This Sunday, June 19, is Juneteenth. The United States’ youngest federal holiday was only made official last year, but has long been celebrated by Black American communities to commemorate the country’s second independence day. The Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863, and in its wake, Union soldiers both Black and white traveled to plantations and cities across the south spreading the news of freedom to Confederate states, reading from small copies of the Proclamation. Not everyone in the Confederate territory, however, would immediately be free. Emancipation did not reach all regions of the country until two years later, when federal troops set foot in Galveston, Texas, and announced that the state’s 250,000 enslaved Black people were free by executive order, on June 19, 1865. Celebrations broke out across the state, and that day would become known as “Juneteenth.”

Over 150 years later, Juneteenth stands as a celebration of the hard-won victories of Black Americans, commemorating not just Emancipation but Reconstruction, the Civil Rights era, and today. Juneteenth celebrations honor both the history of Black Americans and their present, uplifting art, culture, and political struggles.

Continuing in the spirit of Black American Portraits—the exhibition presented earlier this year that chronicled the ways Black Americans have envision themselves, centering love, abundance, family, and community—we are proud to continue to celebrate the voices of Black artists with artwork in our collection. LACMA’s exhibition Family Album, on view at Charles White Elementary School, explores how photography, especially family snapshots, has presented an opportunity for Black Americans to take control of their own image. What Would You Say? Activist Graphics from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, at the Riverside Art Museum, explores the creative ways artists and activists of color have employed graphics to advocate for civil rights, oppose unjust policy, and press for change. In our Modern Art Galleries, significant works by Black artists prove that although people of color have often been overlooked in the canon of art history, and in the history of the United States, they have always remained a crucial part of it. On this holiday, we encourage reflection on the meaning of Juneteenth and on the critical fights for racial justice in America’s history and its present.

Below are just a few artworks currently on view, as well as some recent additions to LACMA’s collection, memorializing African American history and celebrating Black joy and liberation.

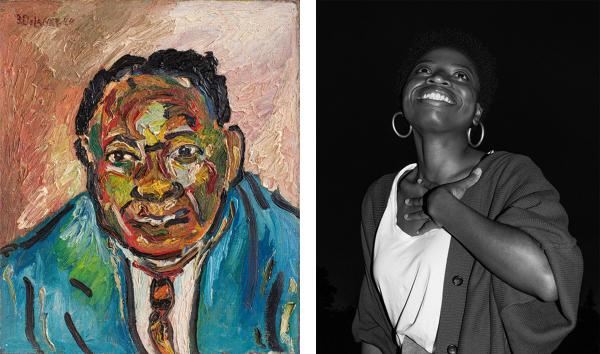

![Beauford Delaney, Negro Man [Claude McKay], 1944, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of the 2022 Collectors Committee with additional funds provided by the Robert H. Halff Endowment, the Modern and Contemporary Art Council, and The Buddy Taub Foundation, Jill and Dennis Roach, Directors © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY](https://unframed.lacma.org/sites/default/files/attachments/436964scr_6ade1f0ca06ad9f%20%281%29.jpg)

Beauford Delaney

Negro Man [Claude McKay], 1944

Born in Tennessee, Beauford Delaney settled in New York, where he took part in the vibrant Harlem Renaissance and Greenwich Village art scenes. In the early 1940s he began a series of portraits, employing bold colors and gestural paint application to depict family, friends, and mentors; among the influential cultural figures who sat for him were James Baldwin, W. E. B. Du Bois, Duke Ellington, Henry Miller, and Edna Porter. In this work Delaney portrays his friend, Jamaican American writer and poet Claude McKay, a key Harlem Renaissance figure who wrote about Black life, racial injustices, and socialist revolution.

Read more about this recent acquisition.

John Biggers

Sharecropper, 1945

John Biggers is known for making social realist paintings depicting Black life in the American South. Here, the artist focuses on sharecropping, a farming system that emerged after the Civil War and lasted until the 1940s. Under the system, formerly enslaved African Americans and their descendants worked fields belonging to primarily white landowners, preventing them from acquiring capital and land of their own. The solitary sharecropper in Biggers’s work conveys both exhaustion and strength: his face is lined and his hands are gnarled, but his posture is upright and he appears almost saint-like, with closed eyes and white hair framing his head like a halo.

Read more about the artist who created this recently acquired work.

Betye Saar

Mojo Bag #1 Hand, 1970

Betye Saar’s Mojo Bag #1 Hand is among the pioneering Black artist’s earliest assemblage works based on non-Eurocentric sources. The cowhide bag is informed by Native American leather pouches, typically sewn by women, which would include small inner pockets guarding an amulet or talisman (here referred to using the African American term “mojo”); the hidden interior pouch of Saar’s assemblage holds a bone. The hand of the title refers to the hamsa, a palm-shaped amulet popular throughout the Middle East and North Africa considered a defense against the evil eye. Saar often includes the silhouette of her own hand in her work as a symbol of fate or fortune.

Now on view in the Modern Art Galleries.

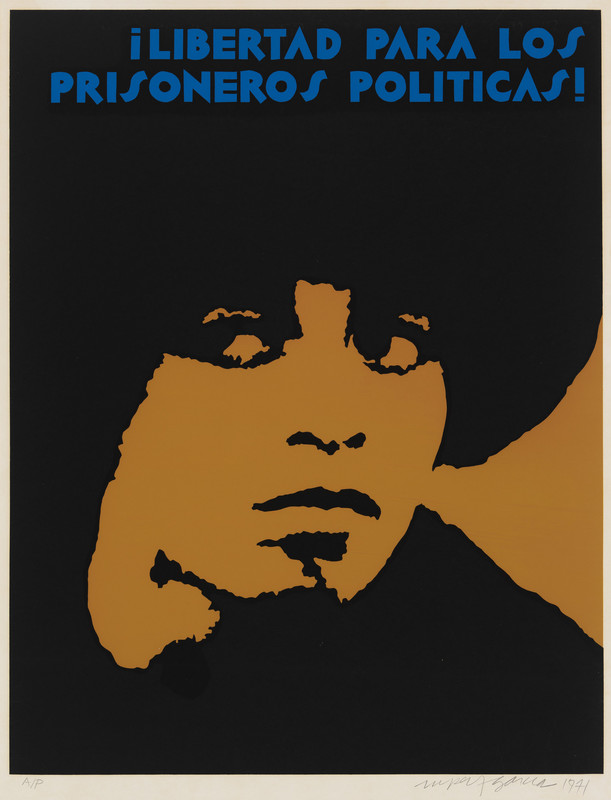

Rupert García

Libertad para los Prisoneros Políticas!, 1971

Rupert García’s work was deeply influenced by political art of his era, including the Black Panther newsletters of Emory Douglas, photographs of his mentor John Guttman, performances of El Teatro Campesino, and Cuban posters. This poster portrays civil rights activist and professor Angela Davis, who inspired an international movement calling for her freedom following her arrest on murder charges in 1970. Musicians including John Lennon and Yoko Ono and the Rolling Stones wrote songs to draw attention to her imprisonment, and her face became ubiquitous on buttons and posters. As a testament to the power of García’s depiction of Davis, the image was reproduced for further distribution by the leftist Peace Press in Los Angeles. Davis was acquitted of all charges in 1972.

Now on view in What Would You Say?: Activist Graphics from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Zora J Murff

American Mother, 2019

Zora J Murff is an artist and educator living in Arkansas. Murff uses photography to explore the role that images play in shaping collective belief systems. American Mother derives from the series “American Mother, American Father,” which Murff made in Arkansas and Mississippi while visiting his familial birth places. Murff explained “visiting the birthplaces of my maternal and paternal families forced me to reflect on how we build identity, how identity can be created for us, and how those phenomena collide.”

Now on view in Family Album: Dannielle Bowman, Janna Ireland and Contemporary Works from LACMA.

Micaiah Carter

Family, 2020

Micaiah Carter created Family in the neighborhood in South Los Angeles where his mother lived in her early adult life. The artist worked with models to represent his own family members, with a version of himself as a boy pictured at the center. Carter studied photography at Parsons School of Design and has made a growing oeuvre of Black celebrities and youth, inspired by the ideals of the “Black is Beautiful” movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Carter's father, Andrew Carter, a retired Air Force Sergeant, matured during the age of Black Power. Carter pored through his father’s scrapbooks, which led him to discover the work of John H. White. The Chicago photojournalists’ ability to capture his subjects with dignity, regardless of their social station, left an impression on Carter’s image making. “I’m using the past as a compass,” Carter has said, “while at the same time shooting new trajectories.”

Now on view in Family Album: Dannielle Bowman, Janna Ireland and Contemporary Works from LACMA.