“What happened to the people that built Maya temples?” “Do Indigenous communities still exist?” “Who are the Indigenous people of Los Angeles?”

These are just a few earnest questions our educators within LACMA’s Mobile Programs encounter as we visit middle schools throughout Los Angeles County. For every student wondering if Indigenous cultures still exist, however, there are students who have studied Indigenous cultures, as well as those excited to share that they have Chumash or Tongva ancestry, relatives who speak Zapotec or K’iche Maya, or relatives who participate in ancestral dance or cooking groups. In establishing a space where students can share these perspectives, our school program has created two Practical Guides to teaching cultures of the Early World and the Ancestral Americas. For Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we’re sharing some of the ideas utilized in our program and discussed in these guides, such as creating a brave space for students and using object-based learning to discuss prevalent misconceptions about historical topics. (A brave space is similar to the concept of a “safe space” with an emphasis on encouraging students to not just feel safe to express ideas and experiences but to actively participate.)

We typically set the tone for our workshops with a Land Acknowledgement and discussion of Community Agreements. This Land Acknowledgment starts with a look at a map of the United States, followed by a map from Native-Land.ca, which overlays the approximate boundaries of Indigenous nations and communities. We then zoom into a map of Los Angeles County and overlay the boundaries of Tongva, Tataviam, Kizh, and Chumash communities. This exercise offers students a visual example of the different Indigenous groups within the U.S., as well as an emphasis that these communities are still alive and that some of the students at their school might have Indigenous heritage.

We then co-create Community Agreements by asking students for examples of what respect looks, feels, and sounds like to them. As they share, Mobile educators emphasize that they value students’ ideas, questions, and prior experiences.

These agreements are implemented during our object-based learning component, where students can hold and analyze objects from LACMA’s Art of the Ancient Americas collection. Rather than bombarding students with information that might be disconnected from their experiences, we have them discuss what they see, think, and wonder about the object and what they see on the object to support their ideas (based on VTS, and a study from Project Zero at Harvard Graduate School).

For example, as students observe the following object, some make comparisons to a molcajete—a mortar and pestle used to grind materials into guacamole and salsa—a tool they might have seen in a relative’s kitchen if not their own. To support this theory, they look at the grooves and evidence of use in the center of the hard stone, as well as the way the object seems to have small “feet” so that it can stand. Indeed, this metate was similarly used to grind corn and grain into masa or flour. This launches students into a conversation about ancestral foods, many of which are still prepared and enjoyed today in their homes.

Through these Object Handling workshops, classes can discuss ideas that dispel misconceptions about Indigenous communities. These groups did not just belong to the past but are a part of their modern lives and experiences through names in their community (Pacoima, Cahuenga, and Tujunga are all Tongva in origin), their foods, and their very own faces. When students observe objects with faces, they sometimes joke that it looks like one of their classmates. The students at the table start to laugh, but we note that they are seeing recognition in that object—rather than seeing a generalized or stylized face, they see familiar features looking right back at them. They see a little bit of themselves.

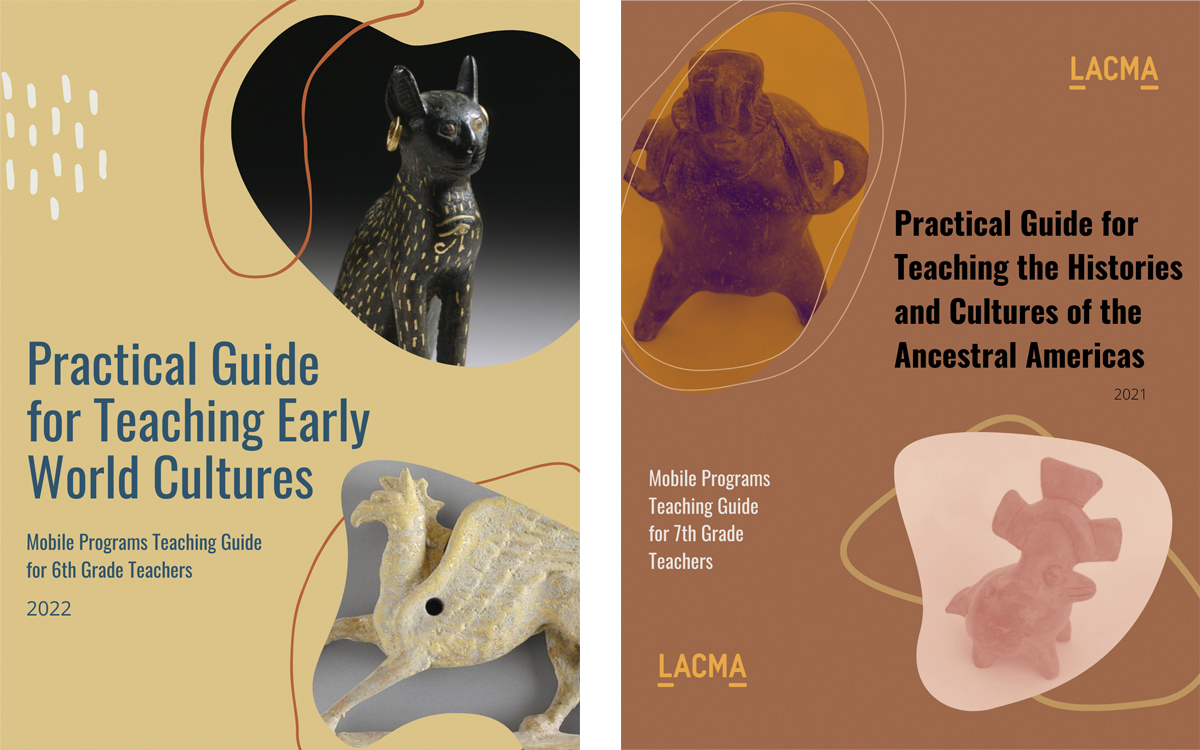

By setting the tone through Land Acknowledgements and Community Agreements and offering opportunities for students to share their experiences with object-based learning, we can enrich our understanding of Indigenous cultures, past and present. More information about these techniques can be found in the Mobile Programs Practical Guides for Teaching Early World Cultures and the Ancestral Americas. More information about the Mobile Programs can be found on our School Partnership Programs page.