AHAN: Studio Forum is an acquisition group of museum supporters who, over the course of a weekend, typically visit 10 artist studios pre-selected by curators in the Contemporary Art department. The group is unique in that its members then have a dialogue (forum) with the curators and offer opinions on the artistic practices and potential works for the collection. It is not a voting group but one that is based in conversation and assessment of the artists’ potential place in the context of LACMA’s encyclopedic collection.

With the pandemic affecting intimate gatherings with artists, this year’s AHAN visits were held online. Although it was unfortunate to have missed out on the immediacy of being in an artist’s studio or work space, the visits were still absorbing and thought-provoking. We are grateful to the artists who virtually opened up their studios to AHAN and thrilled to announce the works that were approved for acquisition.

We have asked this year's AHAN recipients to share the challenges they have faced this past year and what is unfolding in their lives at the moment.

Could you talk a bit about how your artistic practice has been impacted by the pandemic and the socio-political context? Have your daily ways of working changed?

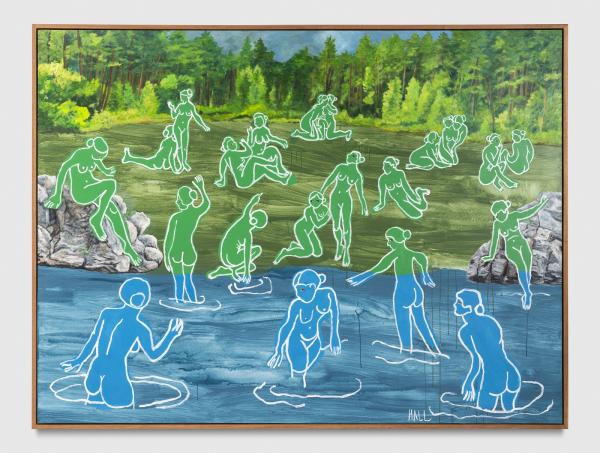

Trulee Hall: This may sound strange, but my practice has not changed much. I have stayed super busy in the past year, with two solo shows, four group shows, and writing a musical. I really enjoy being alone in the studio. Even when things totally suck, I aim to be flexible and resourceful. Thinking creatively, being inventive, and recognizing opportunities in any circumstance is an artist’s super power. I think we have all been collectively traumatized. The world has certainly felt a new level of insane and unstable. It has been a psychological challenge not to let fear and worry and anger creep in. Now that IRL art shows and openings are a thing again, I extra appreciate seeing art, my friends, and colleagues! I’m even more psyched to be part of such a vibrant art community. It all feels ripe and juicy, and more real.

Naotaka Hiro: Around March 2020, I got terribly sick with COVID-19. Even after I recovered, I suffered from persistent aftereffects for nearly a year. I always had a very close and personal relationship with my artwork physically and mentally. When I got back to the studio, I became even more conscious of my body—specifically, I started visualizing what and how my body was doing. I conversed with my body parts from head to toe, becoming even more sensitive to pains, aches, temperature, movements, sounds of breathing. Only by doing so did I feel that I could gradually overcome my fear and anxiety. This became my ritual. I struggled to produce work during quarantine—the world was falling apart and so was my body. The chaos surrounding the election, the storming of the Capitol, the human rights abuses, especially the increase in hate crimes against Asians, deeply disturbed me.

Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio: I realized many years ago that I couldn’t just make art in a studio. I make most of my work outside. A few years ago my father and I were arrested as we cleaned car exhaust off of a tree on Pico Blvd. They assumed we were graffitiing, dangerous, and someone had called the police. We had orange vests on and they had their guns out. It took me six months to work outside again, and MaSeCa was the first piece I made after this incident. It made me even more aware of the danger of being a POC in public space. The deadly toll this pandemic has had on Latinx communities here in L.A. has felt akin to the deadly toll police brutality has had on us. Whether it's across borders or across town, the act of leaving your home continues to be an act of courage. That's what inspires me to capture the marks and residues that document our existence in public. Not being able to make work in public space, I turned my garage and little back house into a ceramics studio. With shows postponed I had time to think about what I was making and focus on smaller details (for better or worse). Hopefully, the plants around the city took a deep breath.

Maya Stovall: I am interested in talking about how the pandemic has affected our thinking and cognition, if at all. So far, the pandemic took the lives of about 3.88 million people globally, 900,000 in North America, and over 600,000 in the United States. White supremacy is the socio-political context in which these disproportionate deaths continue. The COVID-19 situation is not the exception but rather the rule of moral philosophy and practical law. We can trace the genocide that the pandemic quantifies through all areas of cultural, economic, social, and political life. For instance, about 1.8 million people are imprisoned in the United States. Currently at least 8,100 children are imprisoned by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, and at least 13,600 people are imprisoned by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Fatal police shootings in the country are rising. Acts of hate against nonwhite people are increasing. What will we do about this? I am compelled to ask this and related questions in my work.

Since museums and galleries were closed for a long time during the lockdown, what other resources or sources of inspiration did you find yourself drawing from during the pandemic?

TH: I love books and lectures. The opportunity to learn from the most brilliant humans throughout history through books is incredible! I generally listen to something I find inspiring while I’m working, cleaning, walking, gardening, driving. There are many stages of the art-making process that are labor intensive and somewhat monotonous. I relish this process-oriented time as much as I love the “aha!” moments. Most generally I research topics related to my current projects, including philosophy, psychology, history, mythology, mysticism, and science. I also love looking at images—I gobble up art books and do plenty of Google images searches related to current projects. I love to listen to music actively. Choosing the right music for the right situation is important, as it greatly affects my vibe while I’m working and thinking. Nature is also a wealth of inspiration. I feel replenished by spending time listening to the wind and experiencing the beautifully choreographed, ultimately complex order/chaos that is nature. I also have a dog and two cats that have kept me company, amused me, and kept me sane—along with my amazing partner, who I learn from and enjoy everyday!

.jpg)

NH: Not being able to go to museums was one of the most difficult things for me during the pandemic. Before the lockdown, I often spent hours at museums, for example, at LACMA’s Ahmanson Building, where I sat by the permanent collections. Growing up in Nara, Japan, I lived by old Buddhist temples and shrines. Staying alone at museums can have similar effects on me. It is not just meditative, but it is a sort of reviving experience. During the pandemic, I had to dive in and seek alternate sources in myself, more personal, even deeper than before, such as memories, emotional movements, simple habits, reactions, along with the method I described above. At the same time, I tried to keep making art to keep myself up. I worked harder and longer than before. Consequently, I produced double the amount of works during this time.

ERA: I was trying to visually consume as much as I could online. I found amazing archives and information that had already been digitized and uploaded. I have also been doing research by calling people and recording their stories. When I went to a gallery show for the first time, I kept blinking, hoping to see the works with the same eyes as before. I was so used to seeing the same things every day that my eyes could not make sense of new images that had scents, texture, a profound energy. Working from home, I was constantly between artful acts in the studio and artful acts in the garden and artful acts in the kitchen. It concretized the idea that the removal of functionality from art objects has been a ploy of colonial appropriation. The historical separation of craft and high art was a tactic to steal the aesthetics and technical achievements of Brown and Black cultures without also taking the care and cultural understanding—the aesthetics of usefulness is integral to a lot of art from the non-Western world. I’ve also been deeply inspired by artists and institutions that used their resources and platforms to provide aid to our most vulnerable communities when our government was not doing enough.

MS: I grew up in the museums and galleries of Detroit. These spaces are incredibly generative and, regardless of cultural institutional flaws that flow from the overall socio-political context, these are some of the spaces where we are able to consider alternative ways of thinking and living. These spaces actually make space and I chase that feeling of space in my work. I also work through silence, isolation, and self-imposed asceticism. When I’m making a new series, I deliberately avoid looking at any work in that category as the conceptual sketch of the work is developed. Whether the medium, I turn myself away from existing works in this medium and I ride an internal wave: drinking my own sweat. I protect the space around me to let something kind of new develop. After a series or concept is solidified I then end my fast and gorge myself on the work of other artists, drinking and eating again, like we all love to do. In some ways the lockdown has been an extended fast. I am looking forward to breaking the fast.

What's next for you?

TH: I currently have two solo museum shows: at the Zabludowicz Collection in London (closing soon) and at the Villa Schöningen in Berlin (up until September). I’m also currently in three group shows: at Ochi Projects and Various Small Fires in Los Angeles as well as at the Contemporary Art Digest in Hong Kong. Another upcoming show is at domicile (n.) gallery in Los Angeles. I’ve also been doing a ton of college lectures and grad student visits. And in general I’m making a ton of new work. I’m psyched to get back to planning larger video shoots and collaborating with my talented friends!

NH: My solo exhibition just opened at The Box in Los Angeles (until July 24). All the works in the exhibition were done between 2020 and 2021 during the pandemic. Currently, I am writing several scripts for films that I want to make, one of them about an early period of the Gutai Art Association, a Japanese art collective active from 1954 to 1972.

ERA: Pansa Del Publico is a public sculpture I recently installed at the LA State Historic Park. It comprises many of the realizations I had during the pandemic. It references the Ceiba tree, but it’s also a functional wood-fired oven. I always thought Serra and Judd sculptures would make great ovens and planchas. Is the hollowness of a lot of public sculpture wasted space? Cooking and feeding people is an artful act and the sculpture demands it. The ceramic thorns that adorn and protect the piece were made in the same way that the bread is made inside. We hold the knowledge of our ancestors in our hands and we learn to be artists by watching our families cook and clean and play. Now that spaces are opening up I am glad we can see art again in person. I hope to gain access to archives around the city and make work in public space.

MS: This fall Parrisch Heijnen in Los Angeles presents a solo exhibition, and I am an artist-in-residence at a university in the southwest for the duration of the academic year. I continue teaching where I’m an assistant professor in the Liberal Studies department at California State Polytechnic University (Cal Poly), Pomona, and continue to tour for my new publication, Liquor Store Theatre. My work will be at Art Basel Miami to close the year.