When the Pavilion for Japanese Art—conceived by collector Joe Price and designed by architect Bruce Goff—opened to the public in 1988, it was lauded as an architectural success. Its use of Kalwall to mimic the translucency of Japanese shoji panels allows for the viewing of Japanese scrolls, screens, and objects under natural light conditions. Now entering its 30th year, the building has started to show its age and is due for a retrofit and wholesale maintenance mostly of its structural, mechanical, and electrical systems.

The vault in the Pavilion held nearly 5,000 Japanese objects, paintings, and works on paper. As the two-year retrofit requires all climate control systems be shut down, the art had to be moved to a stable storage environment. The Collections Management department, aka PACMA, therefore planned integration of the Japanese collection into a storage area with other curatorial departments.

Unique to the Asian art collections at LACMA are the hanging scroll, handscroll, and standing screen formats, which account for roughly 475 Japanese art objects—350 scrolls and 125 screens. Thankfully, their compact nature allows for a comparably small storage footprint to paintings of similar size in other departmental collections—a 10-foot-wide screen painting can fold to occupy a five-inch space. Likewise, a 30-foot handscroll can roll to a three-inch diameter. Because they are mainly made of silk and/or paper, these mediums are sensitive to changes in the environment and thus require a specific manner of handling. Inherent to screen design is the tautness of paper or silk stretched over a framework which, if allowed to become too dry, will burst and tear, which means it is important to find a space where relative humidity (RH) and temperature could be monitored. To prepare, we designed and constructed a series of tall bins which could accommodate the screen collection, using conservation-approved materials.

Over several months, members of the PACMA team deinstalled objects on display in the west wing, retrofitting existing containers for transportation and constructing new containers for objects without them. We did the same for objects in the Pavilion vault. Wooden scroll boxes, which themselves can be considered art objects due to object-relevant inscriptions, were also given slipcovers.

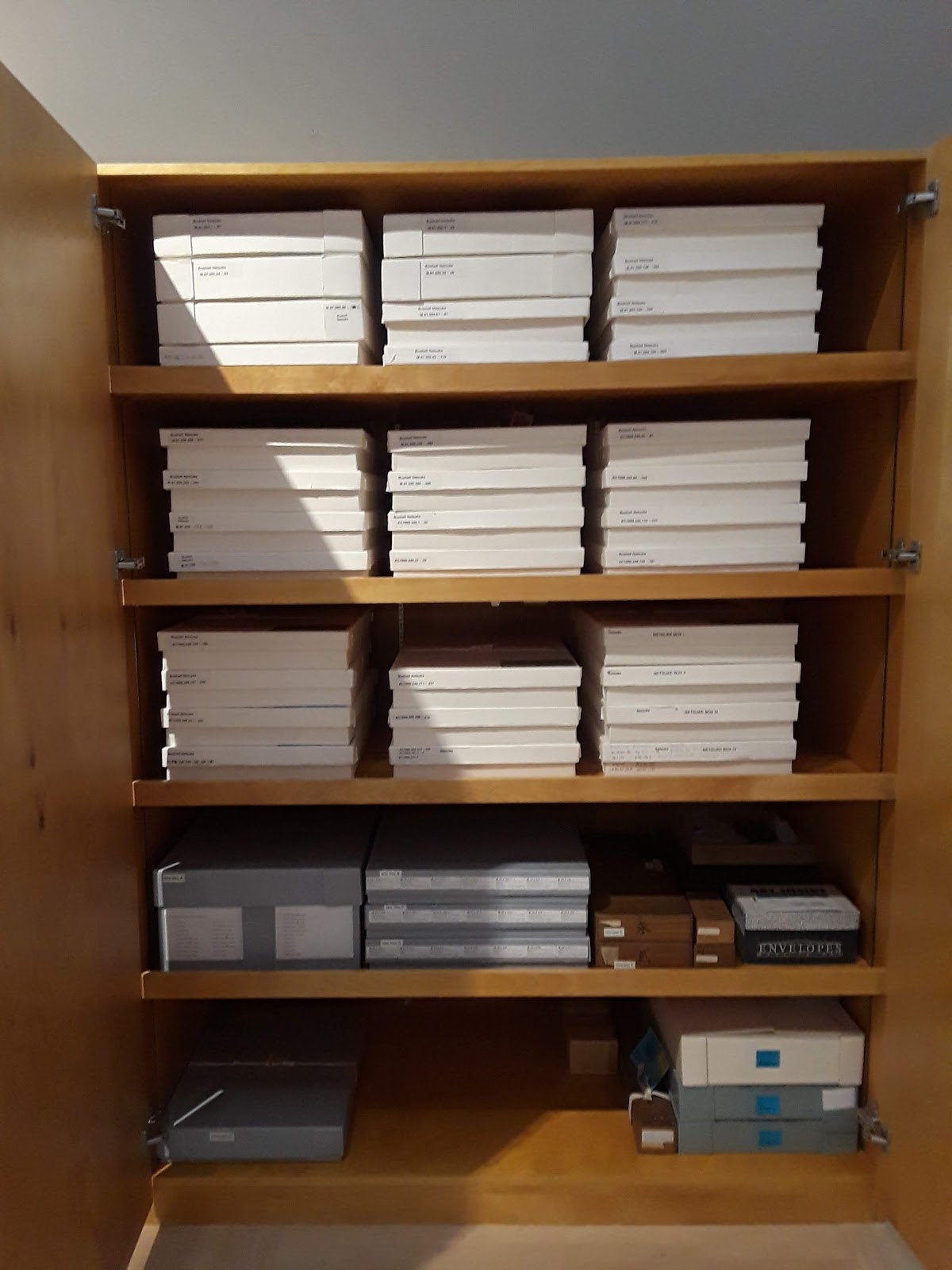

When the gallery and vault packing project was completed, PACMA, with the assistance of a Collections Management intern, moved everything into the prepared storage space. The works on paper, stored in solander boxes and flat files, had been organized in the vault first by chronology, then by artist or artist family, and then by series—this order was maintained in the new space. Three-dimensional objects were moved from the galleries and vault, then shelved according to museum number designation. Two PACMA personnel worked with the curator of Japanese art to organize the 230 permanent collection scrolls into groups based on their subject matter, school, or style, such as Buddhist/Shinto, Maruyama-Shijo, and Nanga. We also transported miniature sculptures known as netsuke in padded boxes stacked inside locked rolling cabinets.

On a more personal note, it has been a pleasure and privilege to serve a pivotal role in the relocation of such outstanding artworks. Through this experience, I have not only found new avenues of research—such as the organization and usage of Buddhist mandalas—but have also had the unique opportunity to closely admire pieces I have seen (and thought I would only see) in textbooks. My role as an Asian art collections specialist has allowed me to train on proper handling with Conservation department personnel, and in turn to teach the proper techniques to other PACMA members.

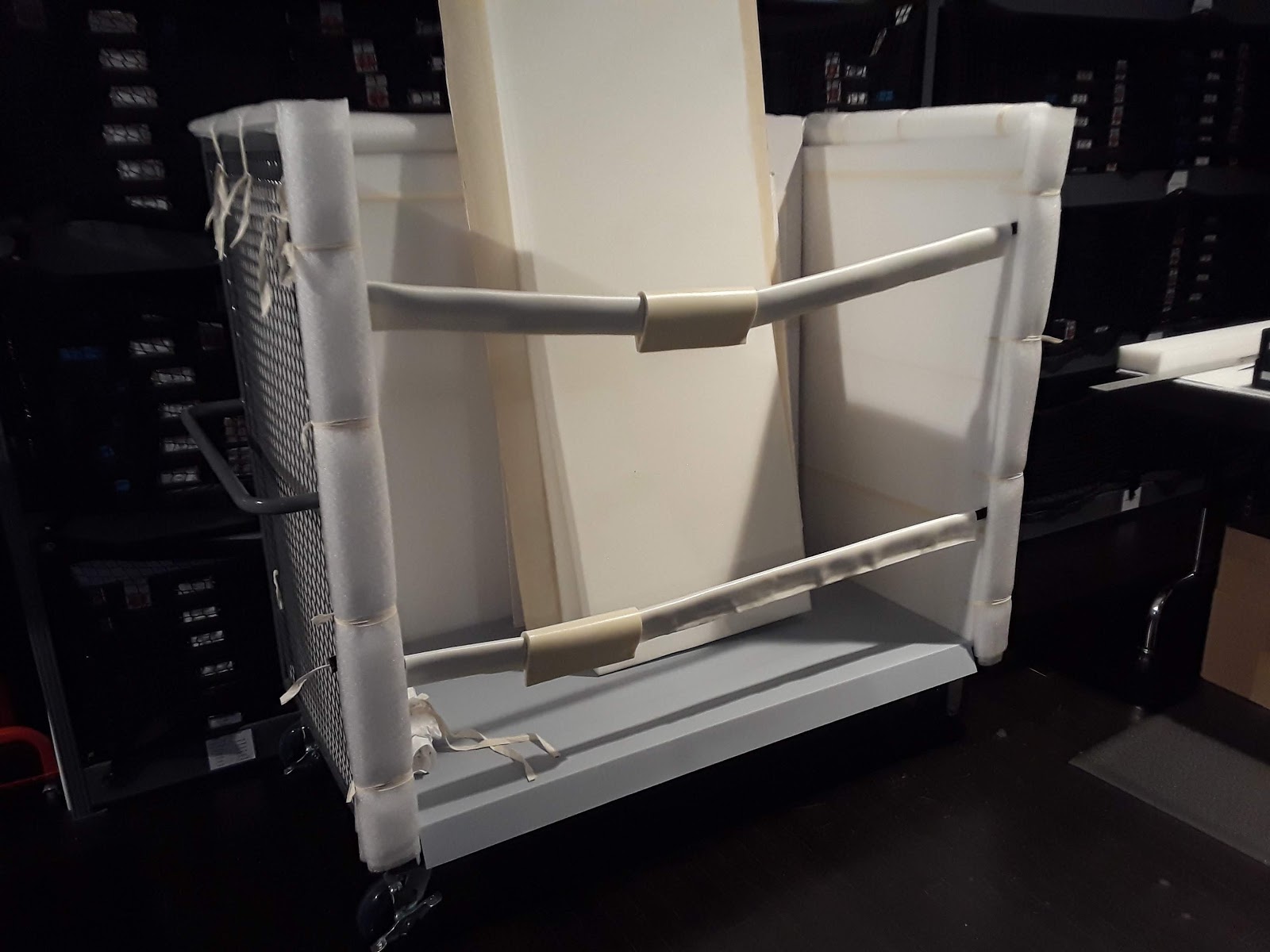

We were collectively able to troubleshoot issues of the move, the most pressing of which was how to move 65 screens with one purpose-built cart that had a total capacity of four screens. After some deliberation, the PACMA team purchased a metal frame cart and retrofitted it with museum-grade ethafoam, volara, and earthquake strapping to make a stable and secure vehicle with an additional capacity of 11 screens. Needless to say, we made much quicker work of moving the screens than we had initially planned.

Through tireless effort and a keen eye to detail and object safety, the PACMA team successfully moved artworks out of the storage spaces and galleries in the Pavilion for Japanese Art. We look forward to the day when it will once again showcase LACMA’s impressive collection of Japanese art objects.