Detailed examination of George Bellows’s Why Don’t They Go to the Country (for a Vacation)? from LACMA’s permanent collection revealed that the previous media identification of “transfer lithograph” was incorrect, leading to further investigation into determining its true printing process. Through collaboration between conservators, curators, and scientists between three different Los Angeles museums, the previous “transfer drawing” identification was confirmed, but it was discovered to be a unique type of transfer drawing called a “direct trace monotype” that uses printing ink in a hybrid between a print and a drawing.

Our journey from one media identification to another involved connoisseurship, scientific analysis, microscopic examination, and the creation of many mock-ups, which we will focus on today.

INVESTIGATION OF TRANSFER DRAWING TECHNIQUES

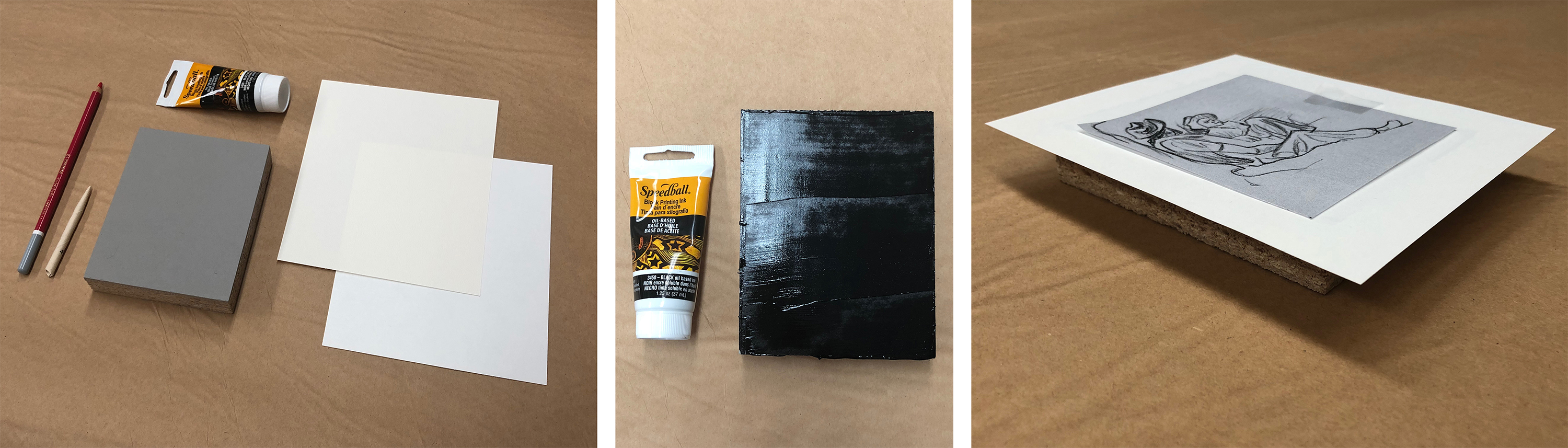

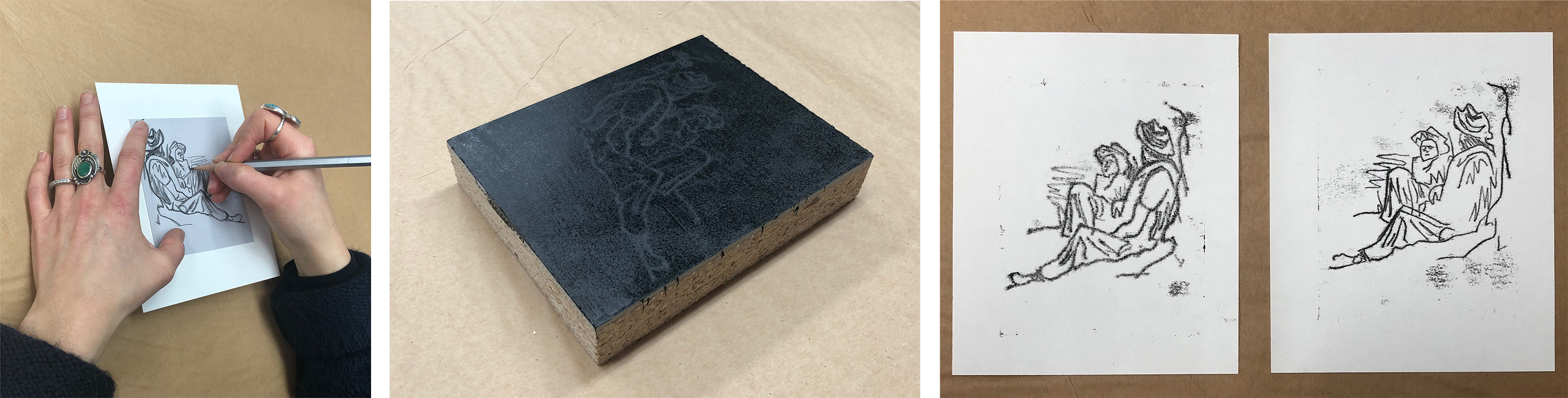

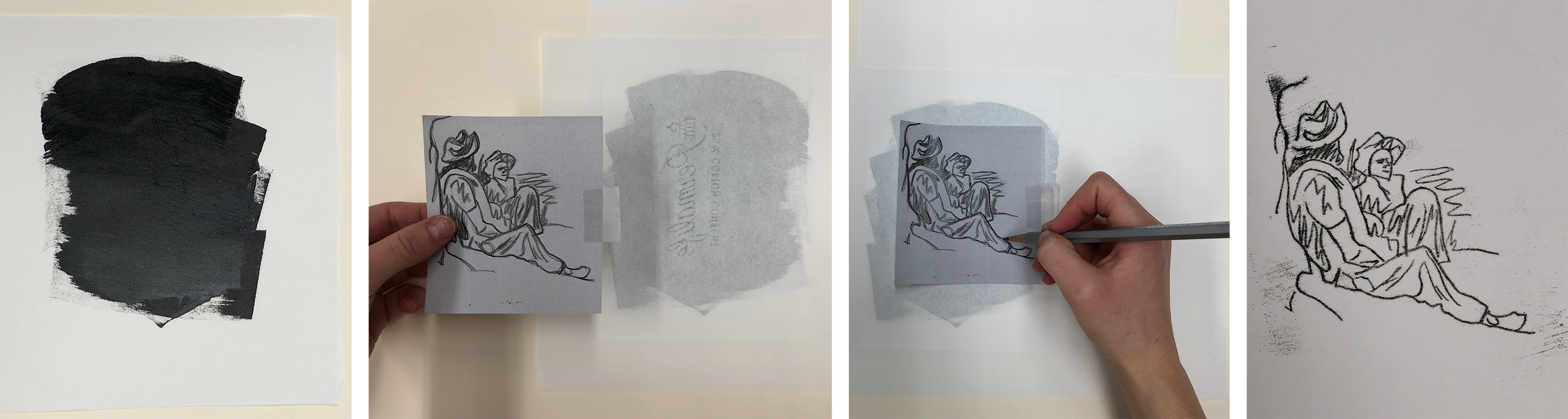

Making mock-ups of materials and techniques is often incredibly helpful in determining how or with what an object in question is made. I set about replicating various iterations of the direct-trace monotype process, including using Gauguin’s oil transfer drawing technique and using both hard and soft ink matrices.

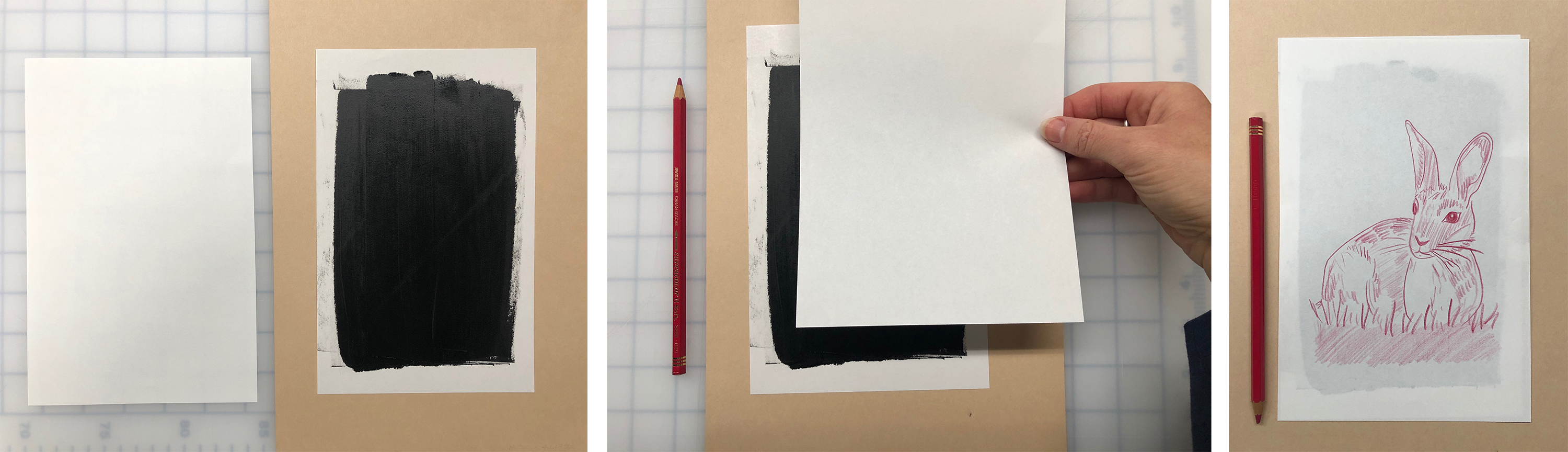

Oil Transfer Drawing

Paul Gauguin wrote to his patron Gustave Fayet in March 1902 describing an experimental new technique he had discovered: a hybrid between a drawing and a print that created unique images, rather than multiples like a true print is capable of. These “oil transfer drawings,” as he called them, were created as such: “First you roll out printer’s ink on a sheet of paper of any sort; then lay a second sheet on top of it and draw whatever pleases you. The harder and thinner your pencil (as well as your paper), the finer will be the resulting line.” This technique creates a two-sided artwork, with the final image rendered in printing ink on one side and drawing media (graphite or similar) on the other, mirror images of one another.

While the Bellows work closely resembles the Gauguin oil transfer process, it is not double-sided. This indicates that an intermediary paper was used to trace the composition upon. Prints like this can be created using either a hard or soft matrix to hold the printing ink, with a fully prepared drawing or scrap paper placed atop the paper to be inked to trace the image, leaving no drawing media on the final paper itself, only printing ink.

Hard matrix direct-trace monotype

Using a plate of glass, linoleum block, or simply a worktable surface is a great way to create a hard matrix with which to carry the printing ink necessary for a direct-trace monotype. The image is created in the same way, with the hard matrix carrying the ink that is transferred to the final paper using a stylus. The resulting image is a mirror image of the preparatory drawing.

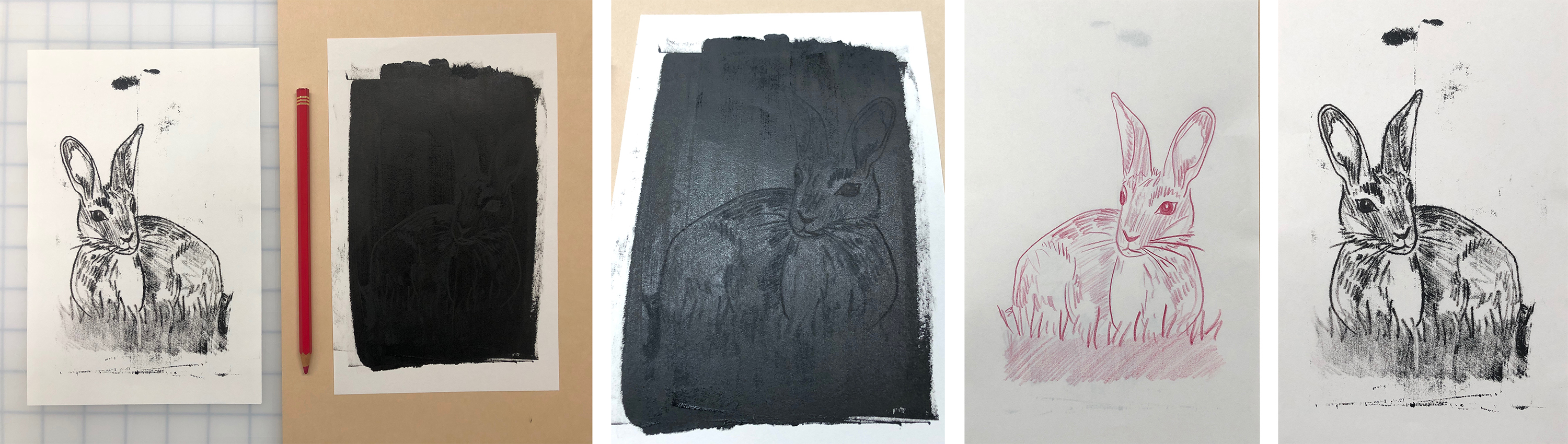

Soft matrix direct-trace monotype

-2-3.jpg)

Inked paper is similar to carbon copy paper, and aligns somewhat more closely with what we think of as a transfer drawing. But rather than transferring a dry carbon or dye-based pigment, this technique deposits oil-based printing ink to the final paper. The final image can be identical or a mirror image of the preparatory drawing based on the orientation of the inked paper matrix. This is most likely the technique that Bellows used for this artwork, based on a number of indications like the patchwork appearance of the light and dark black areas in the top right quadrant and the presence of a countermark from the intermediate paper matrix as well. My tests indicated that transferring the faint impression of a watermark was indeed possible in this technique!

WHAT’S NEXT?

With all of this examination, scientific analysis, and printmaking practice, the Bellows artwork now has a different media identification to be used in future exhibitions and catalogues. Rather than the inherited description as a “transfer lithograph,” the work will be henceforth referred to as a “transfer drawing” or “direct-trace monotype.” This more accurate description is critical not only to understanding how the piece is made but what the artist’s practice was in bringing to life his vision of the composition. Moreover, the fact that this work is not a lithograph, of which hundreds of copies could be made, but is made directly from the artist’s hand, means that it is truly one-of-a-kind.

This fascinating artwork is currently on display at the Getty, one of many LACMA prints that are part of the True Grit exhibition on view through January 19, 2020. Visit the work to discover its secrets for yourself!

Further reading:

2012. “George Bellows.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Exhibition catalogue: Brock, C. et al. 2012. George Bellows. Washington: National Gallery of Art.

Kimmelman, M. 1992. “ART VIEW; George Bellows, Iconoclast with a Heart.” The New York Times.

Johnson, L. 2014. “Metamorphosis: Paul Gauguin’s Oil Transfer Drawings.” Inside Out: A MoMA/MoMA PS1 Blog.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art. 2019. Why Don’t They Go to the Country (for a Vacation)? LACMA Collections entry.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art. 2019. Cliff Dwellers. LACMA Collections entry.

![Getty curators Stephanie Schrader and Edina Adam, Getty conservator Michelle Sullivan, and former LACMA (now Getty) curator Naoko Takahatake examine the Gauguin “oil transfer drawing,” image courtesy of Madison Brockman. Foreground: Paul Gauguin, Eve ['The Nightmare'] (recto); Eve ['The Nightmare'] (verso), c. 1899–1900, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Background: William Blake, Satan Exulting over Eve (detail), 1795, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles](https://unframed.lacma.org/sites/default/files/styles/article_full/public/field/image/IMG-0064.JPG?itok=SlJ0culR)