While visitors to LACMA may catch a glimpse behind the scenes during exhibition installations, less visible is the work that happens backstage to support a richer understanding of works in the collection on an ongoing basis. LACMA’s Department of Prints and Drawings holds a group of nearly 700 works on paper by the Belgian artist Félicien Rops (1833–1898). The collection, first amassed by etcher Alfred Taiée, is the only collection of Rops’s work assembled in the artist’s lifetime that remains together today, and the largest public collection of his work in the United States. As a USC-LACMA Summer Research Fellow, I spent the past two months examining this collection, specifically researching Rops’s enigmatic practice of employing photographers and printers to photomechanically reproduce his drawings as the background of his prints, over which he layered more traditional intaglio printmaking techniques. This kind of collection research helps curators to make informed decisions about how we classify and describe works, either for public access online or in the galleries.

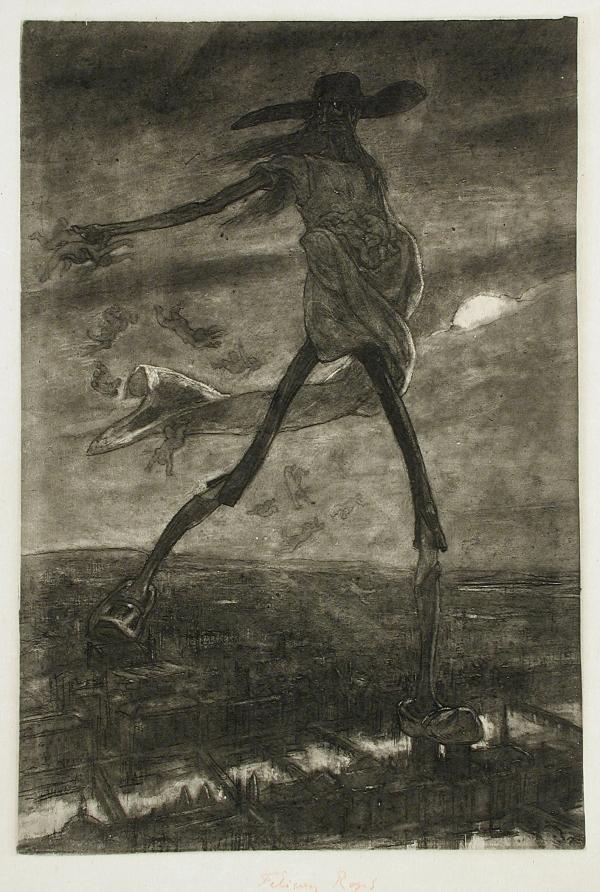

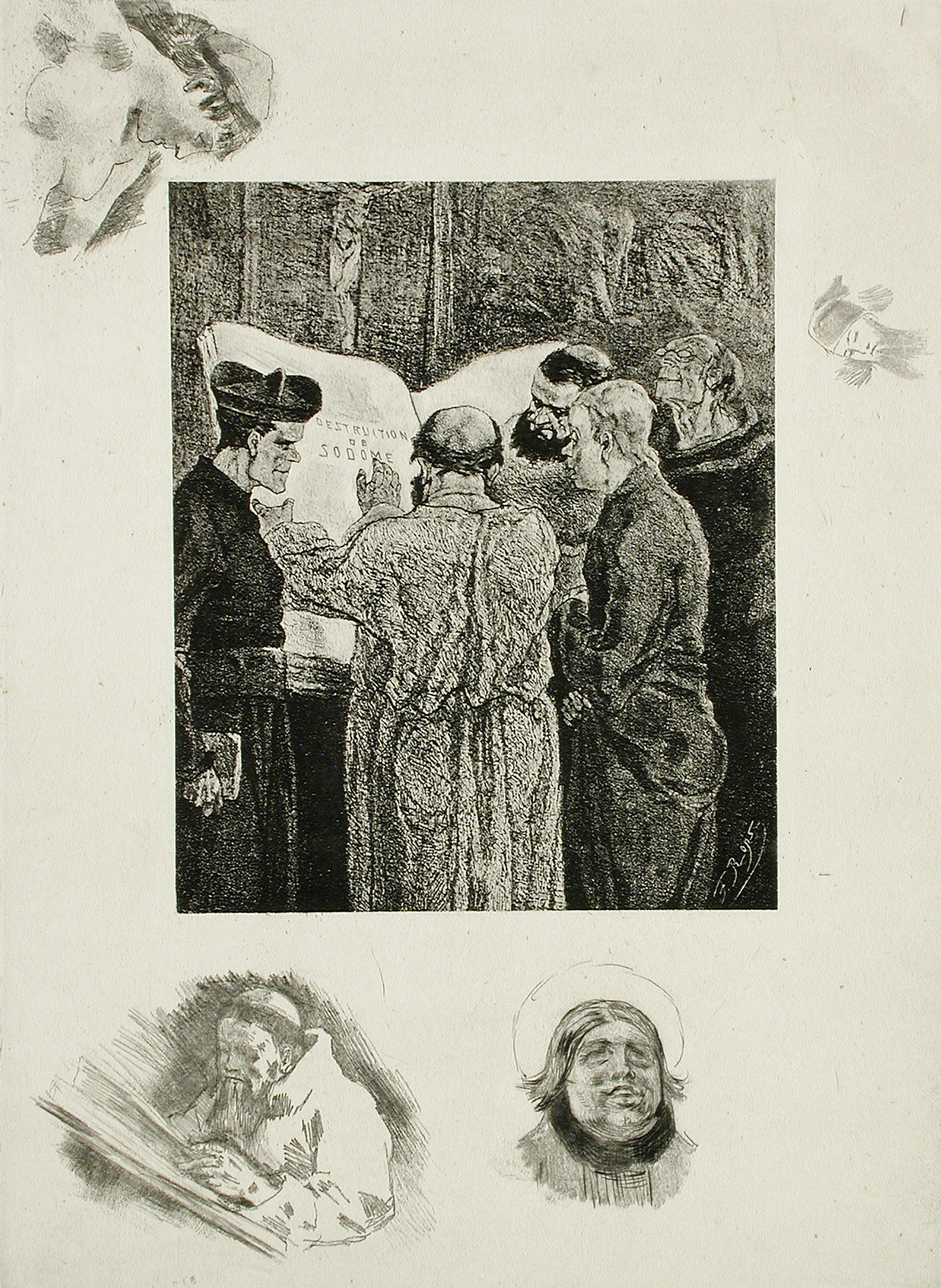

Born in Namur, Belgium, in 1833, Rops began to attract attention and notoriety in Brussels for his satirical and anticlerical lithographs in 1859. Turning his attention to intaglio in 1865, and regularly employing photomechanical processes in his work beginning in late 1874, Rops eventually settled in Paris, building a network of collaborators—writers, printers, publishers, and photographers—in France and Belgium. In Paris, he mingled with bourgeois bibliophiles, making a name for himself both as an experimental printmaker and as a draftsman of frequently pornographic subject matter.

When works by Rops entered LACMA’s collection between 1979 and 1984, many were classified as examples of various traditional etching techniques, such as soft-ground, drypoint, and aquatint, consistent with how these prints were described in period criticism and exhibition and sales catalogs during the artist’s lifetime. Yet looking closely at prints under magnification, sometimes alongside LACMA’s conservators, and cross-examining works with more recent scholarship and Rops’s letters to collaborators, revealed these descriptions to be repeatedly inaccurate. Some cases were simple, such as Tentation ou la pomme, which was classified as an etching, but is instead an unretouched photogravure (a photograph etched on a copperplate) reproducing a drawing.

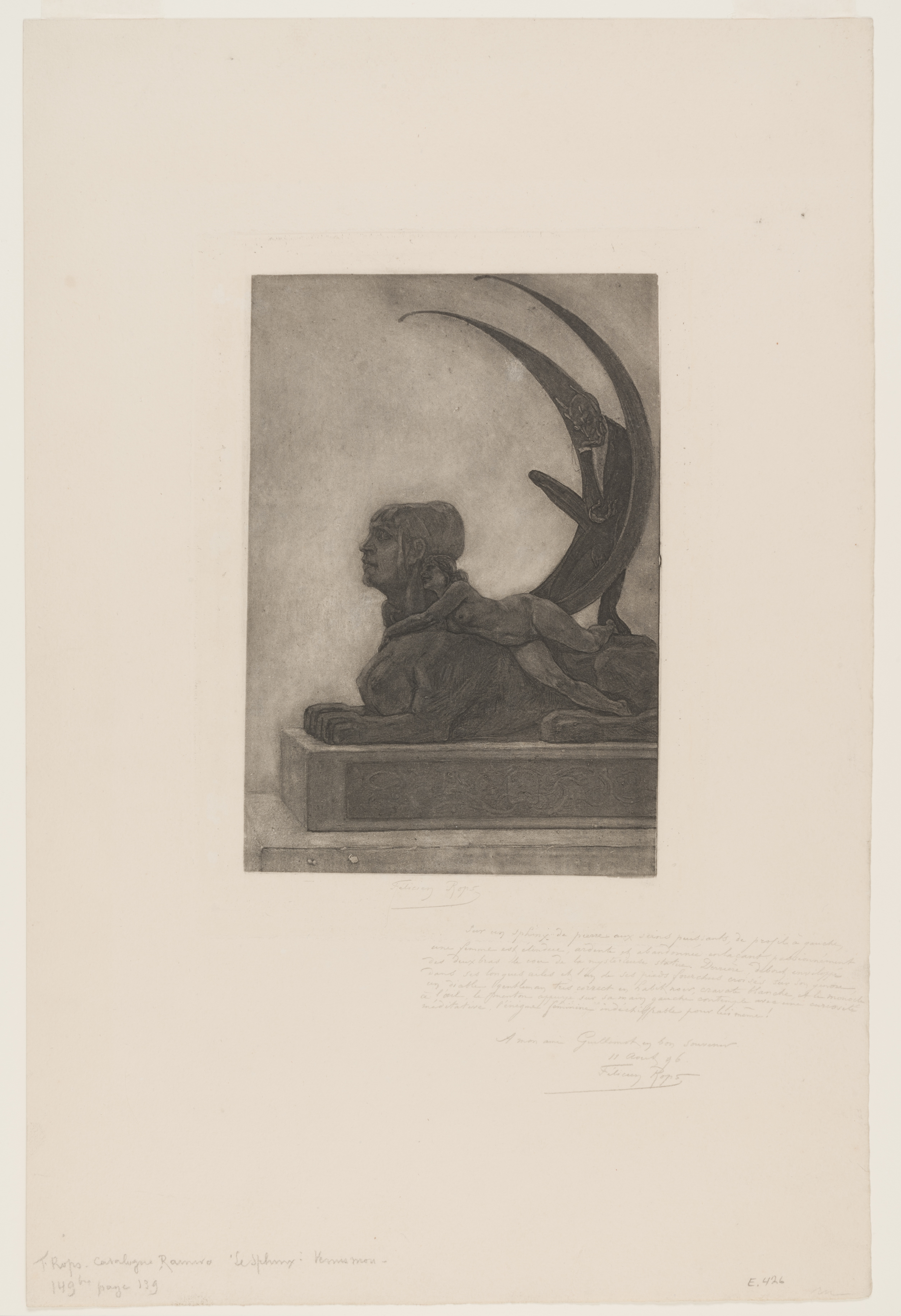

Other cases revealed more complex layering of different mediums and only tentative attributions, such as the fourth state of Le Sphinx (1882–83), which is likely a drawing reproduced as a photogravure, retouched with aquatint and soft-ground etching, and further etched by collaborating artist François Courboin. Le Sphinx materializes a whole cast of characters working collectively—an unnamed photographer who produced a film negative of the drawing, Courboin who retouched the plate, Alfred Salmon who printed the edition, Alphonse Lemerre who published the work, and Léon Evely who later produced larger photogravure plates of these compositions in 1888–89.

While intaglio printmaking is inherently collaborative, Rops would have preferred the photomechanical steps of his process to remain unaccounted for. Writing to frequent photogravure collaborator Evely in 1881, Rops underscored the clandestine nature of their work together: “please keep this a secret. You know the work of most publishers; if they know that photogravure is used, they do not know how we use it and they imagine that we make our plates entirely through the process, which in their eyes diminishes them of value.”¹ While Rops used photogravure to save time, to disseminate his drawings among his coterie, and to sell more prints, he remained furtive about this tool for financial and reputational reasons.

Reevaluating the language that we use in medium lines for Rops’s prints not only more accurately conveys to viewers how works are made, but also helps us to understand hierarchies of mediums and their corresponding values in the period that Rops was working. In this case, Rops’s use of photomechanical processes provides insight on the possibilities afforded by—and uneasiness that came with—mixing traditional processes of intaglio printmaking with the still novel medium of photography in France and Belgium before the halftone boom at the end of the 19th century.

1. Félicien Rops, letter to Léon Evely, January 14, 1881, Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique Cabinet des Manuscrits, Bruxelles, quoted in Maurice Kunel, “Lettres de Félicien Rops à Léon Evely,” Le Livre et l’estampe 24 (1960): 303. My translation.