In archival work, a “dark archive” is described as a collection that is rarely or never accessed, kept and maintained but seldom seen or experienced. This can be done for legal reasons, to obey the wishes of the donor, for administrative purposes (say, for a collection that needs to be selective with how it directs its resources), to protect the materials from misuse, or to ensure that it is only seen by a privileged few. But what life are these resources being deprived of when they do not see the light? How do they continue to gather meaning if they are not experienced and their stories are not actively told and revisited?

“Mai ka pouli” translates from Hawaiian to “out of darkness,” and was chosen as the title for a unique collaborative exhibition between the Donkey Mill Art Center in Kailua-Kona, Hawai’i, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Mai Ka Pouli: (Re)presentations of Moananuiākea “explores identity and representation of Kanaka Ōiwi [Native Hawaiians] and people of the Pacific through contemporary artworks activating stories of people, places and cultures which have been historically and contemporaneously misrepresented and erased. By re-centering voices and perspectives, artists reclaim the narrative.” The source material for this exhibition is a large collection of photography from LACMA’s collection that represents the people and landscapes of the Pacific Islands, from the mid-19th century to the present, largely representing Hawai’i and the transition from the Kingdom of Hawai’i through the illegal overthrow and occupation by the U.S. Government in 1893 and into the 20th century. Donkey Mill Curator Mina Elison, who envisioned this exhibition, invited a group of 11 artists from Hawaiʻi and the Pacific Islands to help us begin to reinvigorate the stories in this collection through their art, their practice, and their personal histories.

The primary intent of this collaboration is to look into the legacy of these rich yet fraught collections and at photography as a tool and a practice. “Layered with foreign influences of colonialism, history in the Pacific continues to shape contemporary life, notably those of Kanaka 'Ōiwi and Pacific Islanders whose lands, cultural practices and values have been manipulated and exploited. Artworks reclaiming and reframing people, landscapes and events of Hawai'i and the Pacific encourages viewers to consider alternative perspectives and ways of understanding and connecting with the past, and also consider the empowering and healing possibilities of affirming one’s own identity.”

This photography collection was assembled over many decades by Mark and Carolyn Blackburn and entered LACMA’s collection in 2015, and in 2018 LACMA embarked on an Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) grant project aimed at providing greater access to the collection through registration and collections care, digitization, and research, though a major realization when I was asked to take over this project in 2018 was that we were missing a major project component—direct engagement with the communities affected by these colonialist legacies and whose ancestors were represented in these images. There was so much to unpack, literally and figuratively, with how to faithfully steward this collection and examine what stories were being told (and by whom). During an exhibition panel discussion in early April, Dr. Tarisi Vunidilo, Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo and who has worked closed with communities in Fiji to process and activate traditional and ancestral objects, talked about the chasm typically found between the museum collection spaces that hold these belongings and the communities from where they originate. As collection stewards we can often inadvertently continue to inflict the same harm over and over again when we mishandle and misrepresent the cultural materials that we strive to protect. At the same time, we have a responsibility to steward these materials through the resources that we have access to, and not shirk responsibility and pass off labor to these communities who may not have as much leverage to preserve such collections. How can we find a balance between ceding power without ceding responsibility?

The exhibition at the Donkey Mill was extremely meaningful, not just for finding a space for the collection to be witnessed and enriched by the originating communities, but to reinvigorate the stories and humanity found within it—and from within it. The stories in these images are personal, and in many cases some of the first opportunities that Kanaka ‘Ōiwi have had to bear witness to their kūpuna (ancestors or elders). The panel that took place on April 1 invited speakers such as Annemarie Paikai, Hawaiʻi Pacific Resource Librarian at Leeward Community College, who shared the work that she has done to find ways of reappropriating images from the past to give Hawaiians new opportunities to connect with their past and their loved ones whom they never got to meet or even see depicted. This is, of course, despite the sordid reasons why some of these images exist in the first place, a result of colonialist influence with the intent to “document” the Indigenous people of the places that were being colonized. Nonetheless, there is an opportunity to recenter the stories of the people in the images and restore the dignity that they deserve through this act of reappropriation. Stories such as this were core to many of the artists who created work for the show in response to images in the collection, like Saumolia Puapuaga, whose beautiful portrait of his parents evokes the intimate and dignified portraiture of Samoan royalty found in the collection. Of course, the images and the data (or lack thereof) that accompanied them also exhumed trauma of what has been erased over time. As was beautifully expressed by artist Meleanna Aluli Meyer during the opening reception, these “unknown” places and faces (a term popularly used on object labels for under-researched collections) are not unknown to the people who have called this place home for decades and centuries.

After building relationships with cultural stewardship leaders and community members in these Pacific Island communities through an advisory board process, we continue to connect with even more individuals and talk about the ways that the images in this collection could potentially find new spaces to flourish and take on new meaning (or to reconnect with their original meaning). While the images certainly hold a lot of knowledge on their own, there was so much knowledge that had been stripped away after passing through different hands, and there was still so much subtlety in the imagery to determine the integrity of what was being presented: how consentual were these portraits and how much of a role did the photographer have in constructing the narrative of the sitter—the dress, the posing, the accompanying objects? Through the IMLS project we were able to correct inaccuracies, privilege names, locations, objects, and activities using the Hawaiian language, and begin to create intellectual groupings of objects—both for purposes of accumulating meaning across images but also identifying possible sensitivities.

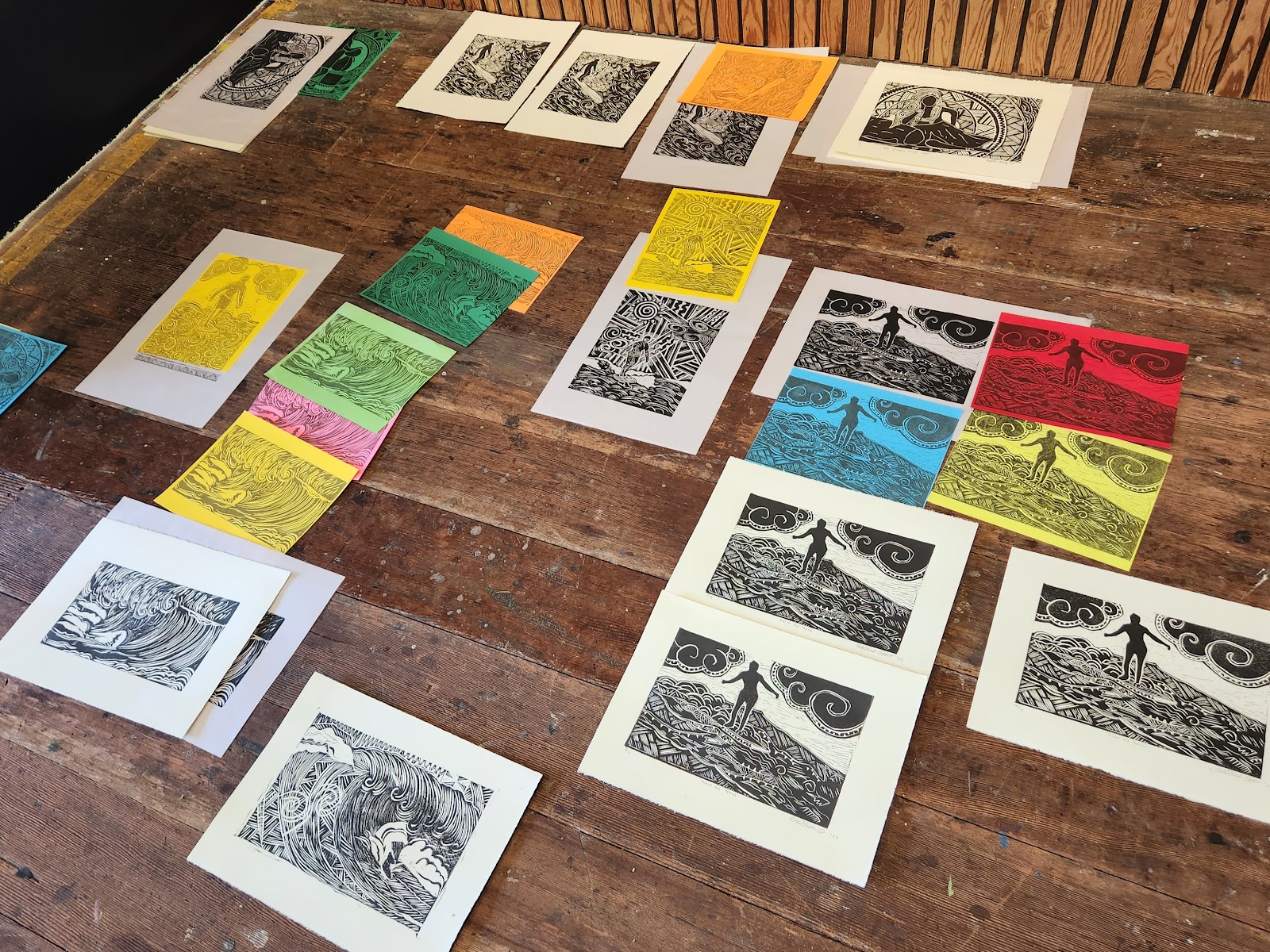

Other ways that this project sought to generate new life lines for the images in this “family album,” as it came to be called, was seen through Aotearoan artist-in-residence Michael Tuffery’s approach towards community. This can be seen in his work that spans decades and mediums as well as his commitment to education and working with youth to create intergenerational connections to kūpuna and to restore mana (life force, power). Using images from the collection (images of surfers and hula were particularly popular), students from the Hawaiian-language immersion school Ke Kula ‘O ‘Ehunuikaimalino created relief prints utilizing patterns found in traditional woodcarving techniques. In learning about past traditions and imagery and connecting them to contemporary memory, art-making became a means for accessing this inherent lifeforce. Seeing images from the collection as a conduit connecting the students to their ancestors felt especially meaningful and took it out of the often austere context of the museum. It felt like the way these images are supposed to be used.

So many other moments from the first few weeks of the exhibition come to mind as well. From artist Marques Hanelei Marzan’s dance and chants that he used during the opening to activate his beautiful hand-knotted cloak (‘a‘ahu pu‘ulei), evoking the dress found in several images in the collection, to artist Nainoa Rosehill’s bittersweet connection to Hoʻōpūloa, a village that was lost to volcanic flow depicted in the collection and where his great grandmother, Elizabeth Pakele Akamu, formerly resided, there was so much personal connection to the images to keep the stories alive. From Nainoa’s artist statement: “It is of both the people who have passed and of their heirs who still live. It is an intimate representation of the lava and its scions, whose cultural landscape is the body of the deities who embody the most powerful force in the Hawaiian archipelago. Above all, it is one story of the way lava shapes, not only the land, but the Hawaiian.” It's expressions like this that remind us that data that often accompanies these objects in museums is not only inadequate but only reflects a narrow and specific form of knowledge, and that there are so many other ways to pass these stories on.

More than anything, the several weeks I spent in Kona at the Donkey Mill reminded me of the importance of presence and embodiment, and connecting on a personal level and talking story with the community that surrounds this amazing community art space. As Halena Kapuni-Reynolds, scholar and Associate Curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, observed during the panel discussion, providing food at community events is paramount for these experiences. Gathering around and sharing food not only ensures that people will show up, but that we will find a number of ways to learn from each other and connect through what sustains us. This life force is also what connects us to the ancestors in these images, and reminds us that it was not too long ago that they were on this soil. More and more I am learning that collection stewardship is more about personal experiences and community than it is about the objects themselves. How else do these objects come to hold meaning if they do not continue to draw from this life force? I hope to take this knowledge into my work going forward and to continue to help these important materials to find the light again.

Mai Ka Pouli: (Re)presentations of Moananuiākea is on view at the Donkey Mill Art Center through July 8, 2023.