LACMA’s recent exhibition Betye Saar: Call and Response offered a rare insight into the artist’s sketchbook practice. Sketchbooks appear occasionally in exhibitions—usually as comparative or secondary material—but rarely do they feature prominently as the focus of an exhibition. For those interested in the artistic process, sketchbooks can reveal the artist’s initial spark of inspiration and early meanderings, including mistakes and accidents which, in some cases, turn out not to be mistakes at all but open up new possibilities. The sketchbook is small and intimate and private, like a journal. Its informality allows for impromptu and open-ended exploration, and its portability makes it readily available to capture an idea or an image, whenever or wherever.

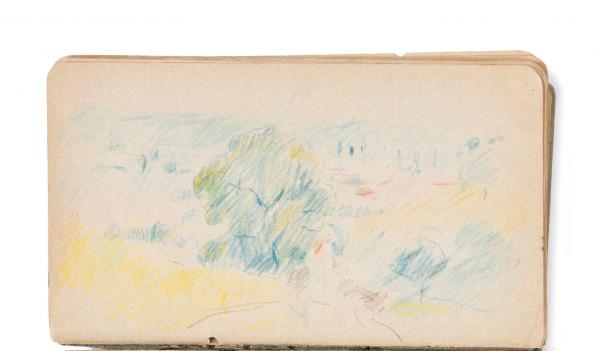

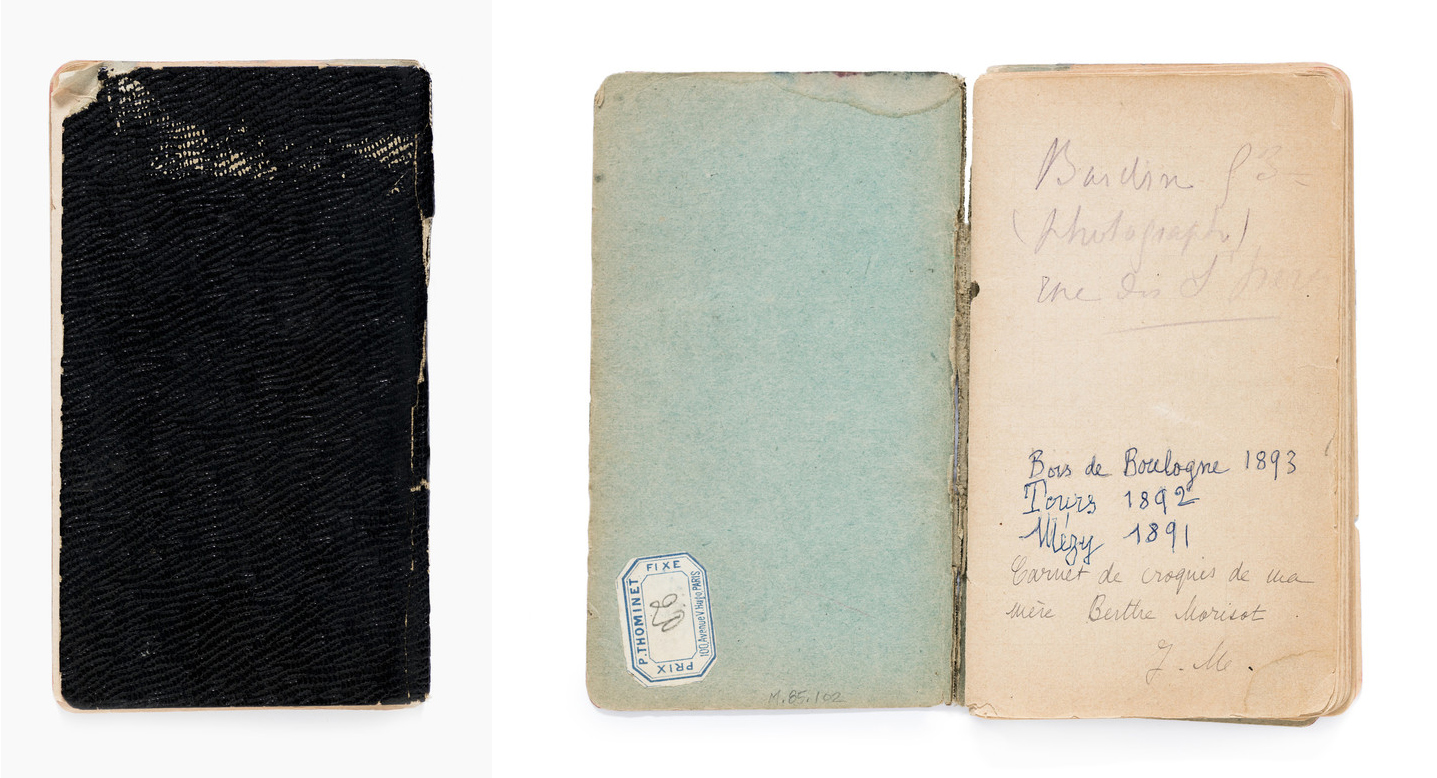

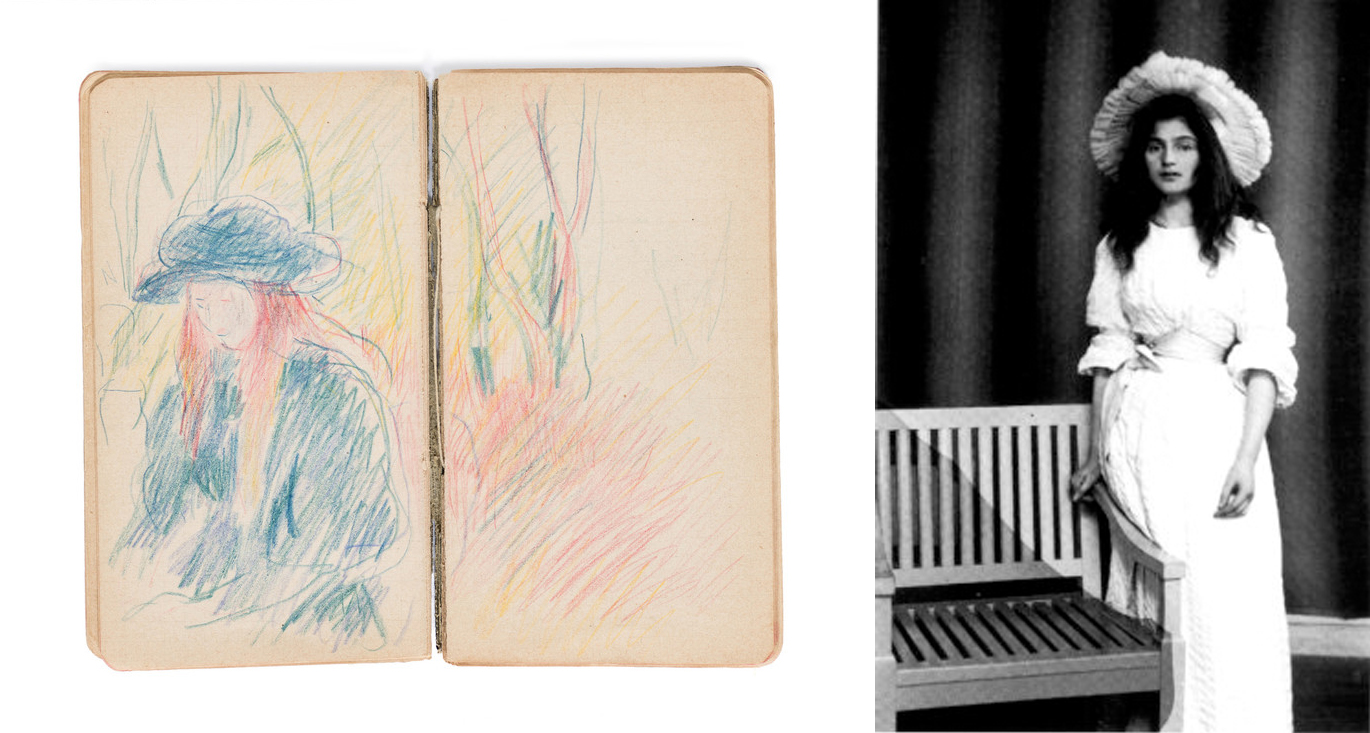

The Saar exhibition prompted me to consider sketchbooks by other artists in LACMA's collection. One in particular—a sketchbook that belonged to Berthe Morisot—has become a personal favorite because it offers a glimpse into the daily life and artistic process of this important Impressionist artist. The sketchbook dates from 1891 to 1893, when Morisot was in her early 50s, and shows clear signs of wear and use evident in the water stain and split binding.

.png)

Measuring 5 7/8 x 3 3/8 inches (about the size of your average smartphone), Morisot carried the sketchbook with her, in a purse presumably, on visits to the Bois de Boulogne, Tours (southwest of Paris in the Loire Valley) and Mézy (northwest of Paris), as annotated by her daughter on the front page. A sticker on the inside cover indicates that the sketchbook was purchased at P. Thominet, a purveyor of artists’ materials on the Avenue Victor Hugo in Paris’s 16th arrondissement. At the time Morisot lived not far away on rue Villejust in an area known as Passy near the Arc de Triomphe.

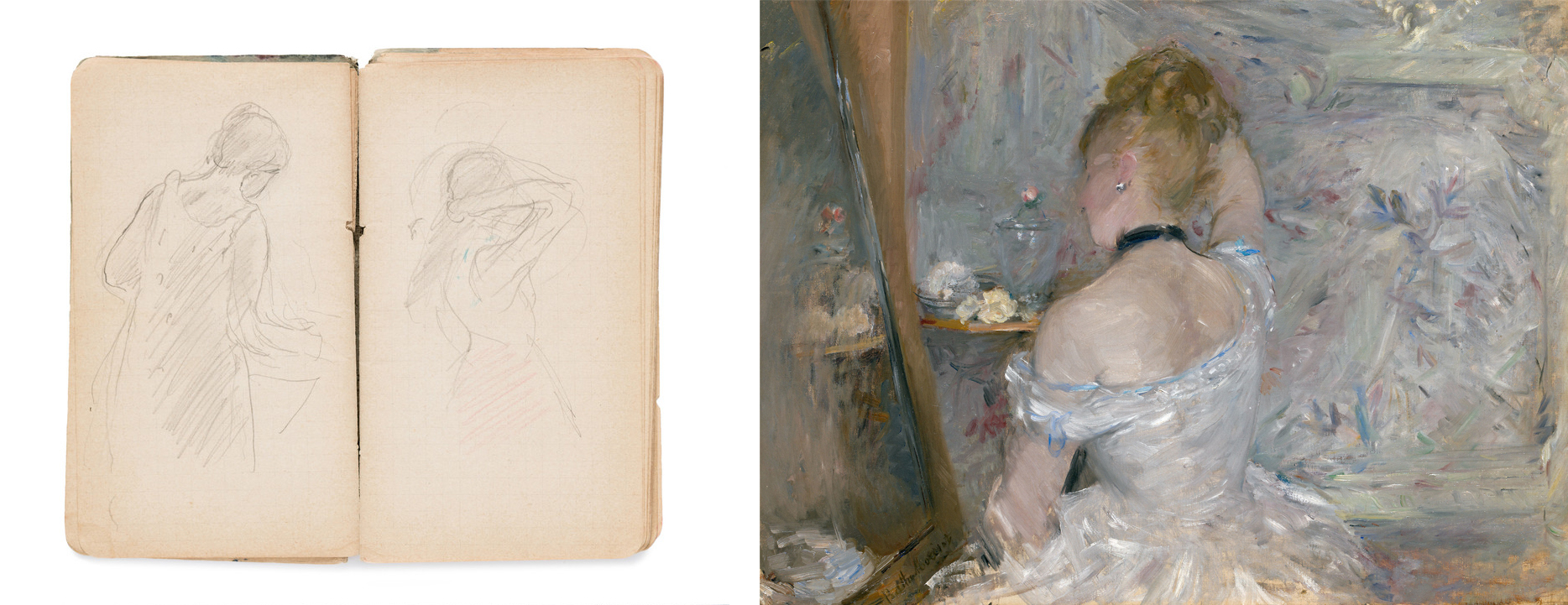

Morisot is best known for her sensitive portrayals of women from the upper Bourgeois class of Parisian society, of which she was a part, depicted in domestic settings and parks that she, her friends, and her family frequented. The scenes are sometimes intimate, like a woman at her toilette seen from behind in two quick but perceptive sketches in graphite. The image of a woman putting up, or taking down, her hair recurs in paintings throughout her career, as in this earlier work in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

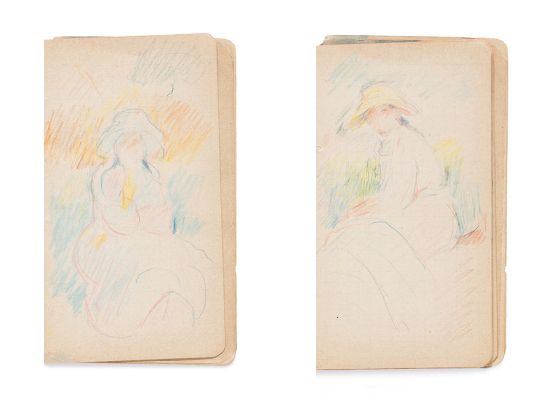

Most of the drawings in LACMA’s sketchbook are done in colored pencil which, at the time, was more of a clerk’s tool (for “checking and marking” according to a circa 1905 sales catalogue) rather than an artist’s medium, and available only in a limited palette. Attracted probably by their tidy portability, Morisot employed red, yellow, and blue colored pencils to sketch women seated, likely outdoors, given the sense of brightness captured with her characteristic light and quick touch.

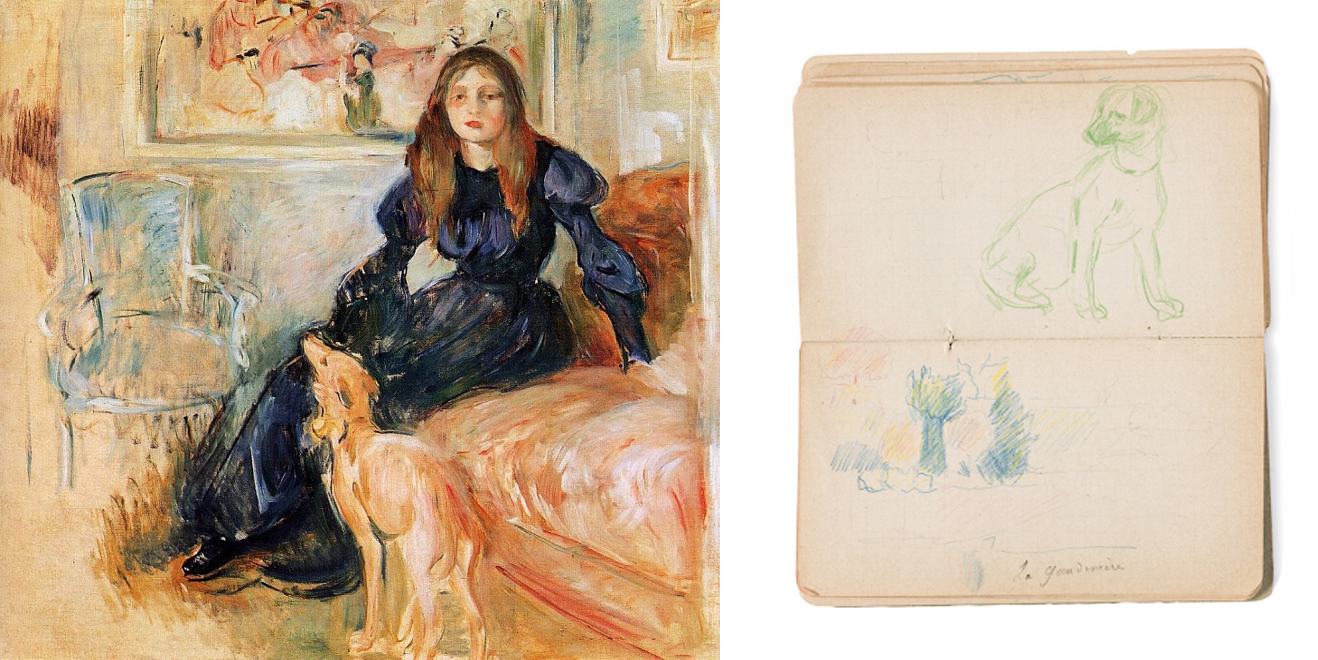

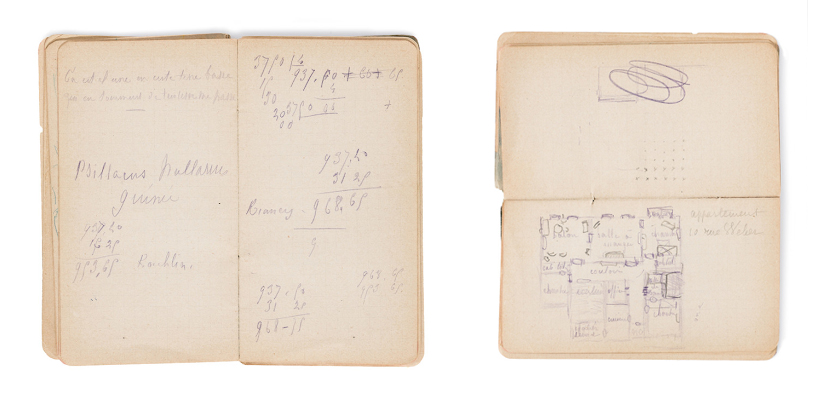

While the identities of the two previous figures remain unknown, a third sketch seems very likely to be of her daughter Julie Manet, who would have been 14 or 15 at the time and recognizable by her long auburn hair. (Morisot was married to Eugène Manet, brother of fellow Impressionist painter Edouard Manet.) An oil painting from around the same time in the collection of the Musée Marmottan depicts Julie wearing the same blue dress. The family’s pet dog drawn in green colored pencil also makes an appearance in the sketchbook, as do lists, mathematical calculations, and a floor plan—traces of Morisot’s non-artistic workaday life.

The juxtaposition of artistic exploration and banal notations that often appear in sketchbooks offers an uncensored view into the life of an artist. While seeking clues into their creative process, we also discover the artist’s humanity.

LACMA has many treasures in its vast collections. Many are feats of technical, artistic, or conceptual ingenuity. Others are more modest, like Morisot’s sketchbook, and function as casual documents of art and life that inspire differently. While a masterpiece inspires admiration, a sketchbook drawing may inspire action. There’s no time like the present to start a sketchbook practice. Following the advice of John Ruskin, “I should recommend...keeping...a small memorandum-book in the breast-pocket, with its well-cut sheathed pencil, ready for notes on passing opportunities, but never being without this.” (from The Elements of Drawing, 1857)