Last week, I visited the galleries in BCAM, Level 2, where A Universal History of Infamy was being installed. A sprawling exhibition across three venues—LACMA, 18th Street Arts Center, and Charles White Elementary School—A Universal History of Infamy engages 16 U.S. Latino and Latin American artists and collaborative teams to challenge any notion of absoluteness with regard to what constitutes Latin America and its diaspora in the U.S., the art associated with it, and how to approach this complex region.

Amid the noise of hammers and drills, I chatted with exhibition curators Rita Gonzalez, José Luis Blondet, and Pilar Tompkins Rivas about the genesis of the show and the underlying ideas that drove the curatorial process.

How did the exhibition come about?

José Luis: We knew from the beginning that we didn’t want to offer a thematic exhibit or a survey of contemporary art in Latin America. We didn’t want to go to different Latin American countries and select artworks to bring to L.A. For us, it was important to offer options and opportunities to the artists to fully take advantage of PST as a platform. It was important to have the artists in L.A. for a period of time so they could think in advance of ways to engage with LACMA’s collection, LACMA itself, the city and its art scenes, along with PST: LA/LA at large.

Pilar: The idea for artists to come to Los Angeles and do residencies at 18th Street Arts Center was a foundational part of the structure of the exhibition. In this way, the exhibition is expanded across time, and also across different sites. Allowing artists the time to do research onsite became an anchor for the development of many projects. With artists based in L.A., we still wanted to have a long engagement with them to allow ample time for the conceptualization of the works you now see on view in the galleries, and wanted to think about the project as having a decentralized, and more lateral relationship to the museum and the city.

Was your approach informed by the link between LA/LA (Los Angeles and Latin America) in the PST initiative?

José Luis: For the last four years, I’ve been wondering what the slash in LA/LA means. What kind of relationship it suggests between those two identical terms, LA and LA. Is it a question mark? Is it an equal sign? Or does it mean those terms are opposite? So rather than establishing a fixed meaning we wanted to play along, and try to unravel that symbol and those possible connections between LA and LA.

Rita: We also question problematic assumptions about art and artists who are located outside the “epicenters” of cultural authority. It’s not just in Latin American art, but if an artist is working outside New York or London, if they are making work in Seoul or Shanghai or São Paulo, there is an expectation in the epicenter that you are speaking about or representing Korean or Chinese or Brazilian art. We wanted to fight against that.

Pilar: Los Angeles and Latin America are of course inherently linked, and the opportunity the initiative has provided in terms of its regional focus has been so significant. Yet our aim within the project is not to try to answer what constitutes Latin American or U.S. Latino art production, but rather to look at the work of artists who are defying categories at every step and seeing what we can learn from their practices.

What’s interesting about this show is that the artists were invited to do a residency to create works expressly for the exhibition. Can you tell us more about that?

Pilar: When we began this project many years ago, I was director of residency programs at 18th Street Arts Center and had been working closely with artists from all over the world using this model. Artists need time, space, and support to do what they do. We wanted to see what could happen when we paired a small institution that works with artists very intimately with a large-scale institution that can support more ambitious endeavors.

Rita: And that’s how we conceived of the show, with the residency in mind. We knew it would be process based. So the show doesn’t begin this week and run through February 19. Rather, the show began two or three years ago, when we started the process of talking with the artists and they started their residencies. The exhibition constitutes that time and continues to unfold during the run of the show.

José Luis: We didn’t have a checklist or selected objects. We just had a list of artists whose works and different processes were interesting to us. For a couple of years, we had to deal with the uncertainty of what the actual work in the show would be. That was exciting but also nerve-racking, and I had a hard time talking about it every time someone asked about the “look” of the exhibition. In that sense, we only had intuitions and premonitions as we continued our conversations with the artists.

What does the title “A Universal History of Infamy” refer to, and how does it touch on the spirit of the show?

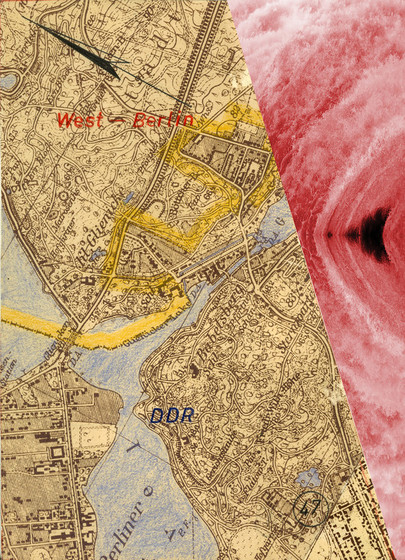

José Luis: “A Universal History of Infamy” is Jorge Luis Borges’s first collection of short stories. We were interested in how he “steals” entire tales and stories from the universal tradition while fusing them to the vernacular, altering the context or swapping words to bomb the architecture of the text from the inside. This title came to serve as an organizing principle to put together all these disparate projects and practices in a seemingly cohesive way. It also allowed the word “infamy” to come into the conversation when questioning the relation between LA/LA.

At the beginning of the show, there is a work by Dolores Zinny that directly refers to Borges and his strategies in dealing with the “universal.” Zinny’s work consists of two small drawings of the Mississippi, like pages of a book, paired up with a paragraph describing the mud from the river filling the Gulf of Mexico. The paragraph in English is from Mark Twain’s Life in the Mississippi while the paragraph in Spanish is from Borges’s A Universal History of Infamy. These paragraphs are similar but Borges replaces the word “dissolution” for “expansion,” so instead of talking about an “extended land” he describes the constant dissolution of a fetid empire. In a way, artists in this exhibition are talking about the tension between expansion and dissolution, in formal, political, and even poetic terms.

As the curatorial vision continued to morph, did the artists’ projects change as well?

José Luis: Certainly. We went to Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s studio during his residency to get a sense of what he wanted to do. He was getting ready to pitch an idea but he accidentally opened the wrong file and we saw a black-and-white photograph that looked like documentation of a play. We asked him about it and he hesitated about answering in detail to our questions. “No, no, I’m not sure about that. That’s the Heart of the Scarecrow but I don’t want to focus on that right now.” He had that project on the back burner, and we encouraged him to develop it for the show, as it would dialogue with other theater-related projects we were considering. In the end he decided to embrace the project, and the installation/performance ended up as a co-production by LACMA and the São Paulo Biennial.

Rita: The project actually continues to unfold, because the version he did in Brazil will be very different from the version he’s going to do in L.A. Even the installation is different from a typical sculptural installation. During the run of the show, you’ll see sculptures, props, and costumes, but at different points in time they will get activated by performers. The idea that these things could be activated is throughout the exhibition in different ways.

Pilar: As you can see, we have had to be very open in terms of how we allow our curatorial framing to be informed by new directions that the artists pursue. While there are research areas that we knew aritsts were interested in, there has also been the need to maintain a certain flexibility that allows for projects to be shaped as they need to in order to allow for process. That isn’t always an easy thing to do, but we felt it was very important to allow for that dialogue.

The exhibition is presented across three sites; at LACMA, an encyclopedic museum, 18th Street Arts Center, an artist residency complex, and Charles White Elementary School, a school at which LACMA has been programming exhibitions with contemporary artists. How would you recommend experiencing all of the components?

José Luis: At LACMA, we commissioned projects specifically for the exhibition, with the only exception of Afterwards by Oscar Santillan. The LACMA exhibition is the largest of the three and it features new projects. Virtues of Disparities, a title also borrowed from Borges’s infamous book, is the exhibition we organized for the small gallery at 18th Street Arts Center. For that exhibition, we selected small-scale works that were dealing with notions of likeness and authenticity by the same artists we have at LACMA. It allows the audience to get a broader scope on the work of these artists. Although most of these works existed before the residencies began, it is a nice gesture to have the artists again inhabiting the space through their works.

Rita: And at Charles White, which opens in December, it’s a curatorial project by the artist and educator Vincent Ramos. For him, it was very much on his mind that the space is in an elementary school with young audiences, many of whom may be facing situations in their family life that are impacted by discourses about immigration. He’s also bringing in emerging artists to the conversation and dialoguing with some works in LACMA’s collection, which is consistent with how we have been operating in Charles White over the years. Actually, he’s in the next gallery, installing his work for the LACMA exhibition. Let’s go talk to him.

Hi, Vincent. Tell us a little bit about your Charles White project.

Vincent: The show at Charles White Elementary School (A Universal History of Infamy: Those of This America) is very much connected with the exhibition here at LACMA , and to the climate of the country right now in regards to race and class issues, specifically relating to the Mexican and Mexican American experience. For that show, I’ve selected all figurative-based works from a variety of individuals and historical timeframes, both from LACMA’s permanent collection and from a great group of contemporary artists with similar concerns and ideas. All of the work makes reference to the dual presence and absence of the body during a type of cultural and historical distress.

The school’s student body is predominantly Latino. This show is ultimately for them. I hope it will function like a giant mirror, that they see themselves within the work and are empowered by the experience.

![Vincent Ramos, RUINS OVER VISIONS OR SEARCHIN’ FOR MY LOST SHAKER OF SALT (ANTE DRAWING ROOM) (RUINAS SOBRE VISIONES O BUSCANDO MI SALERO PERDIDO [ANTECÁMARA DEL SALÓN]), 2017, detail, courtesy of the artist, art © Vincent Ramos, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA](/sites/default/files/attachments/AUHOI_01.jpg)

A Universal History of Infamy opens at LACMA on August 20. Member Previews are August 17–19. Join now to experience this exhibition before it opens to the public! A Universal History of Infamy is part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, a far-reaching and ambitious exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogues with Los Angeles.