During these uncertain times, we cannot help but feel still as we pause our ordinary routine. It is an unfamiliar feeling in a hectic world. Like many of you, I have turned to art for comfort—specifically, LACMA's online collection. With over 140,000 objects spanning hundreds of years of history from all around the world to view online, I found myself coming back to the works of German-born photographer Wolfgang Tillmans. Emerging in the 1990s, Tillmans is one of the most influential and innovative photographers of his generation with works presently held in the collections of LACMA, the Art Institute of Chicago, The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, and the Kunstmuseum Basel, among others.

Deeply moved by photographs printed in magazines and newspapers he saw growing up, Tillmans is best known for his installation display methods and unconventional way of viewing a mix of genres (portraits, still lifes, landscapes, and abstractions). This atypical approach in photography has allowed him to capture "moments of being" across his artistic practice. For Tillmans, the combination of display (taping unframed photographs directly onto the wall) and composition serves to "peel away any sense of artifice in the image itself in order to make the photograph disappear and leave the viewer alone with what [Tillmans has] been looking at."¹ Each context offers a moment of stillness and reflection—a reflection that can, in some way, help us try to make sense of our current situation.

As seen in LACMA's 2012 exhibition Figure and Form in Contemporary Photography, Wolfgang Tillmans's Los Angeles Installation 1996-2002 is a series of photographs, 14 of which are in LACMA's collection. The series includes photographs of eclipses, rainbows, stars, puddles in the sidewalk, books, nature, food, beverages, clothing items, melting glaciers, coffee tables, and friends: laying, posing, dressing up, and walking on the beach. With these photographs printed in varying dimensions and orientations, Tillmans places them in a constellated installation to blur the lines between photographic naturalism and studio photography. The configuration of isolated moments offers a micro analysis of social and behavioral events that from our current perspective on time, space, and the body, allow for a temporal sense of contemplation and meditation. As we practice social distancing, these isolating moments can be extremely discouraging and daunting. However, like the constellation of Tillmans's images, we are inescapably interconnected. In these past weeks, people have come together—physically 6 feet apart, or digitally—to solve problems and encourage each other to continue moving forward.

While finding beauty in these moments with people, places, and things, Tillmans does not interpret the moments he captures as portraits and still lifes. He explains, "That's how I want to convey my subject matter to the viewer, not through the recognition of predetermined art-historical image categories but through enabling them to see with the immediacy that I felt in that situation."² His LA still life documents an off-centered aerial view of a wooden table and three chairs. A crystal glass with two decaying mini pineapples on long crisscrossed stems sits at the center of the table accompanied by a scattered positioning of fruits and vegetables to its lower left. With a variety of muted tones and textures, the arrangement consists of salt and pepper shakers amid imperfectly shaped potatoes, apples, and figs. The absence of a sense of time or space offers the viewer the liberty to embrace the stillness and reflect on the accumulation of visual information. At a time when food is a source of anxiety and tension, Tillmans's direct vision reminds us to admire the beauty and blessings in our quotidian details. As we indulge in the privilege to self-isolate at home and contemplate, we greatly appreciate the many people who are at the forefront of providing society's basic necessities.

A compelling alternative to landscape and still-life photography, wake depicts the aftermath of festivities at dawn. The composition consists of red Christmas lights dangling from the industrial ceiling; soda bottles, cups, trash, and mats scattered across the floor; four chairs and a table on the left side of the photograph; and red window frame shadows reflected onto a white wall. Tillmans carefully photographs the observation of a generation's behavior and attitudes in this photograph. Wake reconciles the raw reality with the celebration of generational and cultural moments. Comparably, social media platforms are currently full of "quarantine content": snapshots of cramped apartments, uncannily deserted street scenes, closed entertainment venues, and cautious supermarket shoppers often mirroring Tillmans's wake. While encouraged to practice social distancing, people are turning to art and art-making to document their realities. We pause and reflect on our attitudes and self-perception surrounding our past, current, and future behavior.

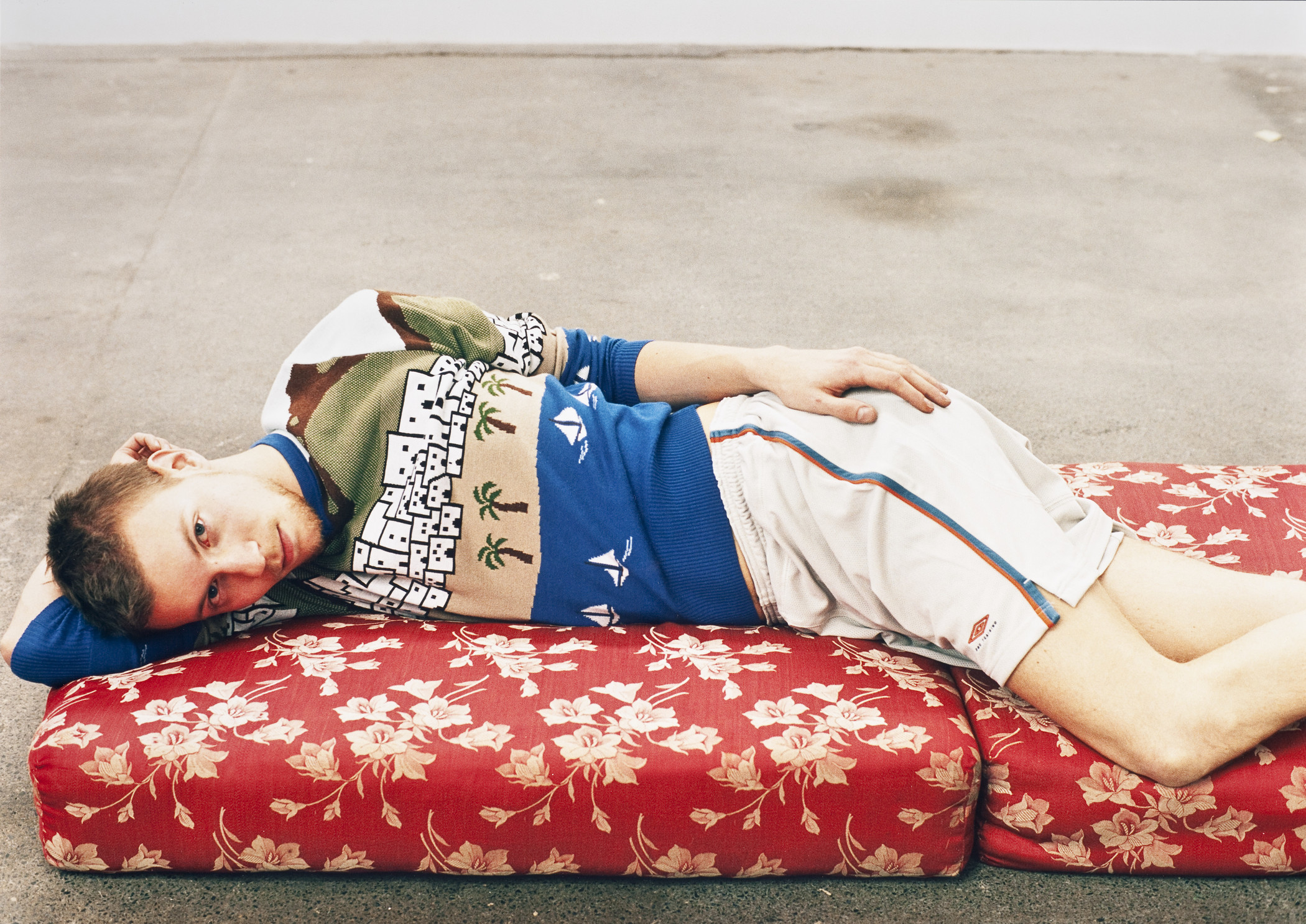

Just as he captures environments once occupied, Tillmans photographs the evocative and intimate presence of individuals with "their own styles, their own vulnerabilities, their own self-confidence and sense of how they want to present themselves."³ In Volker, lying, the male figure lays on two red floral cushions and poses—his head rests on his right bicep, his left arm outlines his torso, and his right hand rests on the side of his hip. With a playful yet vulnerable pose, the male figure confidently stares back at the viewer. Similarly, we might also find ourselves "lying and staring" intensely at our TV screens during this pandemic. We, too, break from our routine, let go of our personas, and reveal our vulnerabilities during these long periods of self-isolation at home. Our vulnerabilities might reflect anxiety, stress, insecurities, nostalgia, gratitude, peace, or relaxation. In the manner that the portrait becomes part of a larger composition and dialogue when installed and recontextualized side-by-side with landscapes, abstracts, and still lifes, we too are part of something bigger. We are not going through this alone.

In this series, Tillmans thoughtfully documents a variety of environments—some previously occupied by people, others untouched and incomprehensible, and some including his close friends and acquaintances. While each photograph depicts an unconventional perspective, the accumulation of detail offers the viewer a reflective composition—a moment of stillness that, when recontextualized in the totality of the series, Los Angeles Installation 1996-2002, comforts and relieves the viewer. Wolfgang Tillmans's deceivingly straightforward documentation of moments pushes genres, boundaries, and narratives. His ever-evolving work is perceptively impactful as it connects us with one quotidian environment to the next. As our perception of everyday life continues to be paused, let us embrace Tillmans's philosophy of finding beauty and reflection in each moment of being. Whether we are socially distancing by ourselves or with loved ones, maybe this is how we make sense of our current reality and start healing physically, emotionally, and mentally.

¹ Nathan Kernan, “Wolfgang Tillmans: Moments of Being,” in Apocalypse: Beauty and Horror in Contemporary Art, 2000.

² “Wolfgang Tillmans in Conversation with Mary Horlock,” in Wolfgang Tillmans, If One Thing Matters, Everything Matters, (London: Tate, 2003), 303. Exhibition Catalogue.

³ Russel Ferguson, “Faces in the Crowd,” in Wolfgang Tillmans, (Los Angeles: Hammer Museum LA (Ed.); New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2006), 69. Exhibition Catalogue.