As I mulled over LACMA’s new installation Rostam 2–The Return, I found myself thinking: “What on earth do Superman and Rambo have to do with one of Iran’s oldest texts? “

Rostam 2–The Return, on view on the fourth floor of the Ahmanson building, is drawn from the museum’s ever-growing permanent collection of contemporary Middle Eastern art. In this sixteen-print series, artist Siamak Filizadeh recounts the Shahnama, or Book of Kings, within the context of twenty-first-century Tehran through a kitsch-colored lens.

The Shahnama is a 50,000 couplet poem that dates back to 1010 AD and is a frequent subject in Iranian poetry, art, literature, music, and cinema. In his series, Filizadeh recounts the popular tale of Rostam, a mighty mythical warrior, who unknowingly encounters his son Sohrab in combat.

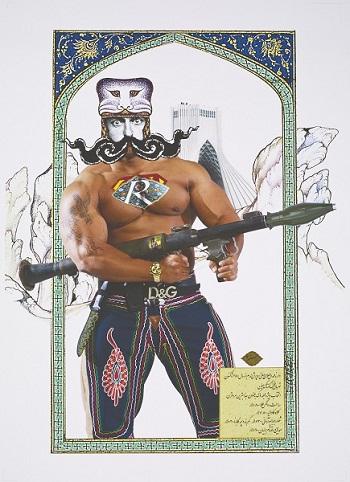

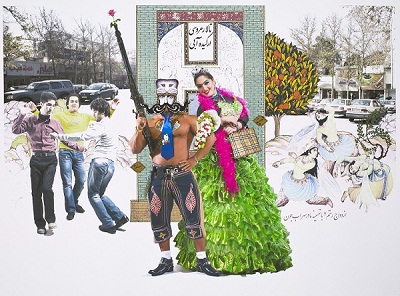

Rostam 2–The Return is an extravaganza of playfully contemporary iconography that occasionally mingles with formal traditions of Persian miniature painting. With its references to pop culture and mass communication, Filizadeh’s body of work reveals the artist’s background in both advertising and graphic design and his consequential penchant for the language of pop-consumerism.

Siamak Filizadeh, Untitled, from Rostam 2—The Return, 2010, purchased with funds provided by Karl Loring and Art of the Middle East Contemporary, © 2012 Siamak Filizadeh

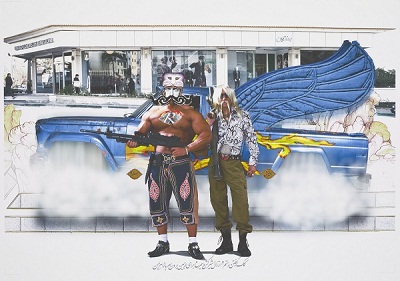

As curator Linda Komaroff puts it, Rostam is depicted as “a bazooka-toting, bare-chested body builder” (with the Superman logo emblazoned on his chest and a Rambo decal plastered on his gun) who fearlessly gallivants upon a Pimp My Ride–style motorcycle-horse hybrid. He is set amid Iranian cityscapes teeming with billboards, apartment blocks, and storefronts (did Rostam buy those pants at United Colors of Benetton?), which are nestled amidst undulating peaks of a more two-dimensional painterly mountainside.

For me, the loud digital collages read like headlines, and indeed, a portion of the artist’s retelling is conveyed through fictional tabloid covers, with a blend of Persian and English alluding to the universal attraction of celebrity culture – even when, as in the case of Rostam, celebrity is a myth.

Siamak Filizadeh, Untitled, from Rostam 2—The Return, 2010, purchased with funds provided by Karl Loring and Art of the Middle East Contemporary, © 2012 Siamak Filizadeh

Bypassing culturally-specific storytelling templates in favor of a globally recognizable visual vocabulary, Filizadeh questions the sociopolitical implications of consumer ideals in Tehran today. He asks the same of pop culture—which is where our friends Superman and Rambo come into play—by highlighting the absurdity of aggrandizing Western icons in a context where ideological liberties from the same culture are not necessarily welcomed with the same warmth.

Siamak Filizadeh, Untitled, from Rostam 2—The Return, 2010, purchased with funds provided by Karl Loring and Art of the Middle East Contemporary, © 2012 Siamak Filizadeh

During my last conversation with Linda, she commented on the way in which contemporary art from the Middle East and its diaspora augment her understanding of classical Islamic cultural production. Through these works she is able to glean richer readings of older texts, traditions, and objects.

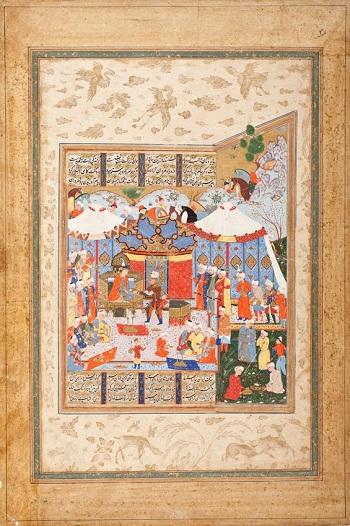

Rustam Approaching the Tents of King Kubad, page from a manuscript of the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Firdawsi, Iran, Shiraz, 1550–1575,the Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection, gift of Joan Palevsky, photo © 2012 Museum Associates

This comment resonated with me as I meandered from Filizadeh’s installation into LACMA’s Art of the Middle East galleries. Equipped with a new appreciation for the Shahnama, I began noticing more classical pieces related to the epic poem, such as Rustam Approaching the Tents of King Kubad, Page from a Manuscript of the Shahnama (Book of Kings). (The incongruous spelling of Rostam’s name in different versions of the story can be chalked up to the subjectivity of translation.) I was stricken by the formal similarities between this work dating back to 1550 AD and Filizadeh’s compositions: the flatness of perspective, the tranquil rendering of mountains, the placement of script, even the lean portrayal of horses—although horses in this earlier work don’t have flames roaring from their saddles nor chrome hind legs. It was a pleasant reminder that contemporary art and history mutually enrich one another if we’re willing to take the time to allow them to do so.

Stephanie Sykes, Communications Manager