In February, LACMA acquired a vintage, early 1970s wire piece by the post-minimalist artist Richard Tuttle. Unlike most works that enter the museum, this delicate conceptual sculpture, composed only of thin wire and graphite line, did not arrive by crate or truck. Instead, the site-specific piece needed to be constructed onsite, and for the first time in his decades-long career, the artist wasn’t the one making it.

The Challenge of Preserving a Tuttle

As an artist who came of age amidst the rise of Minimalism—an abstract sculptural movement defined by austere, hard-edged geometric forms—Tuttle has, from the start of his career, created artworks that draw power from suggestion and restraint. Working with humble materials such as paper, string, cloth, and wire, Tuttle’s intimately scaled objects are distinguished by their emphasis on fragility and impermanence over monumentality.

Tuttle’s breakthrough came in 1965 with his radically minimal Line Pieces—wall drawings made with just a single stroke. These deceptively simple works marked the beginning of his ongoing, career-long exploration of line as the primary form of expression.

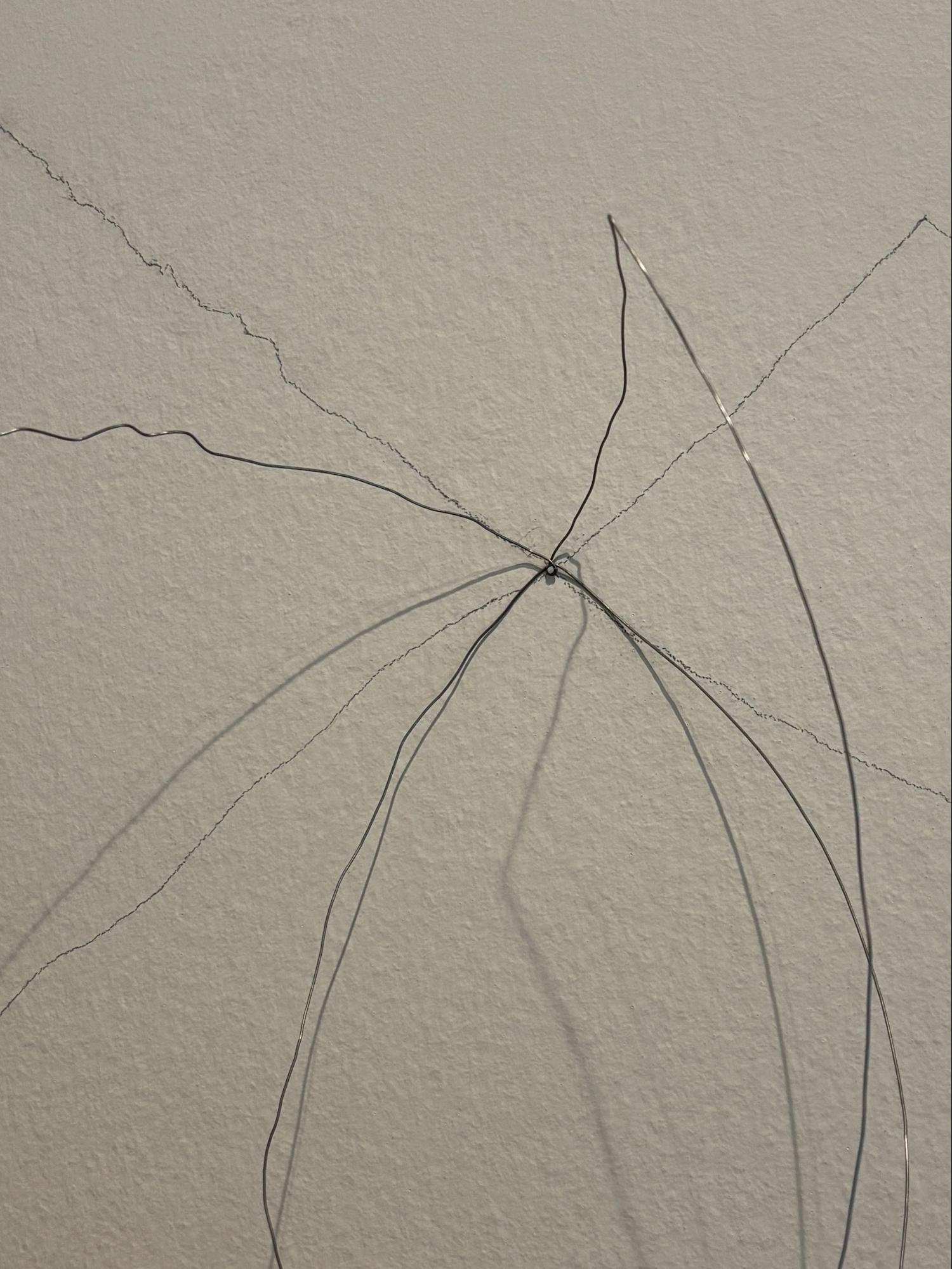

His wire sculptures brought this exploration into three-dimensions, transforming drawn line into sculptural form. Since 1971, Tuttle has created each wire piece himself through a quiet, almost balletic choreography. Barefoot and holding a pencil, he draws directly on the wall in a single, fluid motion, guided by the reach of his arm. He then traces the line with thin floral wire, allowing it to lift from the surface, introducing a third element—shadow—into the composition.

Because the works have, until now, taken the measurements of Tuttle’s own body as their starting point, curator and museum director Madeleine Grynsztejn once observed Tuttle’s Wire Pieces “suffer the very real risk of extinction.” Acquiring the work meant confronting the urgent questions it raises: how does a museum collect something that isn’t an object but an act of making?

1972/2025

The process of bringing Richard Tuttle’s Wire Piece to LACMA began with a phone call. Connie Tilton of New York’s Tilton Gallery reached out to the modern art department with an offer: she wished to gift the 23rd work in Tuttle’s 1972 series of 48 Wire Pieces. It would be LACMA’s first unique work by the artist, joining several prints and textiles already in the collection.

Senior curator Stephanie Barron and I took on the project, with Barron—who had navigated similar questions around Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings early in her career—encouraging me to take the lead. As a junior curator, the prospect was daunting but exciting. More accustomed to working with painting and sculpture than site-specific or conceptual art, I contacted colleagues at other institutions that had acquired Wire Pieces through similar channels. In every case, I heard the same thing: the work was always made with Tuttle present.

Yet, in conversation with the artist, the donor, and colleagues at the museum, we determined a better solution was necessary, a path forward for producing and displaying the wire work for many decades to come. We weren’t just preserving an artwork; we were preserving a method.

It soon became clear that to do so, we needed to embrace a model of distributed authorship in which the artist's gesture is extended through the hands of a community entrusted to sustain it.

In our conversations, Tuttle reiterated his desire to pass on the process of making his Wire Pieces—not just the technical steps, but the full physical engagement that had always defined them. He wanted someone to learn it directly from him. That responsibility fell to Dillon Ferenc, a LACMA preparator with experience installing site-specific conceptual works, including a recent Sol LeWitt wall drawing.

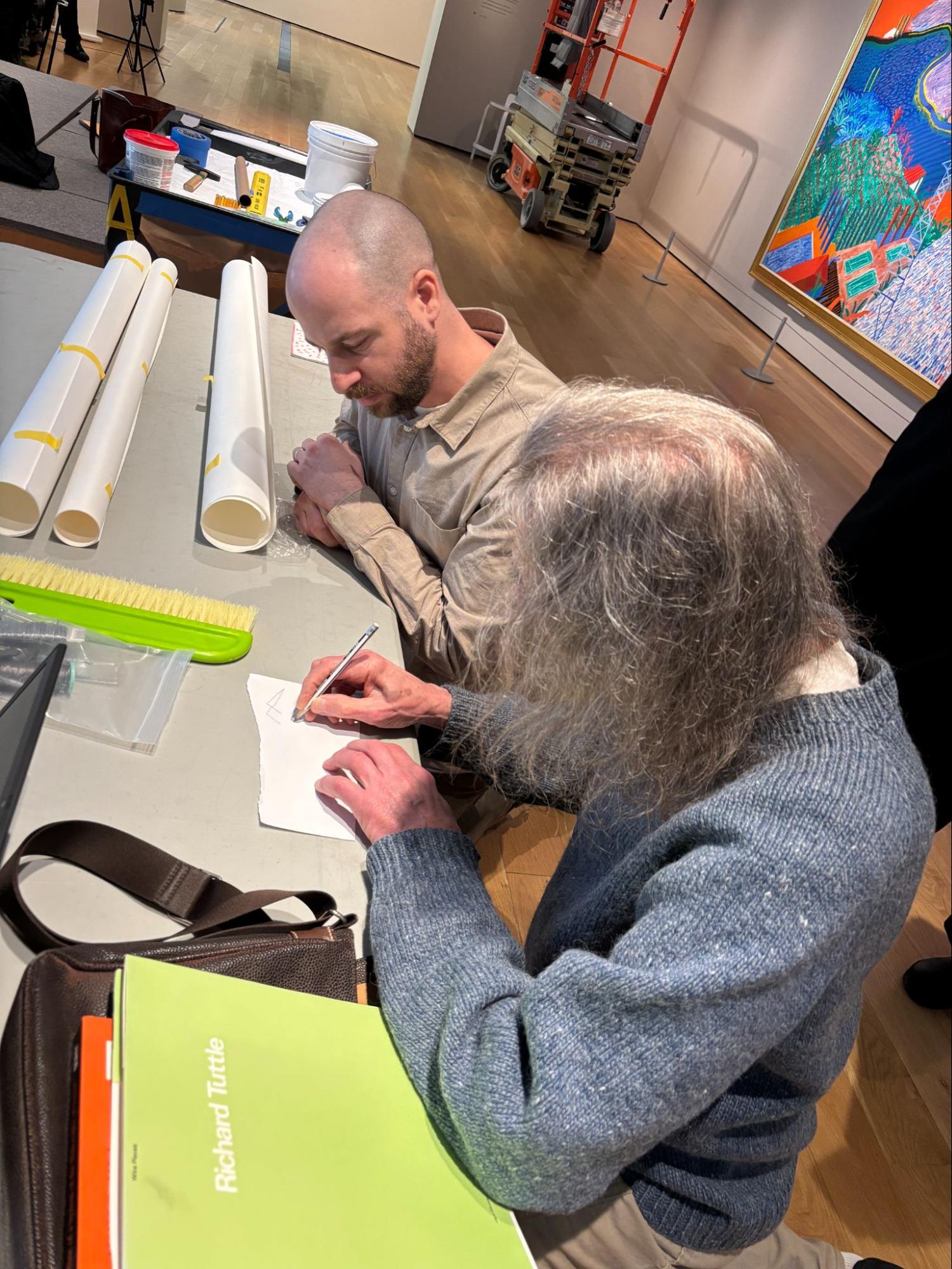

After months of preparation, I watched over two intensive days at LACMA as Tuttle guided every detail of the installation.

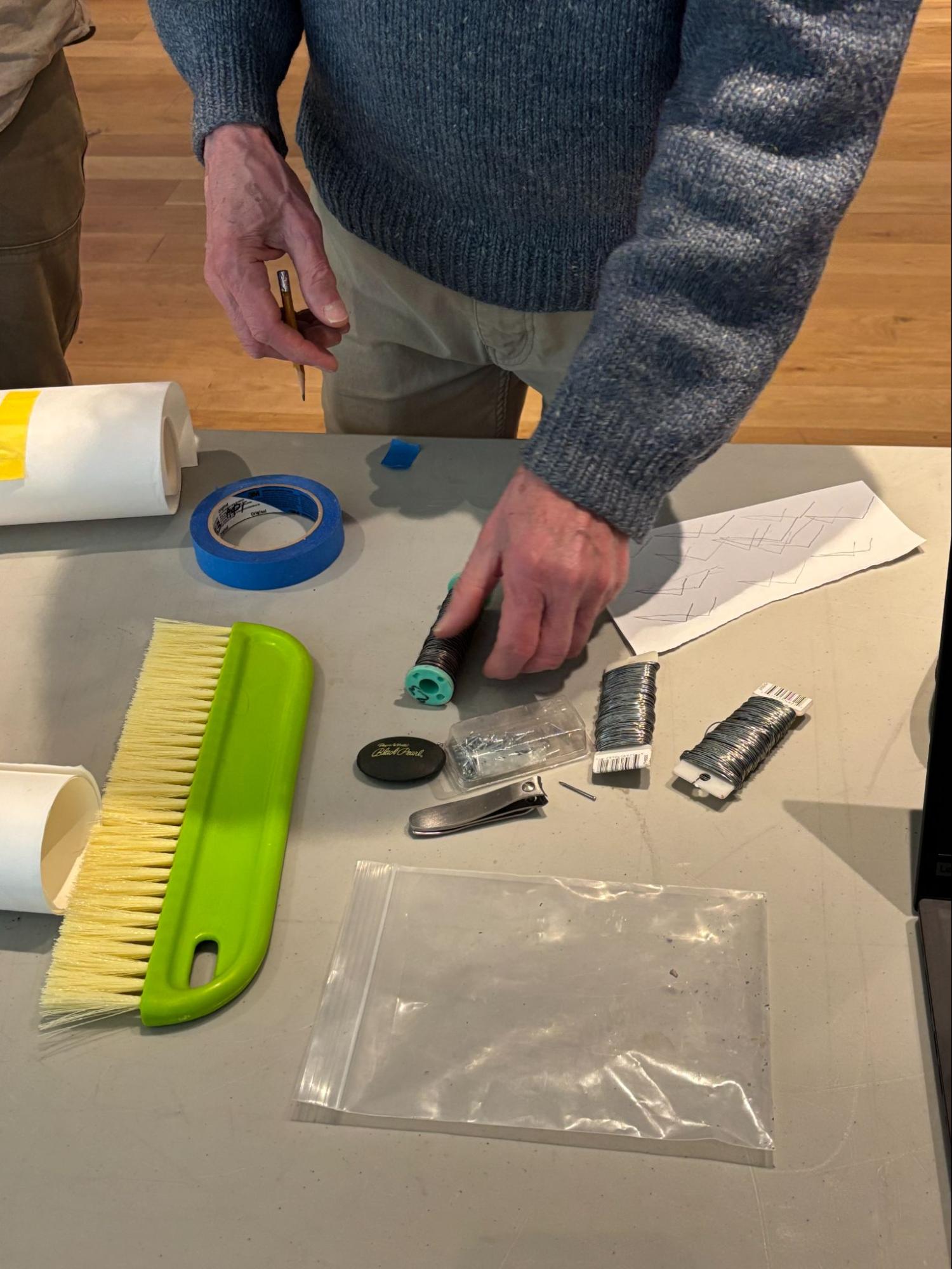

With our small group gathered—Barron and I, a permanent collection registrar, three audiovisual technicians, and Ferenc—Tuttle carefully explained his materials, demonstrating how each element shaped the work’s relationship to its environment. The process was unconventional from the start. Before making a single mark, he insisted that the wall be lit, not just to illuminate the work, but to activate the surrounding space, reinforcing the sculpture’s three-dimensional presence.

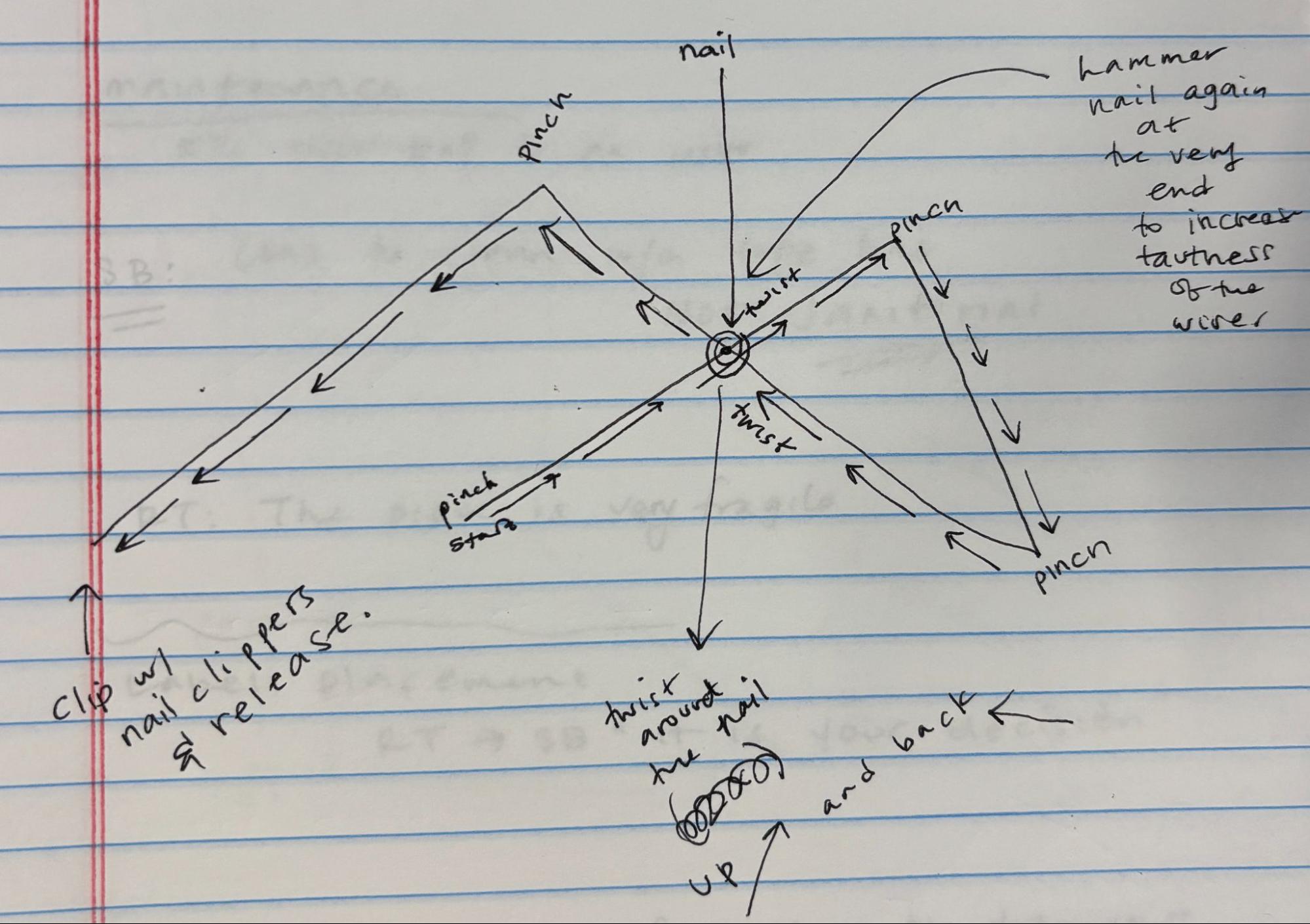

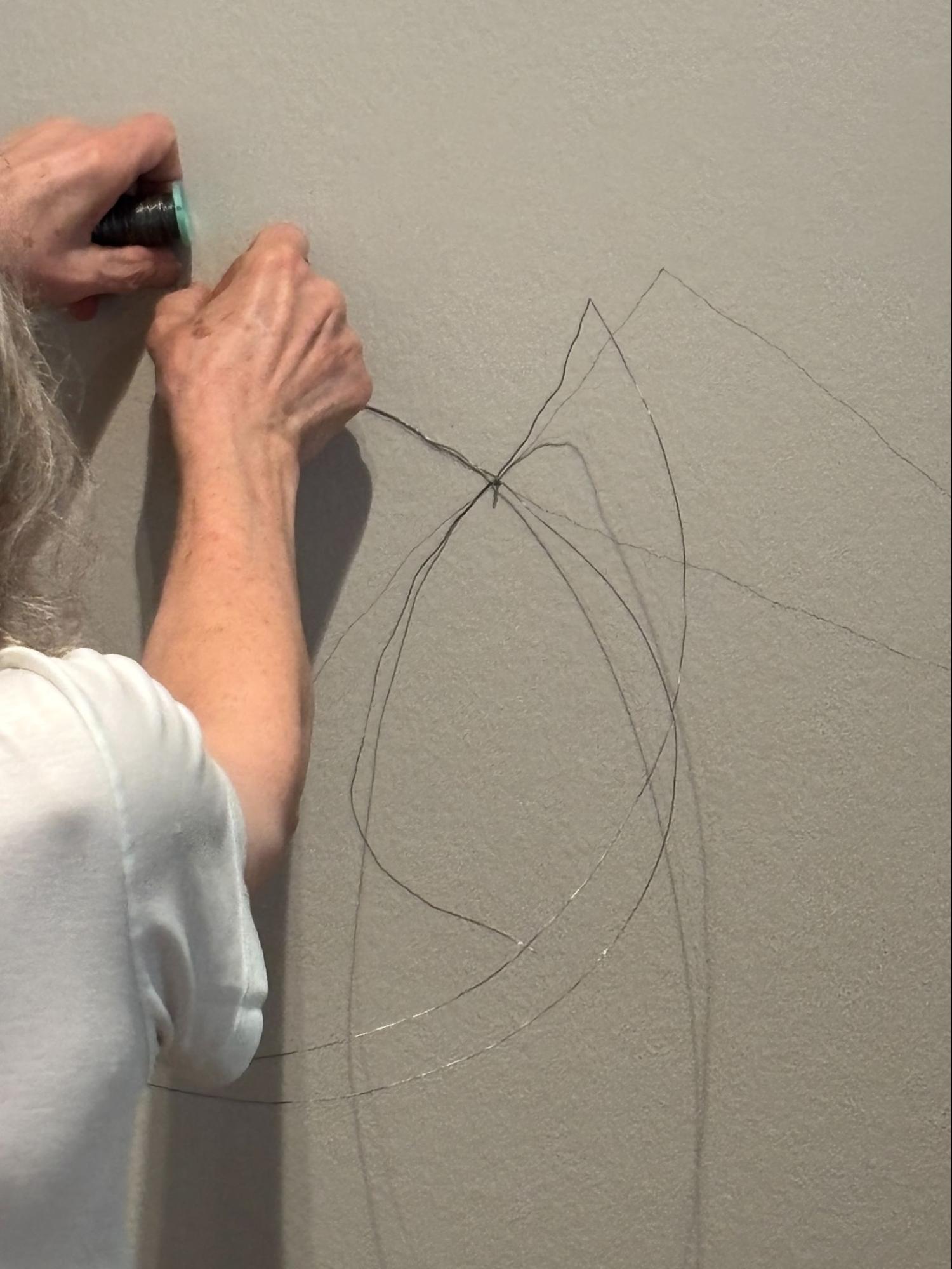

Then, as we stood by, Tuttle moved through each stage of the process with deliberate precision, making his own Wire Piece while narrating each step. He began with a simple gesture—the passage of a short pencil across the wall—laying down a graphite line dictated by the natural limits of his own reach. This became the kinetic root of the work, the foundation from which everything else emerged.

From there, the artist traced the line with floral wire, carefully guiding it along the drawn path, its movement shaped by the material’s natural resistance. Each movement was calibrated, each adjustment responsive. As Tuttle worked, what began as a static mark transformed into something active, hovering just beyond the surface of the wall.

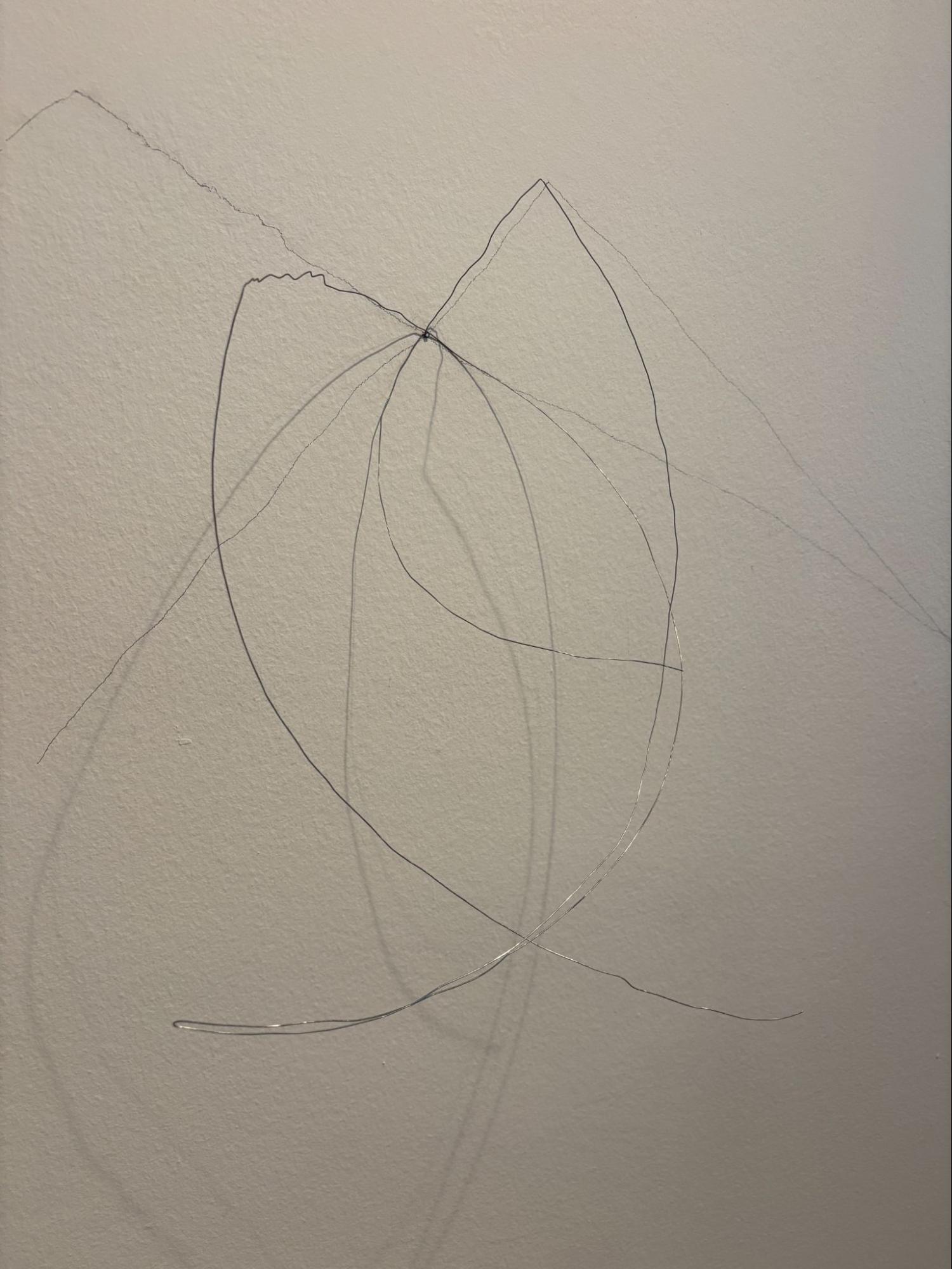

When it was time for Ferenc to make his Wire Piece, improvisation was key. Unlike in his role as a preparator—where precision is essential—the process of making a Wire Piece requires embracing the irregularities that come from working by hand, to let his own physicality dictate the wire’s final form.

Before leaving Ferenc alone in the gallery, in the private space of making, the artist issued one last instruction: keep toenail clippers in his back pocket for the final cut. He described this moment—the instant the wire is released to hover just off the wall—as “delicious.”

Upon returning to the gallery after Ferenc had completed the Wire Piece, Tuttle looked at the work with delight, noting that this moment represented not just a transfer of authorship, but a passing of the work from one generation to the next.

The New Life of a Wire Piece

For one evening only, during a public conversation with Tuttle, both wire sculptures—Tuttle’s demonstration piece and Ferenc’s—were displayed, unlabeled, on opposite walls of the gallery in BCAM, Level 3. Set in physical conversation, subtle but meaningful variations in line, tension, and shadow became clear. These weren’t mistakes or deviations from a set form; they were part of the work’s continued evolution that Tuttle embraced not as imperfections, but as evidence of the piece’s ongoing life.

And, when the final label was installed, it still credited Tuttle as the artist but also acknowledged Ferenc as the maker of this iteration. It was a small but significant shift, establishing a new way to think about authorship in Tuttle’s Wire Pieces. Later, Tuttle remarked that he viewed Ferenc’s version as a fully realized artwork unto its own, suggesting that this collaborative approach might shape how these works shifted and evolved in the future—tied to Tuttle, but taking on new life force upon each subsequent installation. Through this exchange, we became not just caretakers of Wire Piece #23 but participants in its continued existence.