“Yampolsky” isn’t exactly a name one would immediately associate with Mexican art. Yet, Mariana Yampolsky (1925–2002), a photographer and printmaker born in Illinois, became an unexpectedly influential figure in modern Mexican cultural history when she joined the artist printmaking collective the Taller de Gráfica Popular (The People’s Print Workshop) in Mexico City. Despite her migratory background, however, Yampolsky is rarely described as an “immigrant,” but rather as an “émigré” or “expatriate,” raising questions as to the definitions of each. A current exhibition at Vincent Price Art Museum (VPAM), Mariana Yampolsky: Photographs from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, identifies Yampolsky as a nuanced figure in the history of cultural dialogue between Mexico and the U.S. Additionally, the concurrent juxtaposition of Yampolsky’s work with an exhibition of more contemporary photography at VPAM, Rafael Cardenas: Backyard Tableaux, invites us to reconsider the role of race and ethnicity in deciding who qualifies as an immigrant and who qualifies as an émigré.

.jpg)

The daughter of upper-class Russian-Jewish immigrants, Yampolsky found herself somewhat of an outcast growing up in rural Illinois. Yampolsky yearned to leave the United States upon graduating from the University of Chicago and immigrated to Mexico City at the tender age of 19. Her move was motivated in part by the allure of post-revolutionary Mexican culture, but also by the rise of anti-Semitic sentiment in the U.S. and Europe in the 1930-40s. It is these “push-and-pull” factors on both sides of the U.S.-Mexican border that make Yampolsky a complex figure in the cultural exchange between these two countries. Yet, Yampolsky and other prominent émigré figures in Mexican art, like Ed Weston and Tina Modotti for instance, are hardly ever referred to as “immigrants” in art historical scholarship, and escape the sometimes negative connotations of the term. Though a seemingly arbitrary difference in terminology, these euphemistic labels actually insulate wealthy white or “white-passing” émigrés and expats from the public derision that faces black and brown migrants. Undoubtedly, this inconsistency in terminology unfairly affects how these two different groups of immigrants are perceived and treated by society at large, and we must take this into account as we revisit the various émigré figures in Mexican modernism, including Yampolsky.

Whether Yampolsky is an immigrant or an émigré is not a question meant to discredit her artistic contributions, but rather, to reframe them in the context of immigration. Her work with the Taller de Grafica Popular, of which she was the only female member when she joined in 1945, attests to her ability to cross cultural and gender lines. It is rarely considered, however, that her ease in crossing these boundaries is perhaps due to her unique position as an outsider to Mexican culture. It may be that Yampolsky’s status as an immigrant from outside Mexican culture exempted her from the gender roles imposed on Mexican women at the time. This outsider status may have allowed her to emerge as a leader of the Taller, curating exhibitions while also actively contributing to the collective as an artist.

With this positionality in mind, Yampolsky made a point of immersing herself in Mexican culture, and dedicated her life to her chosen home until she died in Mexico City in 2002. She became a Mexican citizen, and committed herself to raising social consciousness through printmaking at first, and later, through photography. “I can’t conceive of art without a social context,” Yampolsky related to art historian Shifra Goldman in an interview, emphasizing that “it’s not just what you as an individual want to express; it must be understandable by others.”* It was this interest in creating accessible art for public consumption that influenced Yampolsky’s transition from printmaking to photography, as she began to see the technical process of printmaking as too elitist.

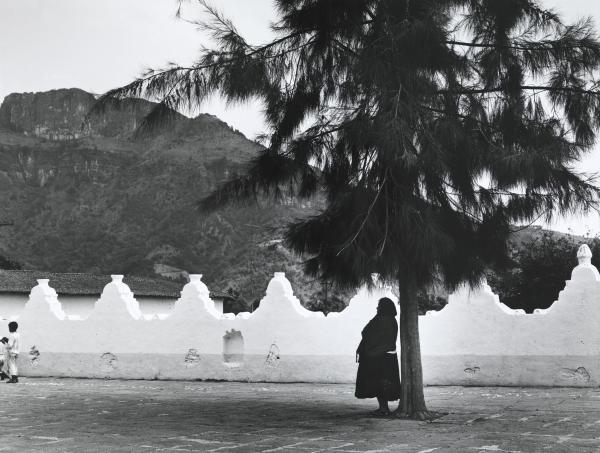

Under the mentorship of noted photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo at the San Carlos Academy, Yampolsky began to photograph the activities of the Taller de Grafica Popular, but soon turned her attention to capturing portraits of the indigenous people of Mexico. Centering indigenous people was a radical act in a Post-revolutionary Mexican society that was reclaiming indigeneity as part of Mexican culture, yet still turning a blind eye to the injustices that continued to marginalize indigenous people. Photographs like Cinco Danzantes de la Sierra de la Puebla celebrate the rituals, gatherings, and labor of the people Yampolsky interacted with, and all accounts paint her as a gracious outsider. Rather than objectify the people she met, she respectfully asked for their consent to be photographed, and was known to freely give prints of her work to her subjects. Perhaps due to her own experience as the daughter of Jewish immigrants coming of age at a time of pronounced anti-Semitism, Yampolsky understood the importance of humanizing people often relegated to the margins of society.

In addition to portraiture, Yampolsky took a special interest in indigenous art and artisanal craftwork, and photographs like Piñatas Apiladas, San Juanico (Stacked Piñatas, San Juanico) document their wares and everyday cultural artifacts.

A concurrent exhibition at VPAM, Rafael Cardenas: Backyard Tableaux, serves as a contemporary counterpoint to Yampolsky’s work. Photographer Rafael Cardenas documents his community from a perspective quite opposite from Yampolsky’s, yet there is an observable affinity between the two artists. Like Yampolsky, Rafael Cardenas found his artistic voice in a chosen home abroad. Born in Jalisco, Mexico, Cardenas moved to California and immersed himself in the predominantly Latinx cultural landscape of East Los Angeles, taking theater and design classes at East Los Angeles College before turning to photography. Unlike Yampolsky, however, Cardenas shares a cultural heritage with the people he captures, and offers an insider’s perspective to the scenes he captures.

Photographing everything from protests to parties, Cardenas is an integral figure to the community he documents. He expresses a social interest and personal investment in rendering marginalized communities visible to a wider audience.

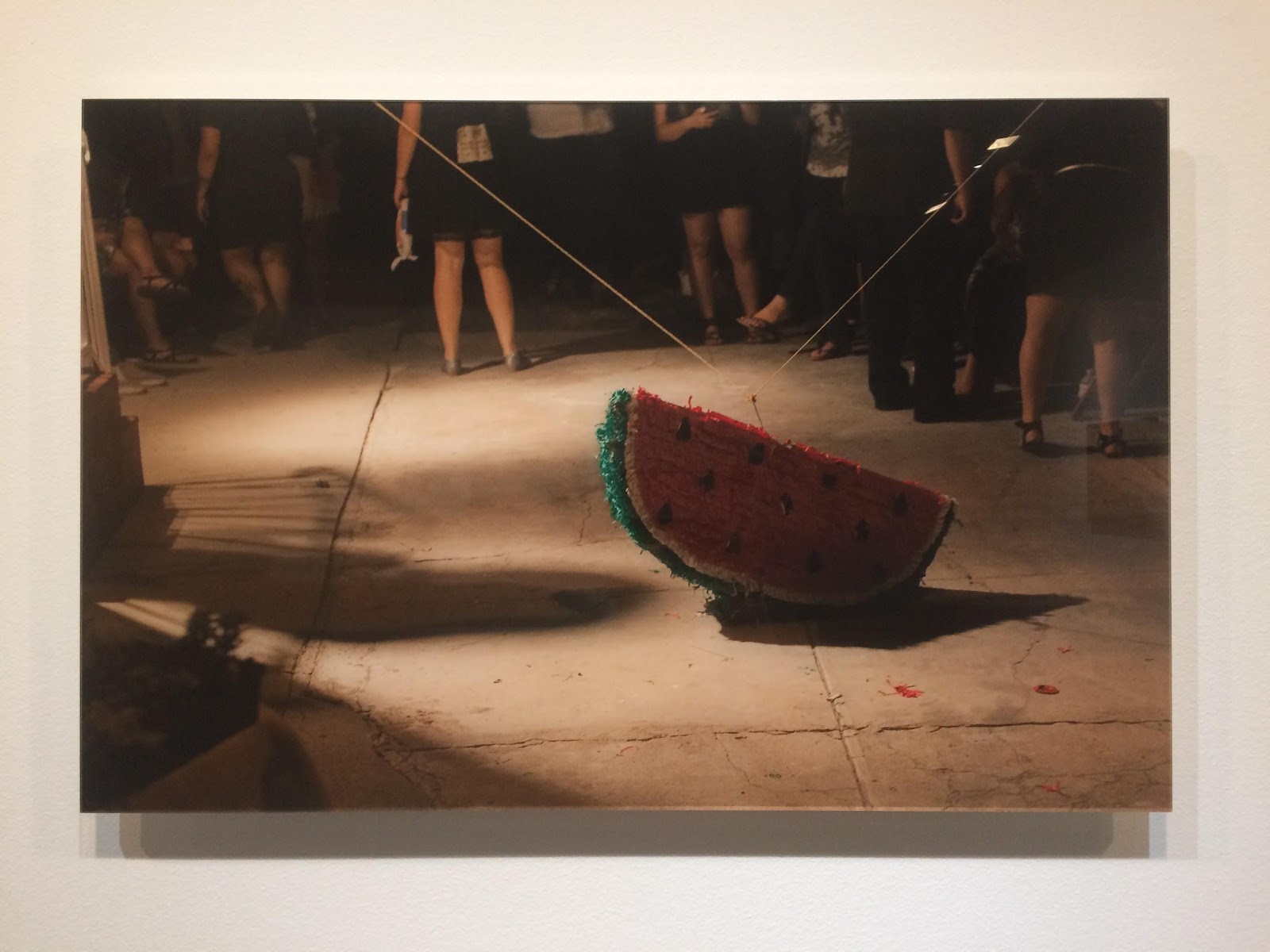

Cardenas’s newest body of work, Backyard Tableaux, is an ongoing series in which the artist turns his attention from the public realm to the private, achieving striking similarities to Yampolsky’s work while offering a contrasting perspective. A series of full color photographs reproduced on semi-transparent Plexiglas, Backyard Tableaux is a departure from Cardenas’s work in black and white, yet still reflects his singular connection to the people he photographs.

The interplay between public and private spaces can be seen in both artists’ works, specifically in Yampolsky’s El Almuerzo, Hacienda Tepetates, Tlaxcala (The Lunch, Hacienda Tepetates, Tlaxcala), and Cardenas’s Pour Me One. Both photographers captured a subject in a different room, yet the result of Cardenas’s work achieves an invitational quality, while the Yampolsky photograph emphasizes the perspective of being on the outside looking in (both literally and figuratively). In addition to powerful portraiture, there is also commonality within the artifacts that Yampolsky and Cardenas choose to document.

For instance, Cardenas’s Pendulous is reminiscent of Yampolsky’s Piñatas Apiladas, discussed above, and captures a familiar cultural artifact in the East L.A. community, but achieves a participatory, rather than documentarian, effect. Also like Yampolsky, who went on to produce art and history textbooks for Mexican primary schools in her later years, Cardenas’s social practice extends to the classroom. Leading photography workshops with organizations like Las Fotos Project and LA CAUSA Youthbuild, Cardenas been able to turn his creative expression into a powerful educational tool for social change.

The concurrent Yampolsky and Cardenas exhibitions at Vincent Price Art Museum offers fertile ground for conversations surrounding immigration and its influence on art and culture. In an upcoming talk on June 28 at VPAM, Approaching the Everyday: Rafael Cardenas, Mariana Yampolsky, and Photography, curator Eve Schillo and Cardenas will discuss these shared nuances between the two artists’ work, extracting the similarities and differences in their experiences while challenging the greater audience to reconsider the relationship between migratory experiences, creative expression, and resulting historical narratives.

* Goldman, Shifra M. “Six Women Artists of Mexico.” Woman's Art Journal, vol. 3, no. 2, 1982, pp. 1–9.