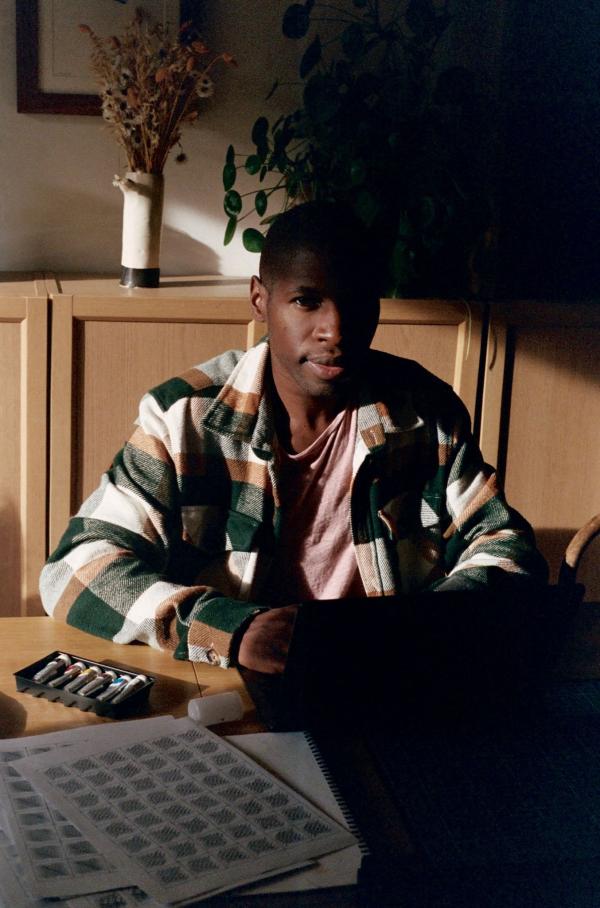

Cactoid Labs curator and co-founder Lady Cactoid recently sat down with artist William Mapan to explore his process, the stories behind the art he currently has on view at the museum’s Stark Bar screens, and the work he is creating in dialogue with LACMA’s permanent collection for the project Remembrance of Things Future, curated and engineered by the experimental blockchain consultancy Cactoid Labs.

Building upon LACMA’s historic engagements with Art and Technology, Remembrance of Things Future is an invitation to travel via the blockchain back in time through the museum’s encyclopedic collection. Utilizing tools such as generative code, Mapan, alongside other pioneering artists, has been invited to select objects from LACMA and make new digital editions inspired by the museum’s holdings. Released on the blockchain in phases, a percentage of proceeds from these limited Remembrance of Things Future digital editions goes to support LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab. More information on this project can be found at lacma.cactoidlabs.io.

Hi, William! Could you begin by telling us a bit about your background as an artist?

Hey, hello! My background is very chaotic I would say. As I’m a very curious person, I tend to want to explore everything. I started with a weird but perfect degree where we touched everything multimedia: math, design, art history, programming. I quickly fell in love with Flash, motion design, and programming. Then I started my career as a motion designer. Mostly Flash and After Effects. Very quickly, I wanted to optimize my workflows and started to use a lot of code alongside those programs. One year later, I just wanted to program all day long, but always with my graphic approach. So I started doodling a lot to merge both disciplines. I did a final degree at the world-renowned school of animation Gobelins, in Paris, where I discovered a new world: media arts. At Gobelins everyone was determined to change the world. Well, we didn’t quite manage that, but Gobelins did convince me to pursue my goal of combining code with graphics. It’s still one of my best experiences in life.

After Gobelins I worked as a creative developer in the advertising industry for 10 years. During that period, I started all kinds of other hobbies on the side, be it painting, photography, 3D, stop motion, pottery, weaving. I tend to have obsessive behaviors while learning things. I began to go to a lot of museums and galleries and fell in love with Abstract Expressionism. It was incredible to see these artists liberate themselves. Cy Twombly, Joan Mitchell, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, they really got into my skin. That’s when I started to want to create my own things inspired by them with code. I had been experimenting with creative coding for awhile when I finally stumbled onto the work of generative art pioneers like Georg Nees, Herbert Franke, and Vera Molnár. I think in 2017 or so, was when I was able to put a word on all this. It was echoing what I was doing in my little corner. After that, a whole universe just opened before me. And I am just constantly observing, and not just visual art. Music, hip-hop especially, has been proper fuel all my life. People I can identify with, like Kendrick Lamar. Musicians have to put themselves out there and take risks. There’s no screen to protect you. You have to show up and be true to yourself.

When we first began working together on this project with LACMA you were thinking about materials like plaster and stucco. We were looking at sculpture in the museum’s collection and you were developing work that was very pared down in terms of color palette, just white and gray. Then you came across Paul Klee’s In the Kairouan Style, Transposed in a Moderate Way, from 1914, in LACMA’s collection and immediately were captivated. What drew you to this watercolor by Klee?

I think it was the interplay between the composition—which is grid-based and potentially very rigid—and the color, which is harmonious and soft. Watercolor is interesting because it is so fluid and loose. It’s able to break the grid. I wanted to explore that.

At first I didn't see it was Paul Klee. When I realized it was him, it made a lot of sense. Then when I saw that Klee painted it in Tunisia, I began to think about the work in terms of travel: new environments, new lenses, about what travel means to me. To reflect on aerial views, what places look like from the sky. The series is called Distance.

It is related to my experience. I grew up in the suburbs of Paris. Then when I was 16 we moved to a small village near Pithiviers of 800 people. That is where I learned about nature, about the beauty of the land. I would drive for hours in the countryside, and stop and look. This fresh air, what you see in front of you, is very big. You don’t experience that in the city, where the horizon is always cut by a building. It changed the way I view the world. Before I lived in the countryside, when I was on a plane, I would look down at the ground below and just see patterns. After moving to the countryside, these aerial views began to really talk to me.

Travel is like being constantly awake, constantly aware. I feel that state now. I am constantly trying to be aware now of how my environment affects me. In that way, travel is a chance to reflect on your life as a whole. This series is about standing back from what you see. I was reflecting on my past works and it is always about my personal experience. I think it is about seeing the bigger picture.

The watercolor you selected from LACMA was important in Klee’s oeuvre. It marked a turning point from figuration toward his first fully abstract creations. He painted it in Tunisia, then under French colonial rule, where the light of the North African country and its effect on the perception of color had a dramatic impact. “Colour possesses me,” Klee wrote. “It will possess me always, I know it. That is the meaning of this happy hour: colour and I are one. I am a painter.” When we visited you in your studio in Paris I was fascinated with your very rigorous approach to color. Could you speak about your relationship with color?

I was excited to find the Klee work at LACMA. It was a bit like a teacher-student thing. I was familiar with Klee’s color theory and really admire his use of color. Everything is harmonic, his colors are not too hard, not too desaturated, and everything is nicely in place. I was very interested in why that was. Being a former developer, the science of color has always made a lot of sense to me. I naturally went deep into color theory. Color is a very strong language, even without composition. You can say things with color. It is the main component that I think about as an artist. How you use saturation, the value of the color, how you mix it. I always try to make the colors I use.

So for instance, I often take a composition that I created with JavaScript on the computer and translate that image to gouache on paper. When I do that, I am translating colors created with code to physical paint. I don’t allow myself to just go to the store and buy a tube of the magenta color I created with my code. I force myself to mix the color using only the primary colors. That is all you really need. So I have my tubes of red, blue, and yellow and I work with them until I can get the right ratio of each color and finally arrive at the pigment I am trying to replicate.

We have too many things nowadays. Things come too easily. If I am at the art store, I could simply say, oh, I like this color, I am going to buy it. But if I do that, I don’t build a relationship with the color. I like to go deeper, to understand my colors. I like to know what they are made of. I think it is important. A color is not just a color, it is much more, it means hard work. It means relationship. It means emotion. When I create a color, I know the mood I was in when I created it. I only allow myself to buy a tube of premixed paint after I have learned to make it myself. So even if I buy a tube of this color, when I buy it, I have memories of me creating the color. It is a good way for me to have a conversation with my art.

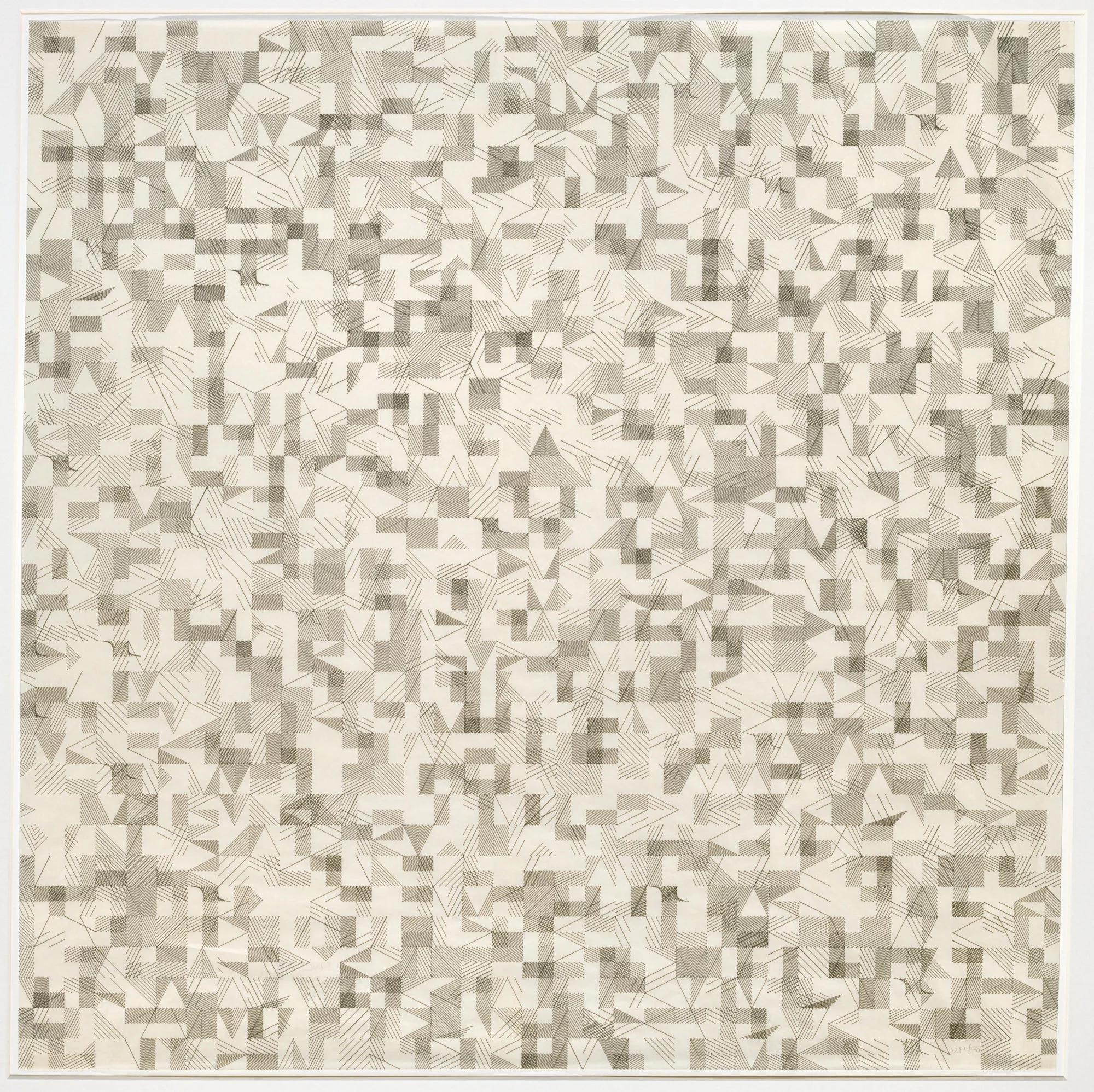

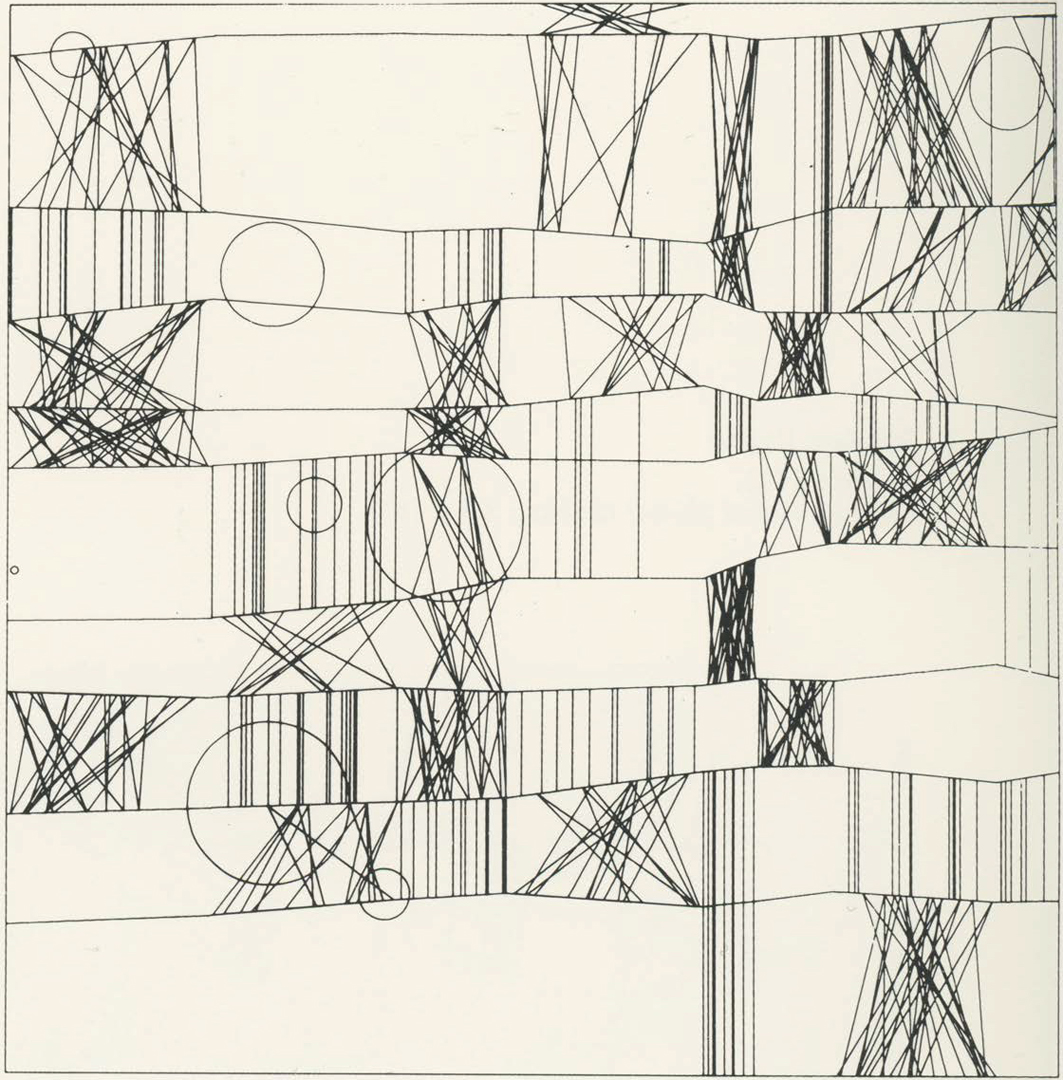

It is interesting that some of the pioneers of computational art like Vera Molnár and Frieder Nake also created works inspired by Paul Klee. That is something that came through in LACMA’s recent exhibition Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, which included works such as Vera Molnar’s 1971 piece À la Recherche de Paul Klee. What do you make of these earlier experiments?

Both Molnár and Nake, the first thing I think they saw in Klee was the composition. Not the colors, but the composition. Because the logic of the grid is very strong in Klee’s work. And of course the grid, the X and Y axes, are foundational to code-based art. The grid is what struck me first too, and then the colors that were sublimating the composition.

Both Nake and Molnár's Klee-inspired works are devoid of color. I wonder if that speaks in part to the realities of working with mainframe computers in the 1960s and 1970s?

Yeah, they didn’t have the computational power to process a lot of data back then and I imagine that played a part in the minimalist nature of Molnár and Nake, that limitation of the technology. But it is very interesting because when you are limited you need to be very demanding. In some ways it was more interesting, since you had to extract your core idea, versus today: when you add more complexity and power it gives you more tools in your tool box, but it is not easier, it gives you way more noise. I think that is why I don’t like to use a lot of libraries in my code. I don’t like to use a lot of high-level programs. JavaScript is enough for me. For now, I don’t really feel the need to use another super fancy library on top. Maybe later, who knows? As soon as you have too many things, you are constrained by a sea of tools, but if you need to build your own boat out of a tree then you can make a very custom boat. I like to keep it simple, complex but simple.

I am laughing here because I look at the code you write and the layered and painterly compositions you create and it all seems very complex. So much of our relationship with computers, and that goes for our relationship with generative art, can seem like magic. You write some instructions and, voilá, here we have these beautiful colorful forms on the screen. But how do you build up your canvases? What is that process like?

Basically, I like to paint. I have this strong relationship with pigment and paint. Once I developed a strong capacity to code, coding became a way for me to translate what I can do with my own hands, and to expand that to infinity through the computer. To make a system with parameters. With the computer I can repeat the same shape a hundred times and experiment with what happens when I do that in a very ordered way, starting from the bottom, left to right, et cetera. I try to have very simple rules, but a lot of them, that will create textures that can speak to me. In this series I did for LACMA I have very distinct sharp shapes and that is my way of saying that this is still digital. I tried to restrict myself when looking at the Klee, to only use squares, rectangles, and circles, and to see what I could do with that.

Watching you evolve the algorithm over these months I see how the process itself of generative art is an important part of the work.

It is hard to explain. It is very messy. My code is very messy. It is always something new that I am looking for. I don’t really like to have my nice little starter but rather start from scratch all over again with some helpers functions. Not very recommended for programmers, but it is what it is! As I work, the code evolves and becomes better as I index the properties I am creating. When you paint you lose yourself, and I try to have this with the computer, which is very predictable. Give me a row of 10 circles, and you get a row of 10 perfect circles. But I am used to doing things by hand. I feel uncomfortable when I draw perfect shapes, perfect outlines, so I try to make it more alive according to my experience. I use a lot of shaders which can be hard to grasp. When I start with a blank canvas, it is like then I am going to throw some paint, then stretch it around. Or, if it’s wet or dry impasto, I am going to try to translate that into code, and in the process of coding I am going to find new stuff to try. So I will experiment with water.

How do I make fluid behavior with code? When I paint with gouache, I paint with many layers, which adds more and more thickness to the paint, and all those properties I am going to translate to my code, like layers in Photoshop. More and more layers until you can’t see what is going on. I sort of feel like I build my own spaceship and I am an astronaut exploring the unknown. The more you work on your system, the more the space expands, the more questions arise, the more patterns. You can learn more about how things work, how things look. That is the magic and the joy I find in generative art. I am quite excited for people to discover this new body of work created for LACMA!