We often hear the question, “Why are there not more female artists in the show?” It is a reasonable and pertinent question, however, one that is not so easy to answer. While there were many highly talented female artists over the centuries, it is true that many—save for a few exceptions—were in the shadow of men. This had to do primarily with social conditions and the fact that women were often not allowed to study art in public institutions or to travel all by themselves.

Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky, on view in its final week at LACMA, features the work of three female artists who played a crucial role in the birth and evolution of Expressionism in the early 20th century.

Installation view of Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (June 8–September 14, 2014), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA. Middle Left: Paula Modersohn-Becker, Girl with Flower Vases (Mädchen mit Blumenvasen), c. 1907, Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal, photo Credit: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907) was an important precursor of Expressionism. Her career was short, but rich in artistic encounters, which helped to forge her unique style characterized by simplicity of form and an intense tonality. She worked in the artists’ colony of Worpswede in northern Germany and was married to painter Otto Modersohn. She first travelled to Paris in 1900, followed by several other stays in the next years, the last one in 1907, just a few months before her death. In Paris, she studied at the Académie Colarossi and the École des Beaux-Arts. She remained relatively unknown during her life, but this changed dramatically with her premature death at age 31. Soon after, her paintings were shown in museums and galleries all over Germany, and a major retrospective was organized.

It was the work of Post-Impressionist artists—in particular that of Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin, which Modersohn-Becker saw at exhibitions at the Galerie Vollard and at the Salons—that made the deepest impression on her. Modersohn-Becker was also interested in the Nabis’s Symbolist use of color and the “primitive” style of Henri Rousseau, and while in Paris she visited private collector Gustave Fayet to see his Gauguin collection. Her painting Girl with Flower Vases illustrates how she responded to these sources, combining them in a simple, sophisticated, yet powerful image that uses bold contours to delimitate the large planes of color, abandoning traditional linear perspective and going toward flatness, while also giving a highly original interpretation of the female nude.

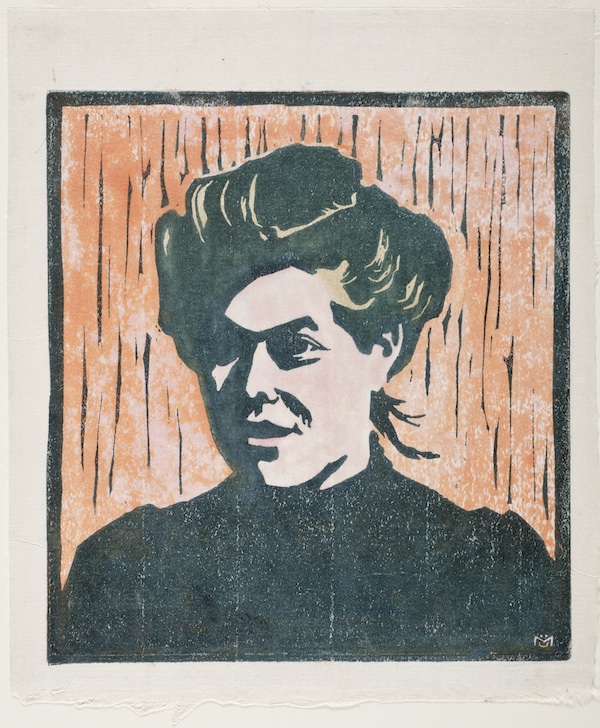

Gabriele Münter, Aurelie, 1906, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, © 2013 Gabriele Münter/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/ LACMA

The two other female artists in the show had longer careers and were both active in Munich, one of the artistic centers in Germany. Gabriele Münter (1877–1962) might be one of the best-known female Expressionist artists today. Although she is often mentioned in the same breath as Wassily Kandinsky, whose companion she was for over a decade, she had a highly impressive career on her own and took part in some of the major avant-garde groups in Germany prior to World War I. After some initial art training and a sojourn of two years in the United States, Münter joined the Phalanx school in Munich, where she became a student of Kandinsky. Between 1906 and 1907, Münter spent several months in Sèvres, France, with Kandinsky; during that time she sojourned in Paris on her own and visited exhibitions and took drawing classes. In Paris, Münter concentrated on the colored-woodcut technique, as illustrated in her print Aurelie. She also started to present work at exhibitions in Paris and had a solo exhibition in Cologne shortly after returning from France.

Installation view of Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (June 8–September 14, 2014), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA. Far Right: Gabriele Münter, Aurelie, 1906, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, © 2013 Gabriele Münter/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo © 2013 Museum Associates/ LACMA

In 1908, Münter and Kandinsky discovered the alpine village of Murnau and, together with fellow artists Alexei Jawlensky and Marianne Werefkin, they started to spend their summers there. This was a turning point for the group, and Münter found to a unique colorfulness and simplicity in her style. She also became interested in folk art, often using traditional objects as motifs. The canvas Wooden Doll demonstrates how Münter incorporated Fauvist and Post-Impressionist tendencies, which she absorbed during her stay in Paris, into a highly original approach to still-life painting. Münter here abandoned traditional perspective for a flattened surface composed by large zones of primary colors, juxtaposing a traditional wooden doll with household objects and fruits. A few years later, she organized, together with Kandinsky, the first Blaue Reiter exhibition in 1911, where she presented her work alongside his and other German and international avant-garde artists.

Marianne Werefkin, Corpus Christi, 1911, Museo comunale d'arte moderne, photo © Museo Comunale d’Arte Moderna

The third female artist featured in the exhibition is Marianne Werefkin (1860–1938), who received her initial artistic training in her native Russia and quickly became famous; she was even regarded as the “Russian Rembrandt.” Werefkin met fellow Russian artist Alexei Jawlensky and came with him to Germany in 1896, settling in Munich. There, she started to host a famous salon, where many avant-garde painters, writers, musicians, and art historians gathered to discuss new artistic theories. Werefkin became one of the founding members of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (New Artists Association of Munich, or NKVM) and was closely associated with the Blaue Reiter group, founded by Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and Münter. Her color palette had been influenced by her summers in the Bavarian alpine village of Murnau, where she worked alongside Jawlensky, Kandinsky, and Münter. She had also become interested in the highly symbolist use of color, which she saw on her frequent visits to France with Jawlensky, by both the Nabis artist group and Paul Gauguin. In her painting Corpus Christi, Werefkin gives a highly spiritual character to the landscape through intensely contrasting colors rendered in vivacious brushstrokes.

Installation view of Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (June 8–September 14, 2014), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA. Right: Marianne Werefkin, Corpus Christi, 1911, Museo comunale d'arte moderne, photo © Museo Comunale d’Arte Moderna

You have until September 14 to see the work of these three remarkable artists in Expressionism in Germany and France. And to discover even more female artists in the permanent collection, visit the installation The Written Image, which features a lithograph by Käthe Kollwitz, who was one of the most important avant-garde artists in early 20th-century Germany and was active as a printmaker and sculptor.