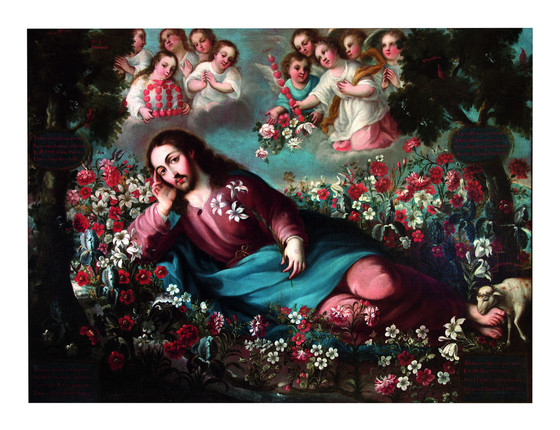

Growing up in Mexico City, I was keenly aware of the legacy of the so-called colonial era. To my then untrained eye, the many paintings that I saw in museums and adorning the walls of churches across the country seemed bold, full of color and expressive power. Now, some 25 years later, after looking at and studying this material more in earnest, it seems as vital as ever, replete with original pictorial and iconographic twists and turns, especially when compared to European painting, a tradition to which it is clearly connected. The relationship with European art, however, does not follow a center-periphery model, as the art of this period has sometimes been discussed. Eighteenth-century Mexican painting evidences the greater internationalization of art at the time and therefore can be seen as a brilliant reinvention rather than as a by-product of European models.

During this period local schools of painting were consolidated, new iconographies were invented, and artists began to group themselves into academies. Painters also became more cognizant of the impact of their own contributions, in part owing to the sizable number of works that were exported to Europe, throughout Spanish America, and within the viceroyalty itself. This awareness led many educated painters not only to sign their works and emphasize their authorship but also to make explicit references to Mexico as their place of origin. The Latin expression Pinxit Mexici (Painted in Mexico), or other variants thereof, such as Fecit Mexici (Made in Mexico), and Faciebat Mexici (Was making in Mexico), either in full or abbreviated form, eloquently encapsulates the painters’ pride in their own tradition and their connection to larger transatlantic trends.

For a long time individual styles in 18th-century Mexican art were hardly examined, save for a few cases, like that of the celebrated Miguel Cabrera. Recent scholarship, particularly of the last two decades, has shined a spotlight on several artists and their manifold contributions, providing a richer and much more nuanced picture of painting in this period. The number of uncovered and unstudied works, however, remains overwhelmingly large.

In 2011, as I began thinking of organizing an exhibition devoted to 18th-century New Spanish painting, I approached three colleagues from Mexico and Spain to join me in this most pleasurable adventure: Jaime Cuadriello, Paula Mues Orts, and Luisa Elena Alcalá. Over the last six years we have traveled exhaustively throughout Mexico, camera, flashlight, and measuring tape in hand, visiting convents, public institutions, and private collections, often pulling works out of dusty closets and treading through largely forgotten places that were once manifestly grand. This is a bond of several years now, with many ups and downs along the way, traveling in cars, buses, and small propeller planes, with one common goal in mind: to see and learn as much as we could. What we discovered was an unimaginable wealth of images, large and small, some well conserved and others on the brink of vanishing due to inclement conditions—yet all teeming with life.

It can be difficult to convey the grandeur of many of the pictures we saw in situ through an exhibition or book, as in truth only by visiting these places can one grasp the full extent of their power. Also, many of these works cannot be removed from their original contexts and displayed in a museum. The question, then, was how to do justice to such a vast pictorial output through such a proportionally small project. In the last six years we have met regularly in Mexico, Los Angeles, and Europe to discuss the works we thought would most effectively represent the field and how best to organize the presentation—invariably a subjective exercise. To this end we decided to combine a chronological and thematic approach through over 100 works, focusing on a series of what I like to call “expansive synchronic moments” (which we organized into various thematic groups titled “Great Masters,” “Master Storytellers and the Art of Expression,” “Noble Pursuits and the Academy,” “Paintings of the Land,” “The Power of Portraiture,” “The Allegorical World,” and “Imagining the Sacred”).

Ours is by no means an exhaustive presentation nor is it intended to create a canon of images by emphasizing some works over others. Rather it is conceived as a point of entry to key artists who contributed to the development of painting at the time, as well as some of the subjects and pictorial categories that were prevalent. Our hope is to offer new perspectives and bring more works to light (several scarcely known or restored especially for the exhibition). In all, we aim to share our collective passion and open up a vista on a sophisticated and innovative body of work, one that is contextually rich and highly rewarding to look at and study.

Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici and the accompanying publication (in both Spanish and English editions) also represent a continuation of LACMA’s longstanding commitment to the extraordinary legacy of Latin American art from all periods. Our dedication stems from our firm belief in the artistic and historical sophistication of the material and the importance of providing audiences with more opportunities to view and study these works as part of Western art history.

As the traditional boundaries of art history continue to shift, previously underrecognized materials are gaining more attention and inviting new and more expansive approaches. Though more and more museums and universities are paying attention to Spanish colonial art, there is still a serious need for more focused perspectives that can help cast light on the bigger picture. This makes the field particularly exciting, and we are proud to be at the forefront of this endeavor.

We hope that the exhibition and catalogue will delight audiences, and stimulate a new generation of scholars to delve further into the many intricacies of this compelling field of global art history. Organized as part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, Painted in Mexico is one of a handful of historical exhibitions focusing on the legacy of Latin American art before the 20th century.

Painted in Mexico opens at LACMA on November 19. Member Previews are November 16–18. Join now to experience this exhibition before it opens to the public! After its Los Angeles presentation, the exhibition will travel to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it will be on view April 24–July 22, 2018.