If you search for a painting in LACMA’s Collections Online, you will usually find an image without its frame. For many artists in the 19th and 20th centuries, however, a consideration of the frame—its function and aesthetics—was integral to their conception of making and exhibiting art. Modernist painters challenged the Renaissance notion of painting as a “window onto the world,” in which the frame was an important “finding and focusing device” used to enhance a painting’s sense of depth.¹ As Western artists of the early 20th century rejected mimetic representations of their surroundings and instead addressed aspects of modern life, they also cast aside the ornate, gilded frames then still popular with many art dealers and collectors.

In 1905 a handful of architecture students in Dresden, Germany, formed the artist’s group Die Brücke (The Bridge), aiming “to attract all revolutionary and fermenting elements.”² They sought to channel their “creative drive directly and genuinely”³ and to create a new mode of expression that existed outside of traditional academic style, in direct challenge to Victorian socio-sexual mores and bourgeois standards of taste. Roughly applied paint, visible brushwork, and the application of non-naturalistic, often jarring colors characterize the paintings of Brücke artists like Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, and Max Pechstein. With a sensitivity to spatial relationships rooted in their architectural backgrounds, they typically made or designed their own frames, tending to favor what Kirchner called a simple Bretterrahm (plank frame). Unadorned and stained, either to contrast or intensify the painting’s color palette, the wooden frame became a part of the compositional whole.

Last spring, we had the opportunity to walk through LACMA’s Modern Art Galleries with Werner Murrer—an expert in Expressionist and early 20th-century frames whose Munich-based workshop Werner Murrer Rahmen houses a collection of over 100,000 archival photographs and more than 2,500 vintage frames—and discuss our goal of reframing several works. Our German Expressionist paintings, which entered the collection as early as 1946, had frames that reflected a variety of tastes and trends over the decades, rather than the artist's original vision. For the project, we decided to reframe seven of our most important German Expressionist paintings, five by Brücke artists Kirchner, Heckel, and Pechstein, as well as works by Ludwig Meidner and Otto Dix. Based on the paintings’ dates, historical documentation, and each artist’s particular style and framing preference (pine, for example, was Kirchner’s preferred wood) Werner Murrer Rahmen retrofitted three early 20th-century frames and created four replicas of original frames.

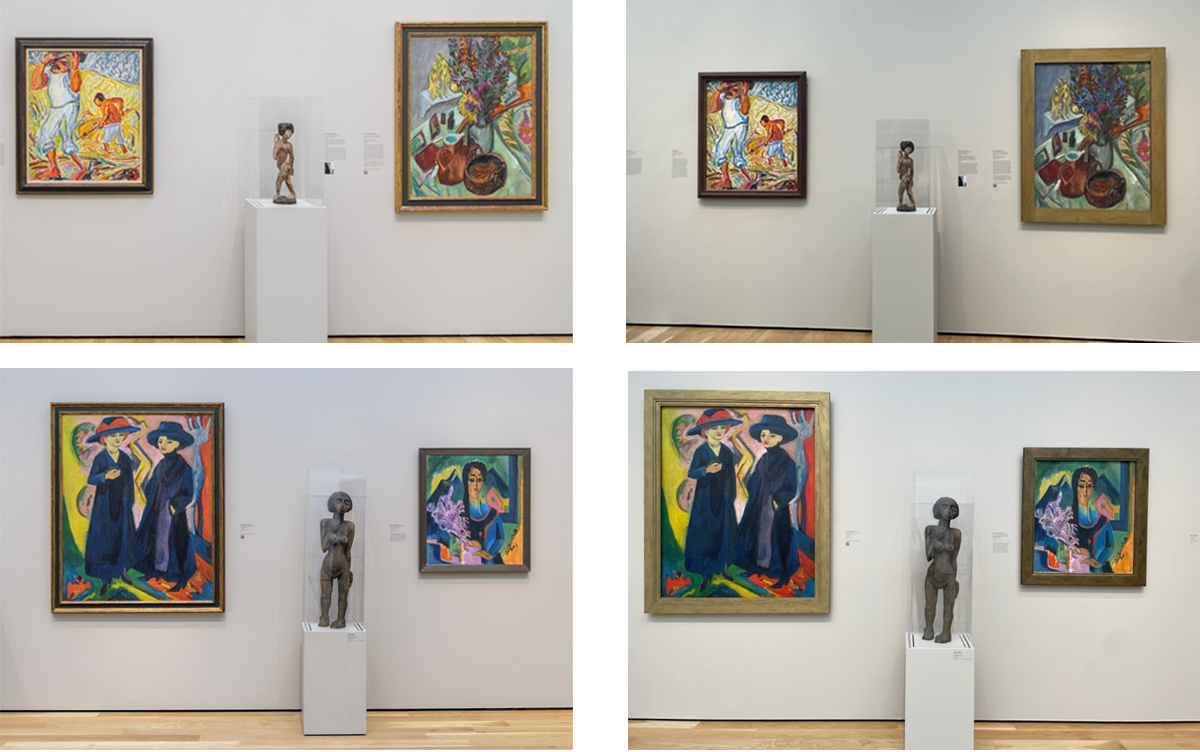

Based on installation shots of a 1923 exhibition at the Kunsthalle Basel, Murrer and his team were able to reconstruct a frame for Two Women modeled on this century-old original. By 1922, the second dating of the painting, the artist had moved to Davos, where he had sent his early canvases, rolled up and in need of new frames. The replica frame, modeled on what the artist himself would have designed and built, now reanimates the painting, bringing Kirchner’s artistic intentions back to life.

After meticulously measuring our seven paintings for the frame workshop in Munich, months later Joanne Harris, Assistant Conservator at LACMA, fitted them in their new frames. Fortunately all the careful measuring, endless emails, and testing samples worked perfectly! One by one, as our teams hung the paintings, I saw details come to life that previously hadn’t captured my attention.

The Expressionist painter Ludwig Meidner never belonged to a major artistic group like Kirchner or Heckel, but his explosive scenes presaging World War I, like Apocalyptic Landscape, bear the hallmarks of shared interests: the potential alienation of the modern metropolis, compression and fragmentation of space, and painterly pathos. Although little is known about Meidner’s framing practice, this frame from the early 20th century, which has been modified for this painting, lends the bold, graphic lines of the composition even greater force, the claret trim and black planks further emphasizing the flashes of chestnut punctuating this composition.

The unadorned frame with a slight bronze finish around Kirchner’s Still Life seems to remove any distractions. The echo of the artist’s staccato, gestural application of blue paint in the flower petals and the lines suggesting volume on the floor rug to the right, in turn emphasizing Kirchner’s experimental collapsing of space, now draws my attention. The visible grain of the frame's wood also suggests the significance of this material for Brücke artists, who carved wooden sculptures and experimented with woodcut prints.

The sloping curvature of the wood now hugging Pechstein’s Sunlight captures the natural light in the gallery, highlighting with the artist’s use of light to dapple the two female figures, enlivening the composition and underscoring its sense of immediacy.

This painting by Erich Heckel was exhibited at Galerie Arnold in Dresden as part of its 1910 exhibition on Brücke artists. From extant installation shots, we can determine the kind of stepped-profile frames Heckel would have used in 1909, thus offering excellent points of reference. In its new frame and without the previous ecru liner (popular with collectors and art dealers in the 1950s), the canvas now directly abuts the frame’s edge, which helps draw attention to the artist’s compression of space and the monumentality of the figure in the foreground, laboring under greater weight.

As the above images convey, with greater historical accuracy, frames and paintings can exist in concert. The frame acts less as a functional, protective boundary between the painting and the surrounding wall and instead serves as an extension of the work itself, more seamlessly connecting the painted canvas to the painted frame, lending the work greater visual impact. We invite you to return to these German Expressionist favorites and see the impact for yourself.

These works are now in view in the Modern Art Galleries in BCAM, Level 3.

This project was supported by the Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation.

1. Meyer Schapiro, “On some problems in the semiotics of visual art: field and vehicle in image-signs,” in Simiolus 6, 1 (1972-73): 11.

2. Karl Schmidt-Rottluff to Emil Nolde, letter dated February 1906, in Emil Nolde, Jahre der Kämpfe (Berlin: Rembrandt Verlag, 1934): 90.

3. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Programm der Künstlergruppe Brücke, 1906, https://collections.lacma.org/node/2302596