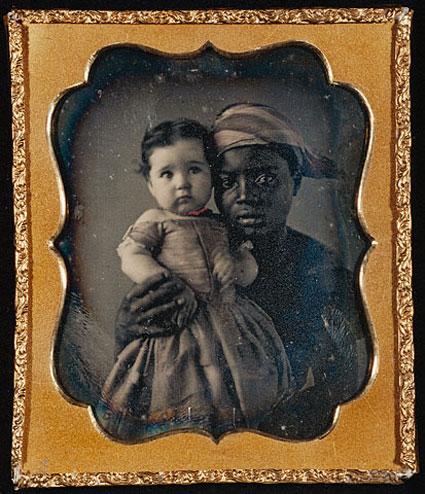

Nurse and Child, an American daguerreotype made about 1850 by an unknown photographer, is an arresting image. It was the unflinching directness of the nurse’s gaze and the beauty of her face that first fixed my attention. Although this daguerreotype appears in the current Getty exhibition, In Focus: The Worker, which “presents a photographic history of working people across many cultures,” I can’t help but look at Nurse and Child through the lens of LACMA’s current exhibition, American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765–1915.

Unknown American, "Nurse and Child," about 1850, hand-colored daguerreotype, image courtesy of the Getty Center

Like so many of the paintings in LACMA’s exhibition, what is riveting in this photograph is how the details and the composition offer clues about the complex relationships between blacks and whites in nineteenth-century America. Here an African-American caregiver, who may or may not be a slave (we don’t know where she lived), is pictured with her white charge, who appears to be around the same age as my own eight-month-old son, a feature that surely drew me further into the image. Her remarkably long fingers do not grip the baby’s hand with a fist but extend delicately along the child’s arm to softly restrain it from batting, like the impulse of the child’s other hand, and therefore blurring, “a necessary gesture in early photography, when exposure times were usually too long for a child to sit still,” notes Getty curator Paul Martineau. The nurse presses her head gently against the baby’s to keep it close, comforted, and stationary. The tenderness with which the nurse effectively collaborates with the photographer to achieve this image—ostensibly a double portrait—is palpable.

It is also clear, however, that the focus is on the white baby, who is dressed in a bright costume and is held to stand above the eye level of her nurse, in front of her, and in the light. Aside from the neatly tied, light-patterned headscarf, the figure of the nurse recedes into the background. Yet her face is aligned along the same plane as the baby’s, indicating at once their close bond and suggesting the dependence of a white family on the care and labor of African Americans. Such relationships are evident in many paintings in American Stories.

Mount, William Sidney, "Eel Spearing at Setauket," 1845, Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, photo courtesy of Fenimore Art Museum, photo by Richard Walker

Consider Eel Spearing at Setauket, painted in 1845 by William Sidney Mount, which shows Rachel Hart instructing her young charge George Washington Strong on how to spear eels, or Winslow Homer’s Cotton Pickers, whose protagonists possess a stoic beauty akin to that of the nurse. While Nurse and Child portrays two actual if unknown individuals from 1850s America, we want to make up stories about their lives, stories that contemporaneous American painters often set to canvas.