Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics, now on view at LACMA through August 3, 2025, finds aesthetic connections among 60 artists working in Africa, Europe, and the Americas. The exhibition and its catalogue are among the first to examine nearly a quarter century of production by Black artists.

Curator Dhyandra Lawson asked four artists to respond to written questions about their work and the diasporic experiences they are connected to. The artists’ respective practices center on photography, the most pervasive mode of representation today. In this excerpt, Sammy Baloji reflects on his work Mémoire (2007), which is featured in the exhibition. The full interview can be found in the Imagining Black Diasporas exhibition catalogue.

Dhyandra Lawson: In your film titled Mémoire, you collaborated with choreographer Faustin Linyekula, who danced in copper mines in Katanga Province. Can you please describe your relationship to the mine depicted in Mémoire?

Sammy Baloji: That work is about the remains of the Gécamines factories in Lubumbashi. The city of Lubumbashi was built in 1910, and its urban planning was organized mainly around the mining activity operated by the colonial enterprise called Union Minière du Haut-Katanga [UMHK]. Following the independence of the country and the nationalization of companies operating on Congolese territory, the mining company was then called La Générale des Carrières de Mines [also known as Gécamines]. I was born in Lubumbashi, and these factories, even if I did not have access to them growing up, are important places in the economy and the national history of Congo. In other words, working with these places is to activate the personal and collective memory with regard to the political events, past and present, that have taken place in this territory.

DL: Was it your or Linyekula’s intention for his gestures to resist or transform the energy of the place?

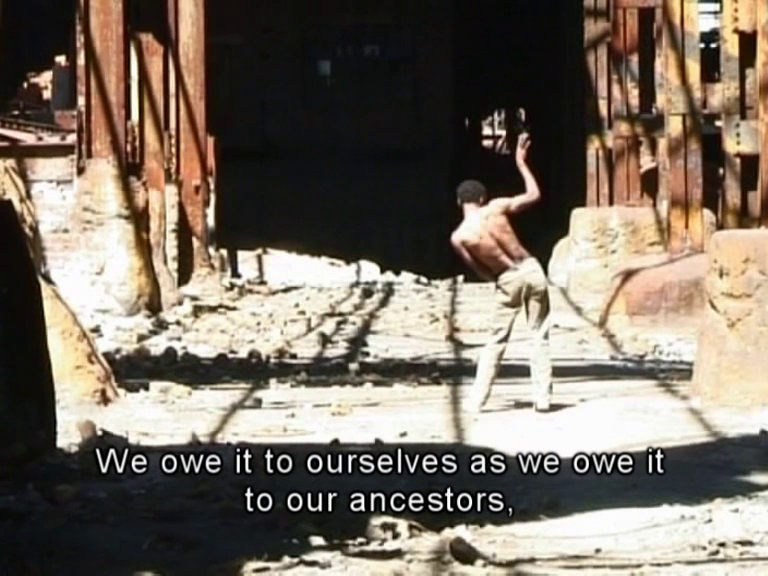

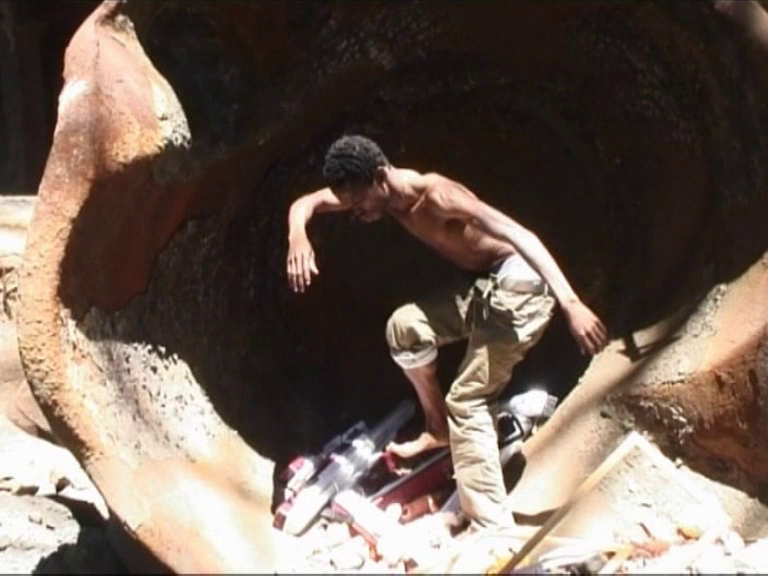

SB: For this film, I chose to work on the basis of fixed camera shots. This left room for Faustin’s body and choreography to be able to bring this ruined space to life. I wanted to work on the contrast between, in the background, rusty, stable, metal structures, pierced here and there by daylight, and, in the foreground, the body of Faustin, who, through his dance and his movements, creates scale and depth while summoning life—the simple life of a Congolese moving in light of political discourse, having gone through key moments in Congolese political history since its access to independence.

DL: You quote Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and a Pan-Africanist, in Mémoire. Lumumba has reemerged as a popular subject of discussion about Western intervention in the Global South. Have you observed whether Lumumba has inspired a contemporary movement in the Democratic Republic of Congo? How have younger generations interpreted his legacy?

SB: Lumumba’s story is just as dramatic as the advent of Congo’s independence in 1960, which only lasted a few days before the entire country burst into rebellion and secession wars, often based on ethnic claims. Ethnic identification in the Congo is a result of the Belgian colonial administration, which knew how to control and intervene in the traditional system of transfer of power and inheritance. On the eve of Congo’s independence, there were a very small number of Congolese intellectuals capable of taking over the management of the country. Technically, Lumumba did not have time to manage the country after independence. And his assassination by his Congolese counterparts was ordered between the Belgian and American secret services. Other than the speech given on June 30, 1960, Lumumba left very few pragmatic legacies. Representing his speech, Mémoire concretizes the ideals that he left behind, in the absence of their being exercised. The fact that Lumumba was martyred so soon leaves room for speculation and possible reappropriation of his speech. The political reality in which the country finds itself is often far removed from this discourse and its promises.

DL: You made Mémoire seventeen years ago. Reflecting on the piece now, how does the work resonate with you?

SB: I think that this work remains relevant, especially if we observe how the privatization of the mining sector in the southern provinces of Congo weakens the living conditions of Congolese. We can also observe the degradation and pollution of the environment following massive mining, the unemployment rate. However, the political environment has not improved. This raises questions about the future of the Congo.

DL: What is the significance of the work’s title, Mémoire?

SB: The significance of the title is just the definition of the word memory: the ability to store and recall things from the past and what is associated with them. This ability to store and recall can be selective. In short: we can try to forget just as we can try to remember.