This special sewing box tells us many stories: stories of artistic exchange through the materials and motifs used, stories of life in Mexico through the vignettes that unfold in painted scenes, and stories of hidden secrets that we only discovered while installing the work in LACMA’s exhibition Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800.

Known in Spanish as a costurero or almohadilla, this sewing box was created in Pátzcuaro, Mexico, which was one of the main centers for lacquered commodities in Michoacán in the 18th century. Fine inlaid lacquer objects had been produced in the region since ancient times. Artists employed mixtures of natural oils and mineral clays to produce a glossy, water-resistant substance to decorate gourd vessels. After the arrival of the Spaniards, artists in Pátzcuaro used similar materials for the base of many furnishings, on which they brush-painted their designs. The method was similar to japanning, a process developed in Europe in imitation of the Japanese nanban lacquerware made for foreign markets. The addition of gold leaf or powder in objects like this sewing box resembled the Japanese process of maki-e, which consisted of adding gold and other metallic powders to hardening lacquer sap, heightening their sense of preciousness.

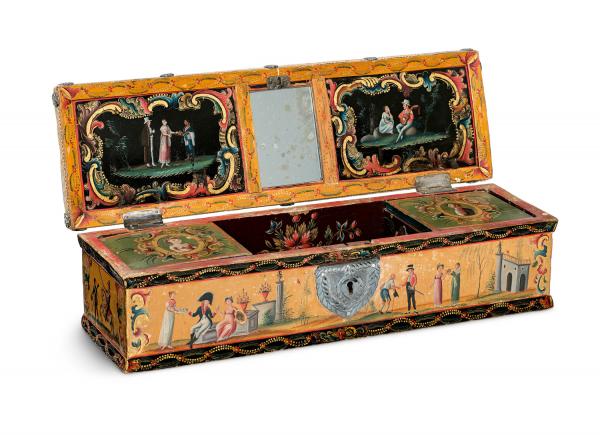

The box’s painted decorations feature a range of motifs, including Asian willow trees, Neoclassical architecture, and European Empire dress styles for the women. These elements provide the backdrop for detailed narrative scenes of courtship, charity, and battle. The characters that appear in these vignettes repeat throughout the box and are featured on the miniature portraits that appear atop the box’s hinged panels and on the bottom of the interior.

The portrait panels open to reveal two more full-length figures painted on their underside. These hinged doors introduce an interactive element to the box and its narrative, as does the mirror on the lid—where the box’s original owner would have viewed herself.

The more Europeanizing courtship and battle scenes on the box’s exterior contrast with a vignette inside the lid, which portrays a female protagonist reaching toward a platter of fruit carried by an Indigenous woman wrapped in a rebozo (shawl). Encircled by a lavish Rococo frame, this detail places the scene in Mexico, reminding its owner that the cherished luxury good that drew on foreign traditions was an unmistakable product of New Spain.

As we were installing the box for the exhibition, the two interior panels felt somewhat loose. Curious to learn more about these elements, curator and department head Ilona Katzew and objects conservator Silviu Boariu carefully lifted the inserts to find that each revealed a hidden drawer below! Delicately painted with floral motifs, these false walls match the interior and ingeniously conceal the box’s innermost sections. Secret compartments were not uncommon in luxury furniture items in Europe and the Americas—from small boxes like this to larger cabinets and desks—to store valuables or private notes. By the late 16th century, cabinetmakers introduced hidden components as a way to show their skill and to afford their patrons privacy and security. We can only imagine what clandestine possessions might have been tucked into these drawers—perhaps gold coins, jewelry, a special sweet, or a secret note? This and other fascinating boxes from the Spanish Americas are currently on view in Archive of the World through October 30; visit to see what secrets and stories you might discover for yourself.

Further Reading

Katzew, Ilona, ed. Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and New York: DelMonico Books 2022, cat. 75, pp. 298–301 (entry by Rachel Kaplan).