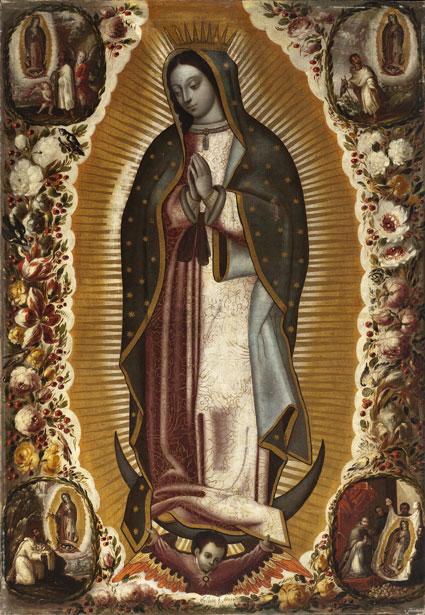

Who isn’t familiar with the iconic image of Our Lady of Guadalupe? She is without question one of the most revered and reproduced images of the Christian world. According to tradition, in 1531 the Virgin appeared to the Indian Juan Diego on three different occasions, asking him to visit Bishop Juan de Zumárraga so he could build her a chapel at the hill of Tepeyac, north of Mexico City. At first, the bishop refused to believe Juan Diego, but when he unfolded his cloak filled with the rare flowers that the Virgin had sent as proof, and revealed her miraculously imprinted image on Juan Diego’s tunic, the bishop fell to his knees and begged the Virgin for forgiveness. According to tradition the image imprinted on the Indian’s cloak is the same icon still venerated today at the Basílica of Guadalupe in Mexico City, which continues to attract millions of pilgrims each year.

Acquiring a painting of Our Lady of Guadalupe has been one of my priorities for many years, but I was waiting for just the right one. When I located this painting signed and dated by Arellano in 1691 (the surname likely refers to both Antonio and Manuel de Arellano, father and son respectively, and one of the most important family of artists of the 17th century in Mexico), I was thrilled. A few days later, after the painting arrived at LACMA, I was able to decode the barely legible inscription above his signature, which reads: Tocada a la original (touched to the original).

This made the acquisition doubly exciting, as it means that Arellano based his depiction on the original image of the Virgin. Images that were closer to the original were believed to be more miraculous and were therefore more valued. The painting must have been commissioned by someone who was in need of a miracle-making image. That this image of Guadalupe made its way to LACMA almost four centuries after it was created is just short of being a small miracle itself.