Taking as a base any one of my programmations, we are now able to recreate the work and a countless number of other compositions the machine proposes. In this way, the limitations due to the artist’s method of working in a studio would be overcome.

—from Victor Vasarely’s proposal to LACMA’s Art & Technology Program (1967–71)

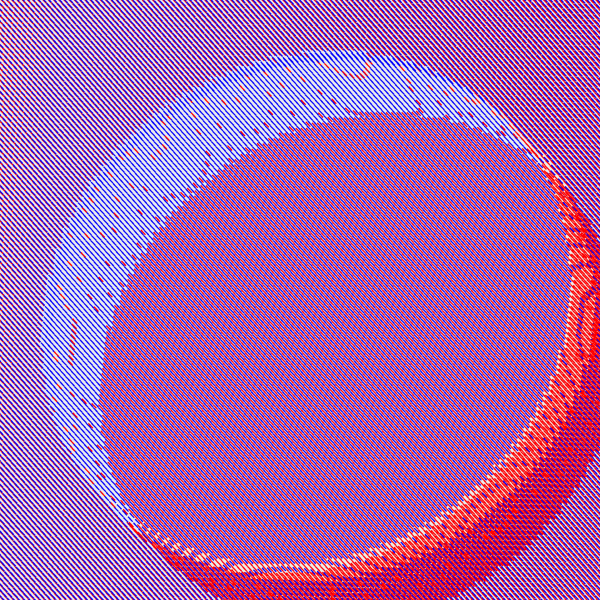

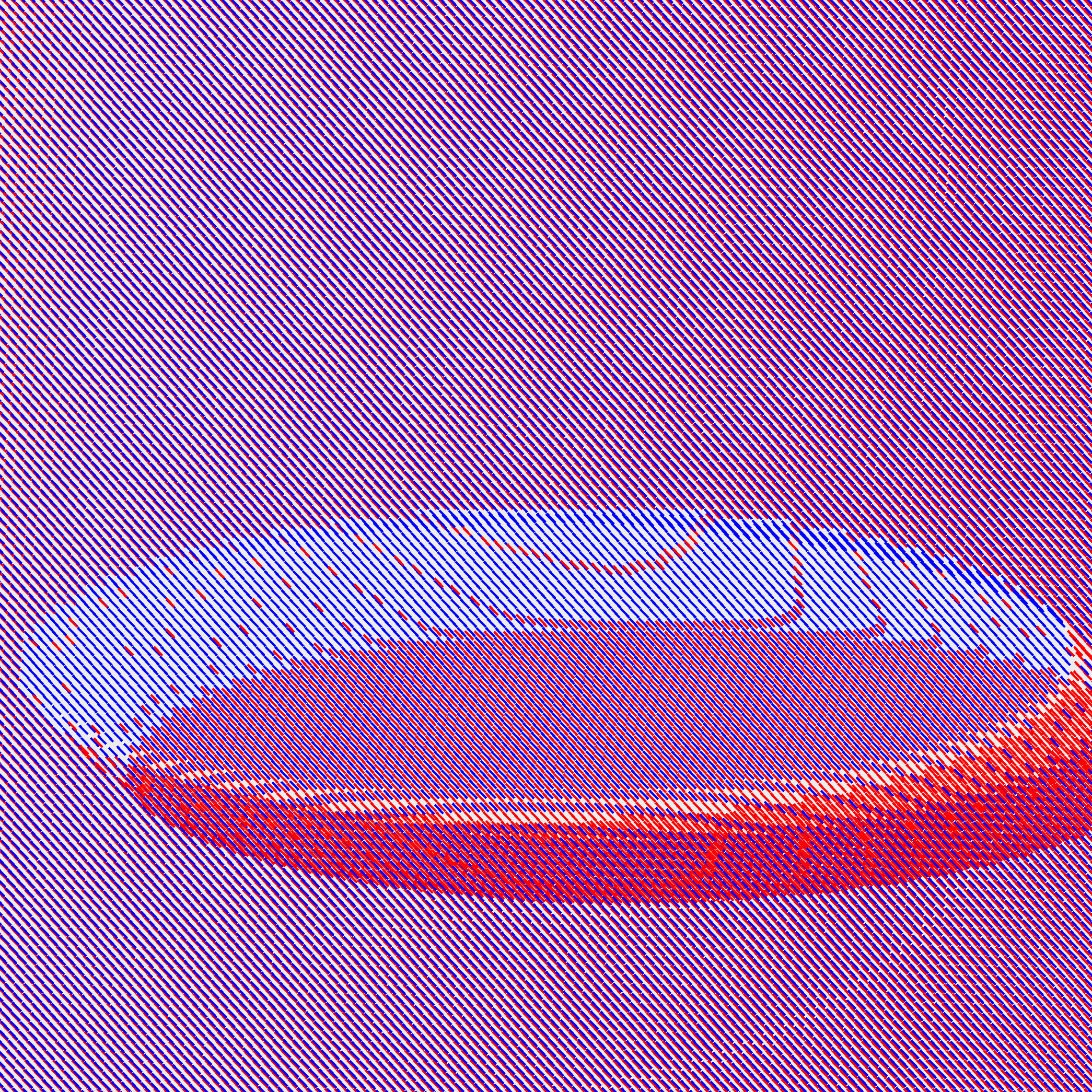

In conjunction with Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab presents Casey Reas: METAVASARELY and An Empty Room. The project is a simulation and homage to Victor Vasarely’s unrealized proposal for LACMA’s original Art & Technology Program (1967–71), which defined a machine composed of lights arranged in a grid that would generate millions of different visual patterns related to his paintings. The proposal reflected the artist’s interest in cybernetics and permutation and, thanks to Reas, is enjoying a second life in our digital age. We sat down with Reas to learn more.

In the late 1960s, IBM estimated that it would cost $2 million to create the machine Vasarely envisioned. What was it like to evolve the concept and manifest it in a digital space?

My first instinct was to build the machine. The electronics needed to produce Vasarely’s machine have advanced so much since then. But, thinking more, the idea of simulating it in software felt more flexible and exciting. I’m glad that I made this decision because I think the machine Vasarely imagined at that time was far less interesting than what he was doing with more traditional materials. In his painting practice he developed his diverse “plastic alphabet” of forms and colors that he combined in endless variations. When he created a painting with this alphabet, the way he combined the forms was complex. In contrast, the machine specified in the Art & Technology proposal is limited to only circles of light; it didn’t have the same flexibility. In re-imagining the machine in software now, I can explore his full visual palette while still keeping to the core idea of Vasarely's Art & Technology machine proposal.

In the 1960s, Vasarely was working on this Planetary Folklore and Permutations and Algorithms series of works. Like the proposal he created for LACMA, these artworks included a regular square grid. (His iconic artworks that warp the grid came later.) In each grid element, he would place one or more shapes (e.g. a circle or square) and each shape would have a different color from a custom palette defined for each artwork. I spent months attempting to create a software system that could produce a wide range of images that felt like they might have been produced by Vasarely. I was able to sketch out “the big picture” but looking at his work with even more detail, nearly all the artworks contain exceptions to the rules he defines within them. Although they appear so rational and structured, they have idiosyncratic details that are completely essential. So, I switched directions and created what you see now. I found it was far more interesting to make an instrument that allowed me to perform, rather than automate, Vasarely’s idea.

In general, I think it’s a logical transition to think about Vasarely’s paintings as software. As he wrote in his Art & Technology proposal: “In fact, as of this period all my works are programmated; colors, tones and form all being reduced to a simple code.” He was walking the walk, it was more than an idea. He reduced his color and form palettes and assigned a number to each. He arranged numbers into grids as ways of making patterns before seeing them as images. His mind was in the space of coding—before the technology of digital computers could meet his needs.

You’ve been working with software for over 20 years and are a pioneer of digital art. What forms do you think your work would take if you were making art before the arrival of the personal computer?

I’ve been asking myself this question for a long time. My life as an artist really started with writing software. I had ideas about things that I wanted to make that I couldn’t make any other way, so I learned to write code to create my earliest artworks. The ideas that are closest to me (simulation, emergence, systems) require software—my work and ideas are bound to what computers can do. At the same time, the work that I make wouldn’t exist without the traditions of drawing, painting, film, video, and performance from the last centuries. I’ve spent countless hours in museums looking at paintings and watching films. With my work, I draw from the histories of abstraction in painting and drawing as well as in avant-garde film and experimental video.

As we see in Coded, this history of artists working with software and digital computers goes back over 60 years. In the first decade, there were some amazing experiments in film, but the majority of the work used computers to create drawings, specifically drawings that were rendered by physical machines. This was the era before most computers had screens and before digital printers. Artists would see their images for the very first time as they were being slowly rendered by huge machines. In contrast, working with computers now, we see what we’re making immediately—we have constant feedback.

I’ve made works on paper created through code since the beginning of my career and I’ve also experimented with plotter drawings, but the essence of my work requires changes in time. I think of myself as an expanded experimental animator who writes software rather than working with film for video. If I was born earlier, I like to imagine I would have found my way into experimental film, like Stan Brakhage and Paul Sharits.

In addition to Victor Vasarely, you’ve recently been developing similar tributes to artists including Vera Molnár and Jesús Rafael Soto. Can you share some background on these projects and why you focused on these artists?

The last few years, I’ve focused on a series of work titled CENTURY. This work started in 2012, but it’s been a stronger focus lately. This work takes two forms: artworks that I create that relate specifically to painting and drawing in the 20th century in some way, and visual research that informs the first category. For LACMA, I’m creating one of each. METAVASARELY is an homage to the work of Victor Vasarely from the 1960s and An Empty Room extrapolates what I learned from METAVASARELY into my own ideas and visual language. I’ve focused on Vasarely, Molnar, and Soto through commissions. Outside of those commissions, I’ve created work in relation to Kazimir Malevich, Brigette Riley, François Morellet, Ellsworth Kelly, Herbert Franke, and Agnes Martin. The idea is that “generative art” has its foundation outside of computers, and many painters in the 20th century were working in a way that’s very similar to artists working with code now.

My Hommage á Molnar just opened last week in the Machine Imaginaire exhibition at DAM Projects in Berlin. This show celebrates Molnar’s 99th birthday and it includes drawings and paintings as well as early computer drawings. My contribution is a software instrument that I imagined Molnar could have used in the 1960s to explore the precise visual language she was working with at the time. I used the extensive collection of Molnar’s work in the Spalter Digital collection to do the research and my instrument allows anyone to move through her iconic visual language from the time to discover new possible drawings.

METASOTO was a commission from Tina Ryan, curator at the Albright Knox Museum, for her Peer to Peer exhibition hosted on Feral File. Twelve other artists and I were invited to select an artwork from the museum’s collection to create a new work in dialogue with it. I’ve been an admirer of Jesus Rafael Soto’s work since I first saw it and this was an opportunity to dig deep into his artwork Bois-tiges de fer (1964). I created 64 new software works, each a response to Bois-tiges de fer.

METAVASARELY and An Empty Room feature online and in-gallery components, beginning with METAVASARELY on lacma.org.

The Art + Technology Lab is presented by

The Art + Technology Lab is made possible by Snap Inc.

Additional support is provided by SpaceX.

The Lab is part of The Hyundai Project: Art + Technology at LACMA, a joint initiative exploring the convergence of art and technology.

Seed funding for the development of the Art + Technology Lab was provided by the Los Angeles County Quality and Productivity Commission through the Productivity Investment Fund and LACMA Trustee David Bohnett.