Cactoid Labs’ curator and co-founder, Lady Cactoid, recently sat down with Kiya Tadele, the creative director of the artist collective Yatreda, in conjunction with the project Remembrance of Things Future, curated and engineered by the experimental blockchain consultancy Cactoid Labs.

Building upon LACMA’s historic engagements with art and technology, Remembrance of Things Future is an invitation to travel via the blockchain back in time through the museum’s encyclopedic collection. Utilizing the mediums of film and experimental, motion-based photography, Yatreda, alongside other pioneering artists, has been invited to select objects from LACMA and make new digital editions inspired by the museum’s holdings. Released on the blockchain in phases, a percentage of proceeds from these limited Remembrance of Things Future digital editions go to support LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab. More information on this project can be found at lacma.cactoidlabs.io.

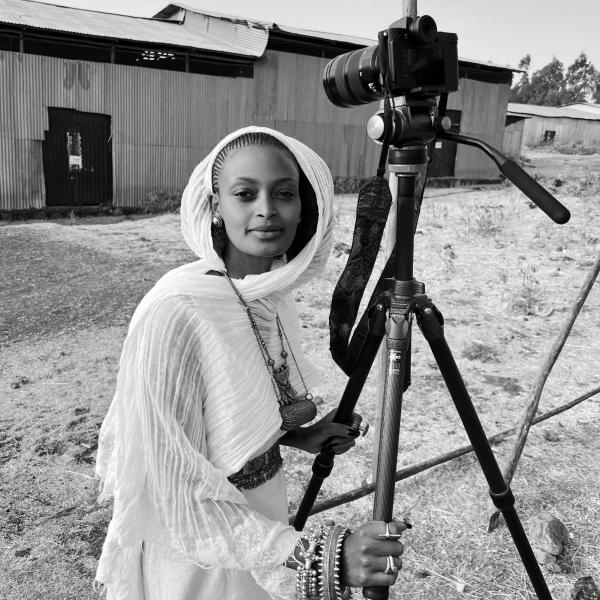

Hi, Kiya! Let’s begin with your artistic background. When did you pick up the camera and how has your approach to film and photography evolved over the years?

I grew up in the Ethiopian countryside where storytelling surrounds us, but I always saw a different life for myself as an artist. So I moved to our capital city, Addis Ababa, to pursue this feeling as a teenager. At that time it was not tied to any specific medium.

My first camera actually came to me by chance. It belonged to my brother, and at my cousin's graduation—he just handed it to me. The family knew I was the one always drawn to art. At that time I was modeling for others, and I started bringing the camera to fashion shows, taking photos of friends. It was playful, more like keeping memories.

After, I began studying photography properly at Master Academy in Addis, working in production for other photographers and filmmakers. I learned lighting, editing, and all the technical things. Joey Lawrence, my husband, has also been a great teacher. But it was always someone else's vision I was helping to create. I had my own ideas inside. In the beginning, the first Yatreda projects were simple. It was just our little family in the front yard, doing what each person could contribute. It was about costume design, character development, and then capturing the final result. I think of it more like a little local theatre.

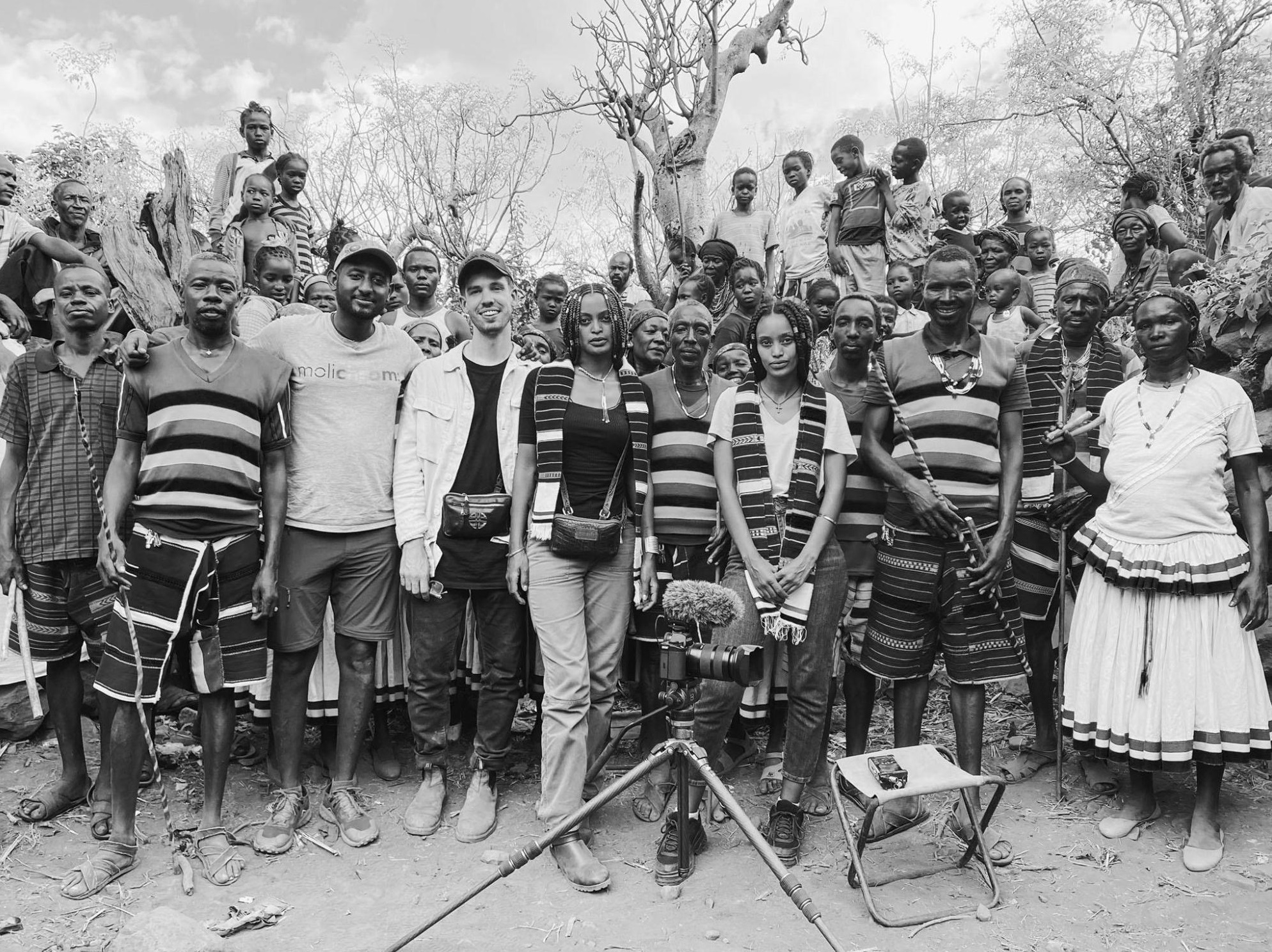

Everything changed when I minted the first artwork on the blockchain in early 2021, which quickly went viral. From that day, I saw it all as a real path for us. Now they've become these big productions across Ethiopia and Kenya. Lately, we have been experimenting with different mediums and storytelling approaches. Like immersive experiences. Photography or video can be what the final performance is captured on, but it's really about uniting all the elements. Everything comes together through the contributions of many people under what our audiences now recognize as the Yatreda style.

Your work is at once familiar, embracing the classicism of black-and-white portraiture, and surprisingly new, an innovative bridge between still photography and film, which I think resonates with our current gravitation toward video and the moving image. Could you walk us through your process? How do you create these arresting works?

Everything begins with an idea from myself or my sister Roman. It could be a folktale we heard as a child, an oral history passed down. But what's important is this question I always ask myself, "Where is the art?" Because just repeating cultural things, that's more like making an archive. What I care about is adding a dimension and a specific vision, something from my own heart that makes it alive today.

The research phase is deep. We read books, visit museums, and study old photographs. Then we decide who is strongest for each role. All of us do everything and anything to succeed. It could be cleaning dirt on our spinning 360 rig, or it could be placing a crown on our beloved cast member. My sister is a great designer, but sometimes we choose our Kenyan colleagues if they're better for that specific vision. When we capture the performance, my focus is always on directing the cast. Not just how they look, but how they carry the spirit of the character and how it relates to the original idea. The challenge is making all these pieces—the costumes, locations, lighting, movement—unite with what I call the Yatreda spirit. Not a movie, not a photo, but a living and breathing artwork. That's really my job, to be the guardian of that.

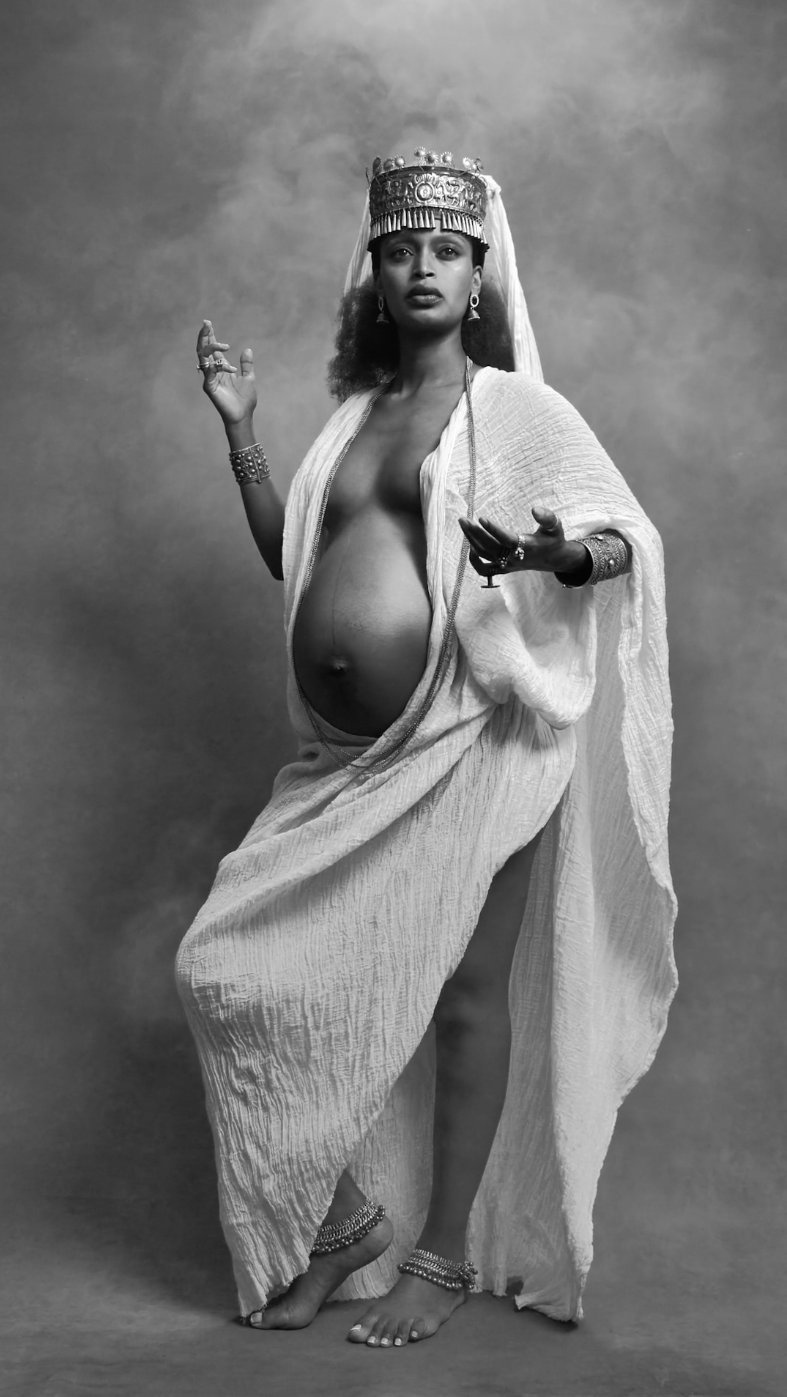

When we shoot, everything is done entirely in-camera. The smoke, the wind, everything is in a single shot with all natural light. We shoot in slow motion, at 59.94 frames per second, so that when we put it on a 29.97 timeline, it creates a liquid slow motion. Normal cinema is usually at 24 frames a second, but we like the unique smooth looking video quality of 29.97 for this kind of artwork, since it is not really a movie, and needs to take us to a different kind of visual world.

Back home, I'll go through hours and hours of footage, sometimes searching for the few seconds that are perfect, I'm looking for that one moment that can create an eternal loop. If it doesn't make me say "wow," I keep searching.

Ethiopia, with its long and rich history, lies at the heart of your work. Your connection to it goes much deeper than a familial bond with one’s birthplace. Could you speak a bit about the special position Ethiopia holds in your life and also in the world imaginary, in terms of being the only nation on the continent of Africa to never be colonized?

I had a very strong connection to my mother during my childhood. She would tell me all the little folk tales, the oral histories. It is a different way of seeing the world. It is even a different way of living in the world! These stories were never written down, and that is how they are. She would say little things that shaped everything.

Ethiopia is a never-colonized country. This is actually one of my artistic starting points with Yatreda. We began by creating characters for a movie about Adwa, about those warriors who sacrificed themselves to keep us independent. That's how Yatreda was born, making a proposal of what these heroes could look like.

The past does inform modern times. The victory against Italian colonization at Adwa in 1896 influenced how we see ourselves. Later, during World War II, Ethiopia continued to stand as a symbol of strength for all African peoples in the world. But what I think is the most important: we must let the past inform our future, not trap us in always saying "in the past, we did this." We need to live it now too.

You know the saying "history is written by the winners"? Right now history is being written and concretized in databases, in AI, by the Western countries. AI is something I support other artists working with, even while Yatreda focuses on handmade work, that's our chosen path, the countryside magic, the oral history I grew up with, it's not included in these systems. And oral history isn't just words on paper and locked there, it has a force that evolves with each telling, and takes a shape which matches the world around it.

This history takes center stage in your work and unfolds sort of episodically, as if each of your series is another chapter in an ongoing and grandiose narrative. Could you walk us through the stories behind your major bodies of work to date, from Adam and Hewan, to Strong Hair, to Abyssinian Queen and Mother of Menelik.

What unites all Yatreda series is each artwork must have something recognizable that speaks across cultures: motherhood, origin stories, identity. But interpreted through the Ethiopian vision, which is how I see the world. Like the musical scale of tizita that makes Ethiopian hearts crumble but moves foreigners too, even without understanding the lyrics.

I was reading that tizita is an Ethiopian idea that relates to memory and longing.

Yes, it’s generally translated as a form of reminiscence, and in music tizita refers to a scale or type of song that embodies feelings of loss and nostalgia. I want our work to be a universal language like this musical tradition.

Our series Adam and Hewan refers to the creation story of Adam and Eve, Hewan being the Ethiopian name for Eve. Here, I wanted to focus on the idea of human temptation. Even when given paradise, humans chose wrong. Many people understand this feeling of having everything, and then losing it.

My series Strong Hair came from a desire to explore identity. From hundreds of subjects, we selected one hundred portraits, each revealing hair as a vessel of culture that expresses identity and marks the various phases of life. To capture these images, we built a 360-degree rig by hand, each person spinning on the same platform, but representing their own story.

In Queen of Sheba, Mother of Menelik, the narrative centers on a legend that connects Ethiopia to Solomon of Ancient Israel, but the art is really about motherhood itself, about forging connections between different peoples.

Each series is another link in what I really view as an unbroken chain, not frozen history but living memory, from our mothers, through us, to our children. That's the Yatreda spirit.

There is an interesting conceptual dialogue between your work and that of other contemporary artists who employ the trope of history. I think for instance of Eleanor Antin, who has examined myths and events such as the last days of Pompeii, or of Samuel Fosso, the Cameroonian-born Nigerian photographer who has pictured himself as Angela Davis, Kwame Nkrumah, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and other prominent figures from the past. Are there certain artists, writers or filmmakers with whom you feel a bond or who have been foundational to your thinking and development?

My mind always goes to the legendary Ethiopian filmmaker Haile Gerima. He is someone who makes history not feel far away, but shows how it speaks to us in life now. What I admire is his dedication. Similar to us, he works very independently.

When I was growing up, Haile Gerima was one of the few Ethiopians who made it internationally. He doesn't chase trends. He’ll dedicate decades to a single topic. When you watch his films, you understand not just how something happened, but how it could happen again. That's powerful.

I also deeply admire the Kenyan artists Kevo Abbra and his partner Sylvia Owalla. I was so lucky to work with them on both Andromeda of Aethiopia and Adam and Hewan. Kevo brings this incredible fusion of traditional African aesthetics with contemporary vision. When he designed the metal wings for our angel or worked with natural materials for the serpent, he understood immediately that we wanted everything handmade, nothing digital. Sylvia, who played Hewan, brought such natural grace. Her timeless beauty.

That's what I learned from watching these artists. History is not dead, it's a living force we channel through our tools.

That concept of history as a living force lies at the heart of your collaboration with LACMA’s archive, which I am excited to explore with you in our next conversation!