For Pablo Picasso, la corrida (or bullfight) was a lifelong passion, from his childhood in Málaga to his late years in the South of France. The subject—with its bullfighters, bulls, and horses—pervades his work in all media through every stage of his career. The theme was especially important in his graphic work, from his very first print of 1899 (depicting a picador holding a lance) to his linocuts of the 1950–1960s.

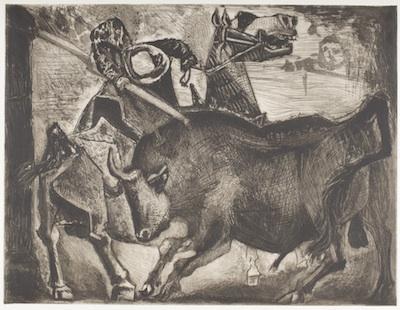

Pablo Picasso, Bull and Picador, 1952, gift of the 2014 Collectors Committee, © 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso, Bull and Picador, 1952, gift of the 2014 Collectors Committee, © 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In Bull and Picador, acquired through this year’s Collectors Committee, Picasso depicts the dramatic moment when the picador stabs the mound of muscle on the bull’s neck, thereby weakening the bull and enabling the matador to execute the fatal thrust later in the performance. It is, in essence, the beginning of the end for the bull. At the same instant, however, the bull gores the horse’s side—a moment of intense primal satisfaction for the bull for which he will ultimately pay with his life. The horse rears up in agony, his angular, rawboned body no match for the massive and swelling musculature of the bull whose body dominates the composition. The scene itself is tightly cropped and foregrounded to enhance the intensity of the action. The vigorous line work and scraping combined with broad applications of aquatint convey the dynamism of the scene. Central to the action and yet completely anonymous is the picador, shielded under his or her castoreño—the traditional wide-brimmed hat. Leaning dramatically forward in full thrust, head down (like the bull), the picador’s hat is viewed as if from above creating a flattening effect that, together with the patterned sleeves of the picador’s jacket, render the bullfighter’s body formless, almost fanciful—a perfect visual foil to the structural articulation of the bull and horse. Indeed the only human face in the whole composition is the spectator in the upper right, lightly defined in aquatint, whose engaged expression perhaps reflects our own.

Pablo Picasso, Femme Torero. Dernier Baiser (Woman Torero. Last Kiss), 1934, purchased with funds provided by Dr. Richard E. Brandes, © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso, Femme Torero. Dernier Baiser (Woman Torero. Last Kiss), 1934, purchased with funds provided by Dr. Richard E. Brandes, © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Bull and Picador joins other Picasso prints related to the bullfight already in LACMA’S collection, allowing the museum to illustrate the artist’s treatment of the subject in varying styles and printmaking techniques. The 1934 line etching Woman Torero. The Last Kiss depicts a female torero slung across the bull’s neck about to receive a “kiss” from the bull, leading to interpretations of the scene as a depiction of Picasso and then-lover Marie-Thérèse Walter.

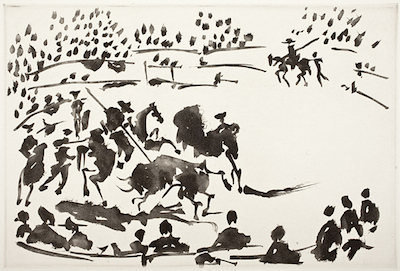

Pablo Picasso, El Picador obligando al toro con su pica (The Picador forcing the bull with his lance) from La Tauromaquia, 1959, gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Gensburg

Pablo Picasso, El Picador obligando al toro con su pica (The Picador forcing the bull with his lance) from La Tauromaquia, 1959, gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Gensburg

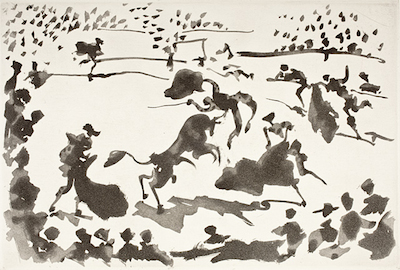

Pablo Picasso, La Cogida (The Goring) from La Tauromaquia, 1959, gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Gensburg, © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso, La Cogida (The Goring) from La Tauromaquia, 1959, gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Gensburg, © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

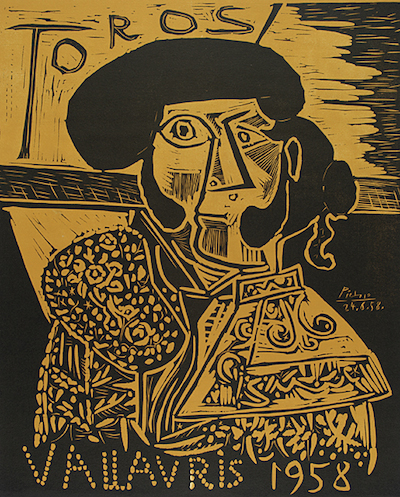

La Tauromaquia from 1959 is a suite of 26 aquatints created as illustrations to the 18th-century bullfighting manual written by renowned Spanish matador Pepe Illo. The fluidity of aquatint allows for loose, notational gestures that capture the movements of the bullfight, while the flat areas of color in linocut suggests solidity and boldness in depicting a matador for the 1958 print celebrating the bullfights at Vallauris in the south of France.

Pablo Picasso, Toros Vallauris 1958, 1958, gift of Lucille and George N. Epstein, © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso, Toros Vallauris 1958, 1958, gift of Lucille and George N. Epstein, © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Bull and Picador demonstrates Picasso’s mastery of intaglio printmaking in his use of aquatint, drypoint, and engraving to build up and animate the composition. It was printed by Roger Lacourière, a master printer that Picasso met in 1934 and who at once encouraged and challenged the artist to experiment using traditional methods in unorthodox ways. In his shop, Picasso produced many of his most technically complex and accomplished prints. Bull and Picador is the sixth and most fully articulated of 20 total states and was never editioned. Unlike Picasso’s editioned intaglio prints that were often steel faced, a process that deadens the vibrancy of a print, this sheet prints with deep blacks and rich surface texture and possesses the immediacy of a drawing. A major achievement within Picasso’s graphic oeuvre and a work of utmost rarity, Bull and Picador now stands at the center of LACMA’s holdings of the artist’s prints.