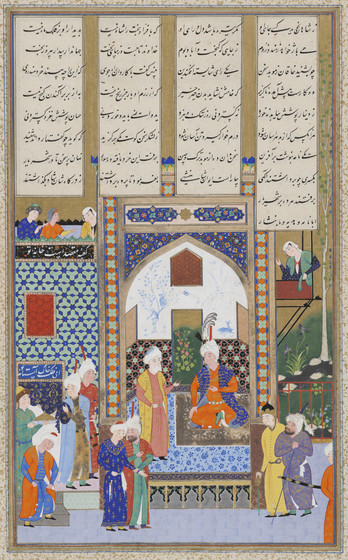

For two reasons: the Iranian national epic—the Shahnameh and Iran’s religion—beginning c. 1500— Shi‘a Islam. During this time, some of the most spectacular illustrated versions of the Shahnameh were produced. Although the text tells tales of the pre-Islamic rulers of Iran, the kings and princes illustrating the pages were depicted as though they belonged to the royal court of the day. The artists also updated their clothes and palaces, purposefully equating their own present-day princes or kings with the ones referenced in the story. This was one way of using the past to capture the present and thereby to legitimize the contemporary ruler by embedding him and his dynasty within the long history of Iranian kingship.

Also in the 16th century, Iran becomes a Shi‘a country. It was Muslim before then, but Shi’a Islam became the state religion at that time and it remains so to this day. Being a Shi‘a Muslim makes one constantly aware of the past. Shi‘a Muslims in Iran recognize a series of 12 imams, all martyrs. Most significantly, the Prophet Muhammad's grandson Husayn and his family and followers were killed on the 10th of the month of Muharram in the year 680 on the plains of Karbala in modern Iraq. This is a pivotal moment for Shi‘a Muslims; the events at Karbala were immortalized in books especially from the early 16th century on. Eventually there were plays, known as ta’ziyeh, performed by costumed re-enactors. Participants in the emotionally charged and graphic ritual are made to experience the killings and to mourn the slain in present time.

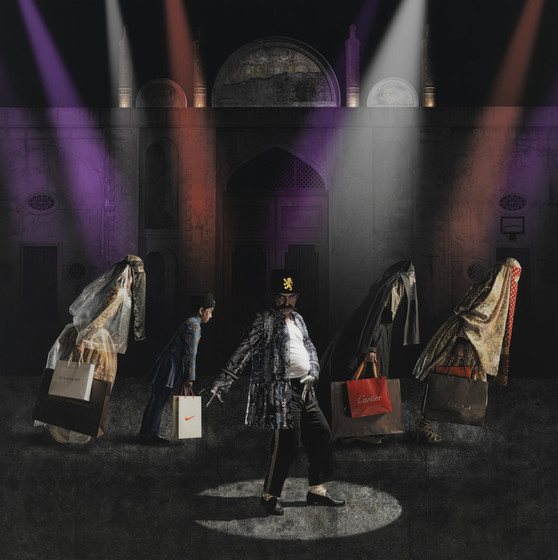

The exhibition will commence with some illustrated manuscripts from the 16th century. It will include a 17th-century manuscript depicting a prince, an ancient Iranian hero; after having slain a dragon, the prince is shown giving thanks—but praying as a Muslim. Not just any Muslim, but a Shi‘a Muslim. The exhibition moves quickly through the 18th and 19th centuries. It will focus on the 1970s to the present, when something different happens—instead of moving the past into the present, artists began shifting the present to the past as a form of barely disguised social and political criticism. It is the opposite of what artists were doing previously.

Can you give us a sneak peek of a work that will be in the show, one that puts the present in the past?

We acquired a recent series of works by Siamak Filizadeh last year that is concerned with a specific king—Nasser al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96). The artist recontextualizes Nasser al-Din Shah in the present, with cell phones, a film poster, shopping bags, and designer clothes, while presenting some of the key incidents of his nearly 50-year reign, including his assassination. The narrative is not about the past but today, a form of criticism of the leadership of the present. The artist uses Nasser al-Din Shah to show that, while there are no longer kings in Iran, perhaps the present leadership still behaves in the same manner. That is the theme of this exhibition, the shifting between past and present—it is a form of time travel at which Iranian artists seem to excel.

When you look at some of these works of art, you do not know where you are exactly in time and space; I find that most appealing. Whether in works of science fiction or films, like Inception, or in art, I enjoy the sensation of not being 100 percent certain where I am. That perhaps explains part of what appeals to me in mixing contemporary with historical art, and in choosing these particular works of art, where the artists are fusing and confusing the past and present.

I would also think that having a contemporary angle would help in drawing younger audiences.

Yes, I think that is also a key aspect of it. Since I came to LACMA , I have been concerned with the idea, especially after 9/11, of somehow encouraging members of the public (particularly those with an inquiring mind) to look at Islamic art in relationship to the people for whom it was made.

I always thought it was a stretch to expect visitors to see beautiful historical objects and relate to the descendants of the people for whom they were made. But if you root something in the present day, it is a more direct link—it is intuitive to understand your own time. With contemporary art, the connection is more immediate, the place names more relevant, and ultimately, I hope, the dismal reports and blur of media images somehow more real.

Was that what made you decide to begin collecting contemporary Middle Eastern art?

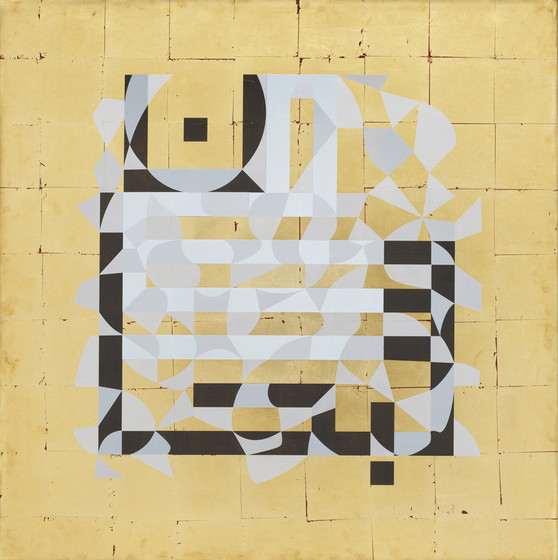

Partly. My epiphany, and it truly was an epiphany, came as a direct result of an exhibition I saw at the British Museum in 2006, Word into Art, organized by my colleague in Islamic art, Venetia Porter. This landmark exhibition focused on calligraphy and demonstrated how artists today use this classic Islamic art form but in a contemporary manner and often in materials other than ink and paper. I was startled by the revelation that the art I loved was not, in fact, dead, but lived on, sharing the same DNA with historical Islamic art: for instance, the use of writing in the Arabic alphabet as a means of communication and decoration.

But there is more: I visited Word into Art five times over the course of two weeks (certainly a record for me) and what also struck me was the deep engagement of museum visitors. They were looking and talking to one another, and talking and looking, again. For a curator, there is no greater sign than this of having gotten it right. For most curators, it is not merely about building the best, or largest or most comprehensive collection but rather it is creating an installation or exhibition that resonates and connects with an audience. When it comes to Middle East art, this has an even greater significance and in recent years a greater urgency.

I think it is important that we can be confronted with the evidence that a civilization, which we have been led to believe is meaningless, is worth respecting and preserving. It does not mean that the role of the exhibition is exclusively to educate; one cannot learn with a closed mind. For those who are willing to make the effort, such works are capable of helping the museum visitor to transcend the barriers of suspicion, prejudice, and xenophobia that sometimes separate us.

Linda’s latest exhibition, Abdulnasser Gharem: Pause, opened on Sunday, April 16, and is on view in the Ahmanson Building through July 2, 2017.