We are deeply saddened by the passing of Dr. Samella Lewis, a renowned artist, scholar, educator, and curator who was a pioneer in establishing the field of African American art history. A tireless advocate for visibility and inclusion of Black artists and women artists in museums and galleries, Lewis created opportunities for other artists of color and was a mentor to many.

Born in New Orleans in 1923, Lewis showed an early interest in art, and used drawing as an outlet to express anger and frustration about the reality of growing up in a racially segregated society. In 1940, at Dillard University, she met her mentor Elizabeth Catlett, whom she followed to Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) to complete her undergraduate degree in 1945. She became an expert on Chinese, African, and African American art and culture, earning both an MFA and PhD in art history from Ohio State University.

In 1966 Lewis moved to Los Angeles, and quickly became a pivotal figure in the development of the Southern California art scene. In 1969 she started an art publishing house—collaborating with Ruth Waddy and E.J. Montgomery—that highlighted Black artists; she helped to organize the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists the following year; opened a commercial gallery around 1972; founded the Museum of African American Art in 1976; and established (with others) Black Art: An International Quarterly (now The International Review of African American Art) that same year. Lewis also published countless genre-defining books on Black art and art history.

From 1970 to 1984, Lewis taught African, Native American, and Chinese art history as well as Black Studies at Scripps College, where she simultaneously directed the Clark Humanities Museum and ultimately became the college’s first tenured Black professor. Her legacy there includes not only the host of students she taught—including, notably, Alison Saar, who has acknowledged her as a mentor—but also the Samella Lewis Scholarship for Black students, established in 2002, and The Samella Lewis Contemporary Art Collection at Scripps’s Williamson Gallery, launched in 2007 in her honor, with a special emphasis on work by women and Black artists. Lewis received numerous teaching awards and other accolades, including multiple honorary degrees and the UNICEF Award for Visual Arts; in 2000 she was recognized by Congress for her service to the community. Last year, she was awarded the College Art Association’s Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Lewis had a longstanding connection to LACMA. As a result of advocacy for greater representation of Black artists at the publicly-funded museum by the Black Arts Council (1968–1974), Lewis was invited to deliver a lecture in 1969. The talk, “The Relationship of the Black Artist in Our Society,” broke museum program attendance records. She was hired as education coordinator and produced several successful programs along with the Black Arts Council, including radically diversifying children’s programs and the student body. However, frustrated by the slow pace of change at the museum to include artists of color, she resigned the following year. Her departure was followed by months of protests, and this turmoil was part of the impetus, in part, for LACMA’s subsequent exhibitions that began to remedy the exclusion of Black artists, such as Three Graphic Artists: Charles White, David Hammons, Timothy Washington (1971) and Two Centuries of Black American Art (1976). Lewis’s dedication to making room for Black artists led her to create several arts spaces in Los Angeles, and she was part of a wave of efforts for greater inclusion in arts institutions nationally in the 1960s and ’70s. While her activism is celebrated today, at the time she was the target of harassment for her efforts.

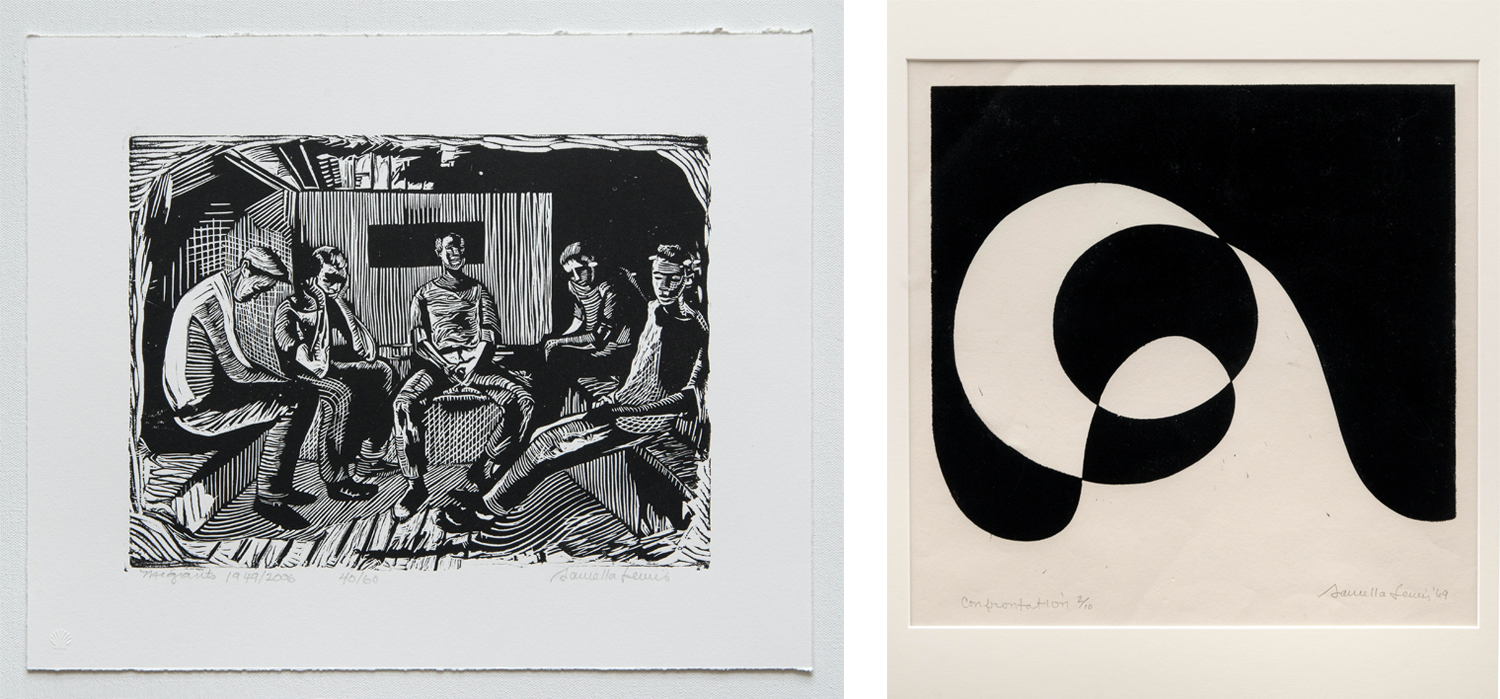

Lewis also has significant stature as a practicing artist and is known particularly for figuration; several such works by her have recently entered LACMA’s collection. Her earliest artistic sensibility was shaped in part by African traditions and spiritual beliefs as translated via Louisiana; her early works typically portray family members and other subjects familiar to her. In her later work, she chose to portray figures who more generically express ideas, emotions, and social conflicts.

Acquired in 2022, a selection of eight prints represents a survey of her printmaking practice over 50 years and portrays a variety of subjects and moods. Migrants, a linocut from 1949 (reprinted 2006), represents a moment of seeming dejection or reflection, while Children’s Game (1968; reprinted 1982) conveys the sense of joy and hope in togetherness. Confrontation (1969) suggests the notion of opposition, black versus white, in a rare abstract image by the artist that likely relates to her civil rights activism. Made the same year, Prophet demonstrates Lewis’s stylistic range while also acknowledging her appreciation and knowledge of art history; the elongated face and carved lines evoking tribal arts as well as German Expressionist prints.

Later lithographs, such as House of Shango (1992), Cleo (1996), and Together We Stand (1997), which was made in collaboration with poet Maya Angelou, show her facility with a litho crayon to sensitively portray figures who all embody strength, resilience, and fortitude in unique ways. Finally, the screenprint Creole Mules (1995) exploits the saturated color typical of the technique to capture a memory from Lewis’s childhood in Louisiana.

In the 1970s, the artist created a painting titled Bag Man and sold it directly to a collector. When she later requested a loan of the painting for an exhibition and the collector declined, she used her resulting frustration as the impetus to create a second version in 1996. This second painting exceeded her expectations, and she proclaimed it “better than the first one.” Created as a recollection of her childhood when there were no garbage trucks and men came by to pick up the trash, the image for Lewis was an appropriate metaphor for today’s social justice issues. Lewis was passionate about the stark inequities and discrimination targeting “our people,” “especially those who struggle out on the street, picking up cans and whatever else they can find just to live.” Acquired in 2022, Bag Man was on view in LACMA’s recent exhibition Black American Portraits (2021–22), and will be included in the upcoming tour of the show.

Further Reading:

Now Dig This!: Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980 digital archive

Kellie Jones, South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s, 2017, Duke University Press