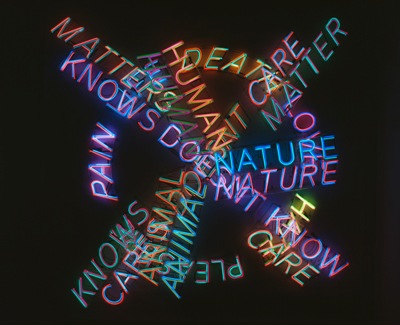

Upon first seeing Bruce Nauman’s neon sculpture Human Nature/Life Death/Knows Doesn’t Know—on view in the current exhibition Human Nature—I attempted to count the nineteen (dare I say) somewhat “apocryphal” words as a collective while they flashed dizzyingly before me. I suddenly had this thought that the only words missing were “sin” and “devil” and I could have heard these on any given Sunday from a Baptist preacher. Of course, this is the absurd universe that art lives in: what could have been said, what should have been said, and what one wished was said, all leading back to the piece itself.

Bruce Nauman, Human Nature/Life Death/Knows Doesn’t Know, 1983, Modern and Contemporary Art Council Fund

For Nauman, a sort of Pop Existentialist with a Conceptualist’s heart of gold, this was the game! Words and meanings, anagrams, palindromes, puns, and the humorous hide and seek—Nauman had a passionate attraction to the paradox of language. That is not to say he was a romantic, as on most levels he was a consummate realist, but he thought “art ought to have a moral value,” to quote Joseph Ketner II’s essay “Elusive Signs.” It was the 1980s: it may have been “Morning in America,” but it was politically dark in South Africa and Africa in general, and Nauman took this to heart. And yet, here’s a guy who fed on the intriguing ideas of Ludwig Wittgenstein in which meaning was not shared by an object and its name; and Vladimir Nabokov of Lolita fame, a novel of dastardly exquisiteness; and also Samuel Beckett, the master of the haunting otherness. Language had to be this, metaphorically speaking, convertible ‘mercury vapor’ driving through the heart of the American dream, prepared to ignite confusion and sow tension.

Thus his neon art, a commercial appropriation, would slip through the harness of the consumer’s earnest trite and in its bright glowing attempt to lay some profundities at the unexpected feet. Nauman’s devilish instinct of melding whimsy and danger while lacing lascivious undertow fills his art with misdirection. Aesopian edicts in decadent clothing! It had that burst of the social shock awareness of graffiti, the New York City subway’s epidemic. It spoke on the same level, hyper, imposing, a sort of in-your-face grandeur. But legible! And although it is said that he made grander sculptures than Human Nature, none quite capture its quintessential completeness. Its zany romp, a radiant moronic heartbeat chaotically circulating its speedy reminders of the human condition, and yet perversely it could be an algorithm away from being a video game. Words leaping out of ashen shadow tubes as flares in day-glo flashes, “life-love-hate-death-pleasure-pain,” winking in circular stop motion, and layered, star-like with, “matters-animal-nature-human-matter,” imposing blazingly with verbs of “knows-cares-doesn’t know-care,” and for an exhilarating second, all are lit at once. Nauman, highly self-conscious, knew the risk of these semiotic wonders. Human Nature could be a street sign rant, first cousin to “The End is Near,” though in his carnival glitz, it is somehow comical and redundant, like a beer ad in his first studio or those cafes at roadside truck stops, all racy hues and tart glamour. And for all of Human Nature’s faults, and maybe a defeat of its message, it remains exquisitely beautiful.

But in its afterlife, the year 2011, in the 140-character twitterverse living in the six-second attention span world of “it’s cool,” “it made me dizzy,” “it was so psychedelic,” Bruce Nauman’s Human Nature, still, begs to please in its vaudevillian neon that nature in its infinite jest is entertainment and where the product of human folly never quite fails to be a laughing matter.

Hylan Booker