On January 27, LACMA’s satellite gallery at Charles White Elementary School reopened to the public with a new exhibition, A Universal History of Infamy: Those of This America. With generous support from the Los Angeles County Quality and Productivity Commission through the Productivity Investment Fund, LACMA has made physical improvements to the space to allow for greater community access. The renovated space is now open to the public every Saturday afternoon, with programming generously supported by United Airlines. Part of the multi-site project A Universal History of Infamy, Those of This America was curated by artist and educator Vincent Ramos to explore the use of art as a powerful method of resistance. Last fall, I sat down with Vincent to learn more about his inspirations and motivations.

You have lived and worked in Los Angeles your whole life. What were some of your early experiences with art in the city?

Growing up in Venice, art was kind of everywhere, especially in the murals I remember from my youth. A few remain but most are gone. Many dealt with social or cultural issues dating from the early 1970s, so there was always a message behind them. Graffiti was everywhere in Venice too. Gang graffiti, political graffiti. A literal writing on the wall. My dad painted at home in his free time during my childhood and that was very influential to me. In high school, I had an art teacher named Marco Elliott who was an early mentor. Through his class, I saw a handful of shows that, in retrospect, were important touchstones. Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation (1990) and A Different War: Vietnam in Art (1991), both at UCLA, were among them. After high school, Marco connected me with the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) in Venice. They were just beginning a new youth program with CalArts called Community Arts Partnership (CAP). Through that program I met many artists, including Salomón Huerta, Rubén Ortiz-Torres, Sandra de la Loza, Luis Jiménez, Eva Cockcroft, David Avalos, Karen Atkinson, Richard Wyatt, and of course Judy Baca, who co-founded SPARC.

I had just begun driving at this time, so I was able to see things outside of my immediate community as well. I frequented the Lannan Foundation, where I saw some great shows like an incredible Robert Frank retrospective and an early Gary Simmons show. Around this same time I saw Mike Kelley lecture at SCI-Arc, when it was located in Culver City. That was pretty close to life-changing. Helter Skelter at MOCA. The original LACE downtown. The old Self Help Graphics under the direction of Sister Karen. The murals of East L.A. The Degenerate Art show at LACMA. All new to me. Everything floored me. An intense education to say the least.

You’re talking about the seminal exhibition “Degenerate Art”: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany (1991), which explored the 1937 exhibition by Nazis that attacked modernist art.

Yes, that show introduced me to German Expressionism, which had a profound impact on me. My grandfather was a World War II veteran, so I always had an interest in that moment. To see the actual art up close and to get the historical context as well was immensely important. That experience and its influence have never left me.

A few years later I actually worked at LACMA as a museum guard. The first exhibition I worked on was a David Hockney drawing survey. I remember working a great Roy DeCarava show and a William Burroughs show that was really influential to me. That was over 20 years ago, when the employee parking lot was where BCAM now stands and the guards wore ugly forest green polyester blazers.

.jpg)

In your work, you look at the present through the lens of the past. Have you always been interested in history, whether global, local, or personal?

Absolutely. As a kid, I used to love hearing the bits and pieces of stories and memories my grandparents would share with us. They were all great storytellers. They had a certain dry humor that was representative of the sometimes difficult lives they endured as Mexican Americans in this country during the early and mid-20th century. With this said, it was always peppered with more humor than sadness, more good times than bad. At least that’s the way I remember it. My love of the city begins with their histories as they spent their adult lives contributing to the long-term success of this place in myriad ways, mostly through their individual hard work, both the men and the women in my family. I drive through Venice today and still feel their presence.

The same for my parents; they came of age in the ’50s and cut their teeth here as a young married couple in the tumultuous 1960s. My dad was stationed in Berlin at the height of the Cold War, saw the Berlin Wall being built. I had five uncles in Vietnam. My dad’s brother was killed there during the summer of 1967, the so-called Summer of Love. Less than two years later, his youngest brother was there too. He survived but it haunted him for the rest of his life. I’ve made work about many of their experiences and will continue to, as I feel that, in doing so, it force-feeds an alternative narrative of America that doesn’t exist outside our own communities. It is especially important in this day and age to remind people of past lives, with ignorance and narrow-mindedness running rampant and the spewing of revisionist history at an all-time high. I need the voices of my elders now more than ever. Many of us do.

How has the current moment influenced your approach for the exhibition at Charles White Elementary School?

This show comes directly out of this moment. It comes out of the 2016 election and its fallout. I’m an art teacher at an elementary school, and in retrospect, my kids there were the real impetus for this project. In the days after the election, I was talking to some of my Latino students, trying to get a sense of how they felt. If you remember, there was a lot of talk about how children, especially children of color, were especially freaked out as a result of Trump being elected. So I remember trying to ease into a conversation with a few third graders, thinking they’re really afraid about the future. I quickly learned that there was not an ounce of fear in these children. They were so steely-eyed in their approach to dismissing him and his fear-mongering that all they could do was crack jokes about him and laugh uncontrollably. They already knew his promises were empty. They knew before I knew. I thought I would assure them and they ended up assuring me. It was beautiful. I’m assuming that their peers at Charles White are cut from the same fearless cloth. As a result, this show is custom-made for them.

How did that feeling of resistance and resilience manifest in Those of This America?

Early on, I made the decision to make it a primarily figurative show. I was thinking about artists who have been very important to me through the years, individuals who have utilized the figure to comment on their respective eras, especially in relation to politics. Artists like Leon Golub and Nancy Spero. This led me to thinking about how a show like this would look through the lens of the brown body, as both creator and subject. I became interested in this notion of a dual presence and absence during times of social turmoil, as it related to the Mexican and Chicano experience in this country—a substantial portion of which used to be Mexico. So a lot of the work talks about these ideas; about layers of erased histories, about non-existent or fluid borders.

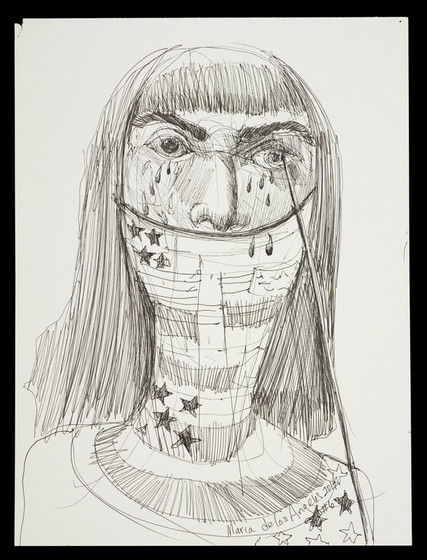

There are a few artists in the show I’ve had ongoing dialogue with for quite some time now, people like Victor Estrada, Patricia Valencia, Jorge Orozco Gonzalez, Isabel Avila. I’ve only recently become aware of others, like Maria de Los Angeles, Teresita de la Torre, Yvette Mayorga. The works borrowed from LACMA’s collection run the historical gamut, from ancient times to today. It should also be mentioned that there are other cultural voices present in the show as well. There are contributions from Native American artists, like the late Fritz Scholder, as well as two non-Latino artists directly from the 20th-century art historical canon, Philip Guston and Peter Saul. All of the artists, regardless of their specific cultural background, have been fearless in their approach to commenting on their respective times. That is ultimately where their connectivity lies.

I also invited some equally powerful writers to participate. They were asked to respond to select works within the exhibition. Sesshu Foster, an established poet, whose book, City Terrace Field Manual, was very important to me as a young person. And Carribean Fragoza, Rocío Carlos, and Stephanie Guerrero. They are all Los Angeles natives and understand the city and its working-class peoples and neighborhoods in a very intimate, unique, and dynamic way. The show and the community will no doubt benefit from their collective voices.

Can you talk about the importance of representation in art?

I have never not been aware that culturally I am everywhere and nowhere. What I mean by this is that our contribution to history, specifically the history of this country, is abundant, but you would never know that by what and who is included in our history books, or by positive representations in popular culture, or by whose life’s work is wholly embraced and collected by the majority of our most important museums and other cultural institutions. So this invisibility is, in many ways, our actual presence. People of color exist in this country as ghost cultures or footnote cultures. That is fact. That’s why the Getty PST: LA/LA initiative is so important to the possibility of rewriting history and being more inclusive to a much larger, more complex art historical narrative. I don’t know whether this will actually occur and remain in the long term. I tend to be pessimistic when it comes to things like this. I came to the realization early on that blatant forms of tokenism are as American as apple pie.

.jpg)

What do you hope the kids will take away from the show?

At the end of the day, I want the students to see themselves within this work. If they see themselves, they walk away from the exhibition potentially empowered, and this, from my own experience, stays with them long after the show is over. It can literally stay with them for a lifetime. Art has this ability. I know this. You know this. But they may not yet know this. That is the ultimate goal. There is so much negativity and baseless rhetoric as of late, much of it aimed directly at these kids. This show could be an alternative to that, a small gesture that functions as the flip side to the current chaos that they, like the rest of us, are currently left to endure.

Vincent Ramos (b. 1973) received his MFA from the California Institute of the Arts (2007) and his BFA from Otis College of Art and Design (2002). Recent exhibitions include The Parable of Arable Land, If I Had a Hammer, The Wilhelm Scream, Conduit, Dallas (2015); Plum Pudding Peanut Island (Gilligan’s Squaw Fire Island II), Elephant, Los Angeles (2013); In the Good Name of the Company, See Me Gallery, New York (2013); Made in L.A. 2012, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2012); Pachuco Cadaver or There Are No Heavies in America, Las Cienegas Projects, Los Angeles (2011); and Outsider Art: Others from Elsewhere Doing Something Altogether Different… Sort Of, 18th Street Art Center, Santa Monica (2011). He lives and works in Venice, CA. A Universal History of Infamy: Those of This America is on view at Charles White Elementary School through October 6.