Cactoid Labs curator and co-founder Lady Cactoid recently sat down with artist Emily Xie to explore her process, the stories behind the art she currently has on view at the museum’s Stark Bar screens, and the work she is creating in dialogue with LACMA’s permanent collection for the project Remembrance of Things Future, curated and engineered by the experimental blockchain consultancy Cactoid Labs.

Building upon LACMA’s historic engagements with Art and Technology, Remembrance of Things Future is an invitation to travel via the blockchain back in time through the museum’s encyclopedic collection. Utilizing tools such as generative code Emily Xie, alongside other pioneering artists, has been invited to select objects from LACMA and make new digital art inspired by the museum’s holdings. Released on the blockchain in phases, a percentage of proceeds from these limited Remembrance of Things Future digital editions goes to support LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab. More information on this project can be found at lacma.cactoidlabs.io.

Hi, Emily! Maybe you can share with us a bit about your background and how that led you into generative art.

I’ve been making art and tinkering with computers my entire life. Growing up, I experimented quite a bit with traditional art methods: everything from charcoal to oil pastel to watercolor to screen printing. Later on, I started dipping my toes into newer forms of media like digital drawing and photography. All the while, my younger self had spent considerable hours on the computer: gaming, building websites, and exploring the vast expanses of the internet. In terms of my formal education, I had studied at Harvard, where I earned a bachelor’s of history of art and architecture, and a master’s of computational science and engineering.

I initially began my career as a software engineer. It was during the earlier phases of my work life (around 2015) that I’d first discovered generative art—a passion that I’d pursued continually on the side while working. Now, as a full-time generative artist, I consider myself lucky given that art and computing have consistently stood as my foremost interests. Being able to combine both fields into a single practice feels like a privilege.

Can you speak about your process? As a generative artist, you make art with code. What does that look like?

I bring together my experiences such that my visuals navigate between many dynamics in a collage-like manner. My work tends to be both organic yet systematic, and also evokes different textures, materials, and aspects across various mediums.

When I set out on a new project, I typically begin by aggregating images across genres, time, and media as a subconscious way for me to uncover what’s currently inspiring me.

Once I have some ideas in mind, I begin to experiment with generative systems that might move me towards that direction. I make my art with code, using Javascript and p5.js as my primary toolset. So, this typically means I’m either creating an algorithm from scratch, augmenting an underlying procedure that I’ve already written, or exploring known techniques in the field while combining them or bringing my own spin to them. At this point in the process, things are the most in flux—I don’t necessarily have a firm idea of the end result, and so I spend significant time tinkering and playing at this stage.

After getting an underlying system in place, I try to rapidly prototype with it. Since my final pieces tend to be entirely code-based, it’s important to me to be able to roughly visualize my ideas using some sort of digital drawing or image editing software. This is a particularly great way to get a sense of what a given texture combination or composition of elements would look like. Otherwise, one might spend an entire day programming a theoretically interesting concept, only for the end result of the algorithm to completely miss expectations. Once my algorithms move closer to completion, I then begin experimenting by simply adjusting the code itself. Of course, my process varies based on the particular project, but overall, this is typically how I work.

Were you aware of computational art during your studies? Did you know other computational artists before you began?

In my studies, I wasn’t aware of computer art in the purest sense, but I had certainly studied and found myself drawn to artwork that incorporated computational or algorithmic methods. For instance, I had studied Donald Judd’s minimalist methods and his usage of repeated simple shapes and objects in order to create systematized works. I was also fascinated by Sol LeWitt’s instructive drawings and their underlying algorithmic qualities.

When I started playing around with generative art, I was aware of the handful of practicing generative artists and educators at the time: for example, Lauren McCarthy, Tyler Hobbs, Zach Lieberman, Kyle MacDonald, and Daniel Shiffman. I found these folks deeply inspirational as they showed me all the possibilities of what one could create with code as a creative medium.

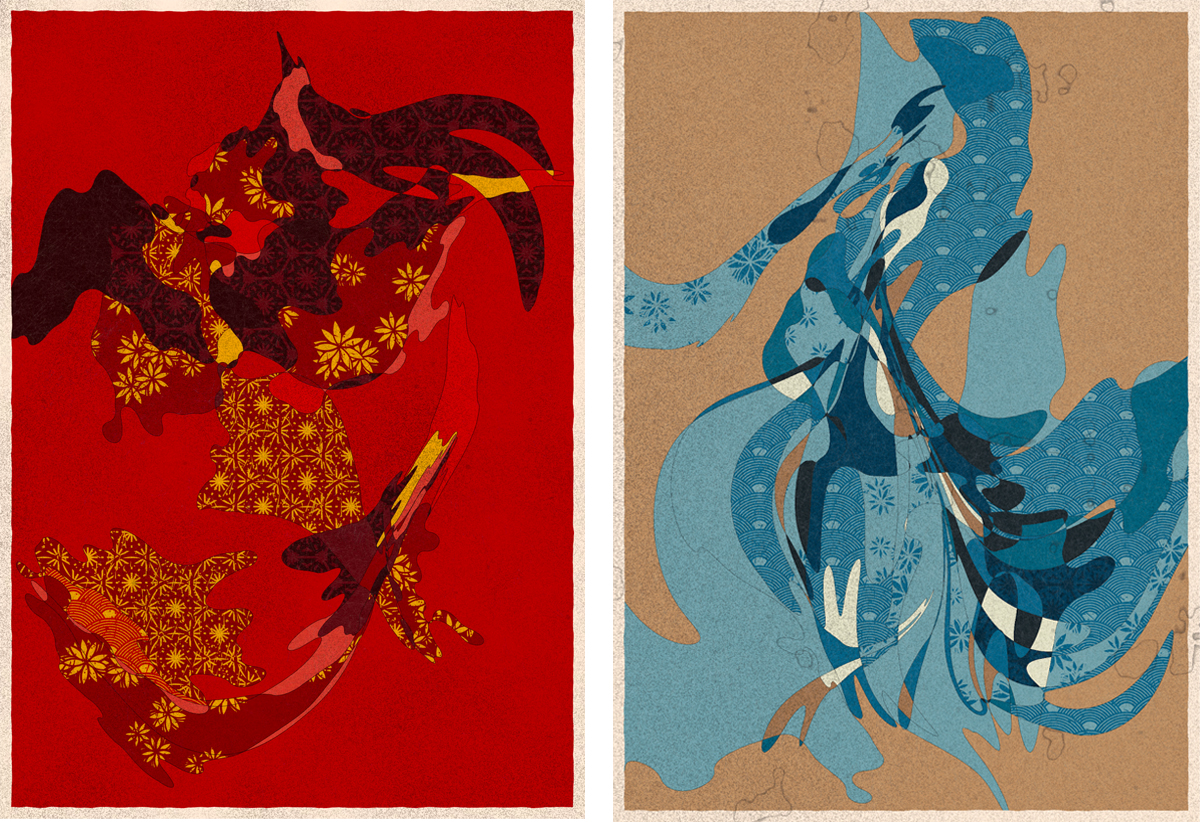

Can you briefly describe the story behind your two recent series, Off Script, which we are currently exhibiting on LACMA’s outdoor Stark Bar screens, and Memories of Qilin? What were you trying to accomplish in these collections?

With Memories of Qilin, I was inspired by East Asian art from an aesthetic standpoint.

I’d always been fascinated by how Ukiyo-e woodblock prints combined so many colors and patterns in a way that felt cohesive and beautiful. At the same time, I also wanted to channel that impression of movement that one would find in Chinese brush paintings. From a more conceptual perspective, I was interested in exploring the concept of folklore. Early on, I realized that my algorithm gave rise to shapes and figures that were almost representational. When I noticed this, I decided to explore this further, and spent significant time tuning the parameters to maximize this effect. I wanted people to look at the outputs and connect with them on a personal level by bringing their own interpretations—in the same way that one connects with stories and folklore.

Off Script was my next series after Memories of Qilin. Through this work, I continued to examine some of the most fundamental aspects of aesthetics that mattered to me. I turned to the concept of abstract art, as I wanted to explore composition, shape, form, color, and texture in a distilled manner. Off Script brought the concept of medium to the fore, as I tried my best to replicate paper. Much of early 20th-century collage created a dialogue around material in its raw form, so I thought it’d be interesting to create something as material as paper in an art form as immaterial as code.

Can you speak about what works in LACMA’s permanent collection inspired your generative series Interwoven for Remembrance of Things Future? What drew you to the works?

As someone fascinated by texture and materiality, I was naturally drawn to quilts. There’s something compelling about fabric; it’s deeply sensorial. There’s a sense of temperature: quilts cover you and provide you warmth as you sleep. It also evokes the sense of smell; when looking at these images, I imagined the scent of an old blanket locked away in storage.

At the same time, quilts are composed of disparate fabrics. I love what that means: each piece in a quilt brings its own history and story. I’m fascinated by how different patterns can come together to create a cohesive and compelling whole. This is probably something that you can see in my general body of work. It’s something I find myself eternally captivated by, and of course, continue to investigate in this upcoming release.

Another thing that fascinates me about quiltwork is the gendered lens through which one may interpret the artform. Women throughout history have used quilts to tell their stories, and even immortalize them as they passed down through generations. In the past, quilting was one of few avenues for women to express themselves with. I thought it’d be interesting to be inspired by and to explore elements of quiltwork in the realm of generative artwork, especially as the creative coding field has historically been male-dominated despite the role that women have played in shaping it.

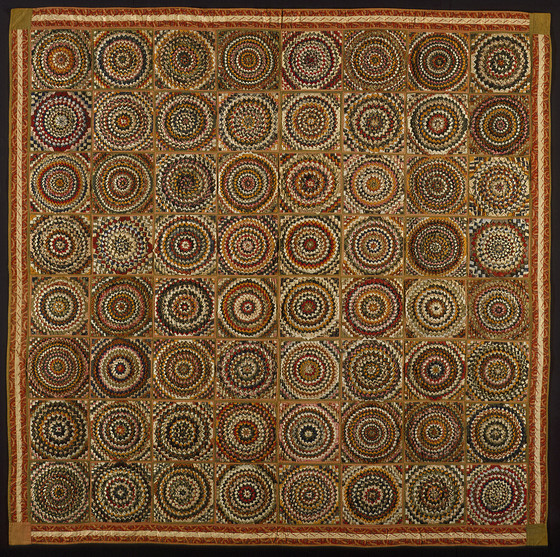

And finally, I was drawn to quiltwork because I felt that it embodies so much of what generative art is all about. There’s a tension between the computational and the human that’s inherent in the craft. One particular piece I looked at in depth was Martha Lou Jones’ “Bullseye” quilt from 1896, where that dichotomy is beautifully evident. The general structure is rigid and geometric as it is composed of a grid of repeating circles. Yet, at the same time, if you look closely, you’ll notice that each of the bullseye is imperfect, and the colors of each ring appear selected at random. This tension is something that I definitely aimed to highlight and explore in my series.

This relationship between quilts and computational logic is fascinating. It makes me think about one of the earliest computer programmers, Ada Lovelace, who in 1843 wrote the algorithm for a mechanical computer system called the Analytical Engine. Lovelace’s algorithm was inspired by the punch card method used in new Jacquard textile looms of the day. I totally see that shared foundational language between textiles and computing in your work. Building off your fascination with textiles and color, you have such an elegant sense of balance in terms of positive and negative space. How do we see your formal process come through in the different parameters you recently created in p5js in response to quilts in LACMA’s collection?

Balancing control and randomness is pretty integral to my process, especially when creating a longform series. I’d say that for this project—Generative Patchwork and Bullseye—this interplay shows in the way that the underlying compositions are generated.

Here, I programmed a system that wields the randomness introduced by the machine to create infinitely varied forms. The resulting shapes—filled with quilting patterns—are meant to feel unexpected and surprising, oftentimes even appearing creature-like. I wanted the forms to be interpretable in order to nod to the narrative aspect that's become so integral to the tradition of quilting. I wanted each output to have its own interpretable story; I wanted people to look at the forms that emerged and to imbue them with their own personal meaning.

At the same time, the notion of constraint came in terms of compositional harmony. I used a set of heuristics to ensure that each shape adequately occupied enough canvas space, and were nicely counterbalanced by the bullseyes. I also spent endless hours fine-tuning the spacing and sizes of the elements. Deciding these parameters was a mostly intuitive process; I continually adjusted the ranges and visualized the results until the outputs looked right to me.

While the shapes and composition maintain a pretty strong duality between chance and constraint, I apply a significantly more controlled approach in creating the color palettes. Color is important to me—I believe it holds particular power in creating emotional and symbolic association. As such, the palettes and color choices for each quilt pattern are manually selected. I pretty obsessively fine-tune these combinations, setting different distributions and iteratively testing until it feels right.

In some sense, my code and its parameters create a digital loom, setting up foundational configurations and instructions. Yet, at the same time, there’s a level of variance and uniqueness, and a certain human touch—much like the process of quilting itself.

What is the relationship between your earlier edition Generative Patchwork and Bullseye and this new longform series, Interwoven?

Whereas Generative Patchwork and Bullseye from Volume 1 is a single curated output, Interwoven is the generative on-chain exploration of the algorithm’s potential. Beyond that, Interwoven investigates quilting further, roping in more pronounced patterns to enrich its patchwork appearance. I also overhauled the algorithm so that it would more readily give rise to forms and creature-like figures.

Juxtaposed, the two volumes form a dialogue around a fundamental concept within generative art: an artist’s highly controlled artistic vision versus surrendering agency to randomness and the machine. These are questions that early pioneers of generative art explored, like Vera Molnár or John Cage. They both approached the notion of indeterminacy in different ways; for example, with Cage completely relinquishing autonomy in his 4 ’33 piece, and Molnár experimenting with only slight randomness in 25 Squares. It’s amazing to be able to present two different ends of this dichotomy through the same underlying system in Remembrance of Things Future.