This three-part series of Unframed articles teases out pictorial details related to the black figure with the pearl earring in Jan Havicksz Steen’s 1668 painting Samson and Delilah. Seeking to unravel the layers of social relations and hierarchies gestured at in the 17th century Dutch painting, three questions serve as roadmaps throughout the series.

- Why is there a black figure behind one of the painting’s protagonists?

- Why is this figure wearing a pearl earring?

- Where did the pearl earrings seen by Steen originate?

Why is this figure wearing a pearl earring?

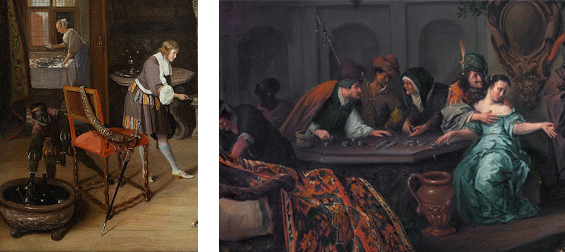

A black figure wearing an earring or earrings is a pictorial trope in Dutch and European paintings. Steen incorporated the visual detail of a black subject with a pearl earring not only in Samson and Delilah (1668), but also in other paintings like Fantasy Interior with Jan Steen and the Family of Gerrit Schouten (fig. 4) and Samson Offended by the Philistines (1675) (fig.5).

Other Dutch artists who featured this trope in their paintings include Jurriaen van Streek, Jan Mijtens, Nicolaes Berchem, and Barend van der Meer (see fig. 6 and 7). Portrayals of this imagery are apparent in other European artworks like French artist Charles-André Vanloo’s The Adoration of the Magi (c. 1760) in LACMA’s collection and English playwright William Shakespeare’s 1604 play Othello.

Black figures of all genders and Dutch white women donned pearls in 17th century Dutch paintings. Scholars note that there is not a singular meaning for pearls worn by white women in Dutch artworks. White women's social status, which is always indicated by their dress and setting, would be the key factor in how viewers read the pearls. They can also offer insight into the white woman’s sexuality, faith, class, or any combination of these three statuses.

One meaning of pearl earrings or strands of pearls on white women, as is the case with Delilah, is the subject's connection to sexual deviancy. The pearls along Delilah’s neck accentuate the plunging neckline of her dress and the pearls on her head emphasize her unkempt hair, both of which underscore her status as that of a low-class sex worker. Bartholomeus van der Helst’s portrait of Geertruida den Dubbelde (1668) and Johannes Vermeer’s The Allegory of the Catholic Faith (c. 1670–72) demonstrate how pearls serve as signifiers of either wealth or connection to God, respectively.

Geertruida (fig. 8) wears over one hundred pearls in her portrait. She pairs her pearls with an ornate ring, an embroidered gown, and meticulously detailed lace. Her dress and accessories collectively illustrate her ability to afford expensive clothing items. Scholar E. de Jongh in his 1975 article “Pearls of Virtue and Pearls of Vice” provides an in-depth analysis of how the pearls in Vermeer’s painting affirm the woman’s devotion to God. This unnamed subject, according to Jongh, represents the Catholic Church. The pearls in this painting (fig. 9), in addition to pearls in other visual and literary works, are symbols of heaven. The pearls laying on the woman’s flesh is a meditation on the Catholic Church’s close connection to heaven.

The pluralistic meanings of pearls on white women in paintings indicates that the symbol of the pearl can also hold varied meanings when black characters don them. The pictorial trope of the black person with a pearl earring across Dutch artworks may be a painterly convention to highlight the contrast between the white pearl and black flesh. The trope could also serve to highlight how the black subject, like the shining pearl, is a commodified entity. In the case of Samson and Delilah, the pearl is a visual cue of difference akin to the chain over the subject of interest's shoulder.

Both Delilah and the black individual are the only two subjects in the painting who visibly wear pearls. This connection begs questions about how the pearl genders the black character. Gender, in this instance, refers to the process of visual differentiation based on a set of societal gender codes. While Delilah’s pearls denote her sexual and class status, the black figure’s pearl reifies the precarious position of the figure in this painting. Such precarity stems from the fact that the black individual does not possess the exact attributes of either the masculine Philistinian supporting cast or the feminine Philistinian sex worker Delilah. Dress genders the black person unevenly, unlike the other characters in the painting.

Stay tuned for Part 3 of this blog series where the following question is investigated: Where did the pearl earrings seen by Steen originate?