A few years ago, I was skimming through the our department’s well-worn photocopy of the catalogue for California Design 6, the 1960 installment in the Pasadena Art Museum’s influential exhibition series. While I was looking for references to the series’s regulars—landmark local companies and leading craftspeople—I was surprised to come across a listing for Noah Purifoy. I knew of Purifoy as a radical assemblage artist, but the piece described in the catalogue sounded startlingly domestic—a hi-fi cabinet. Visitors to Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada may experience the same moment of curiosity—while most of the objects inthe exhibition are sculptures assembled from everyday objects, the earliest piece (also the artist’s oldest surviving work) is a headboard constructed from sculptural elements.

A man of many overlapping callings—artist, activist, social worker—Purifoy also spent over a decade as a designer, developing stylish interiors, window displays, and furniture. He was one of several major African American artists to begin their careers in the design field of the ’50s and ’60s—Betye Saar collaborated with enamellist Curtis Tann on a small giftwares venture, and John Outterbridge and Dale Brockman Davis both worked for ceramist Tony Hill. With few galleries open to black artists, design—though hardly equitable—provided another path to creative employment. (In 1967 Davis and his brother Alonso directly challenged this injustice by opening Brockman Gallery, which showed work by Purifoy, Outterbridge, Saar, and other artistic luminaries.)

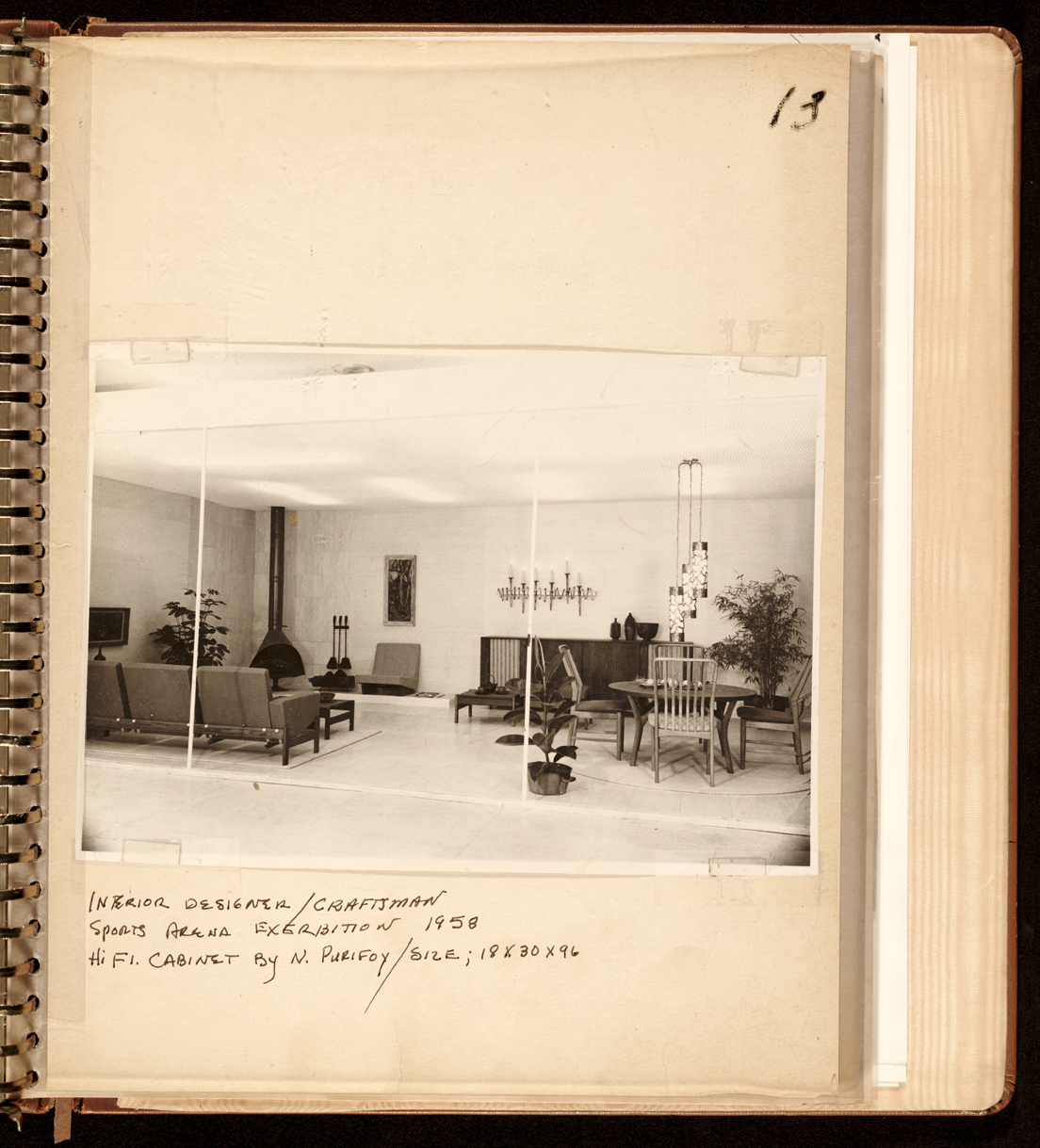

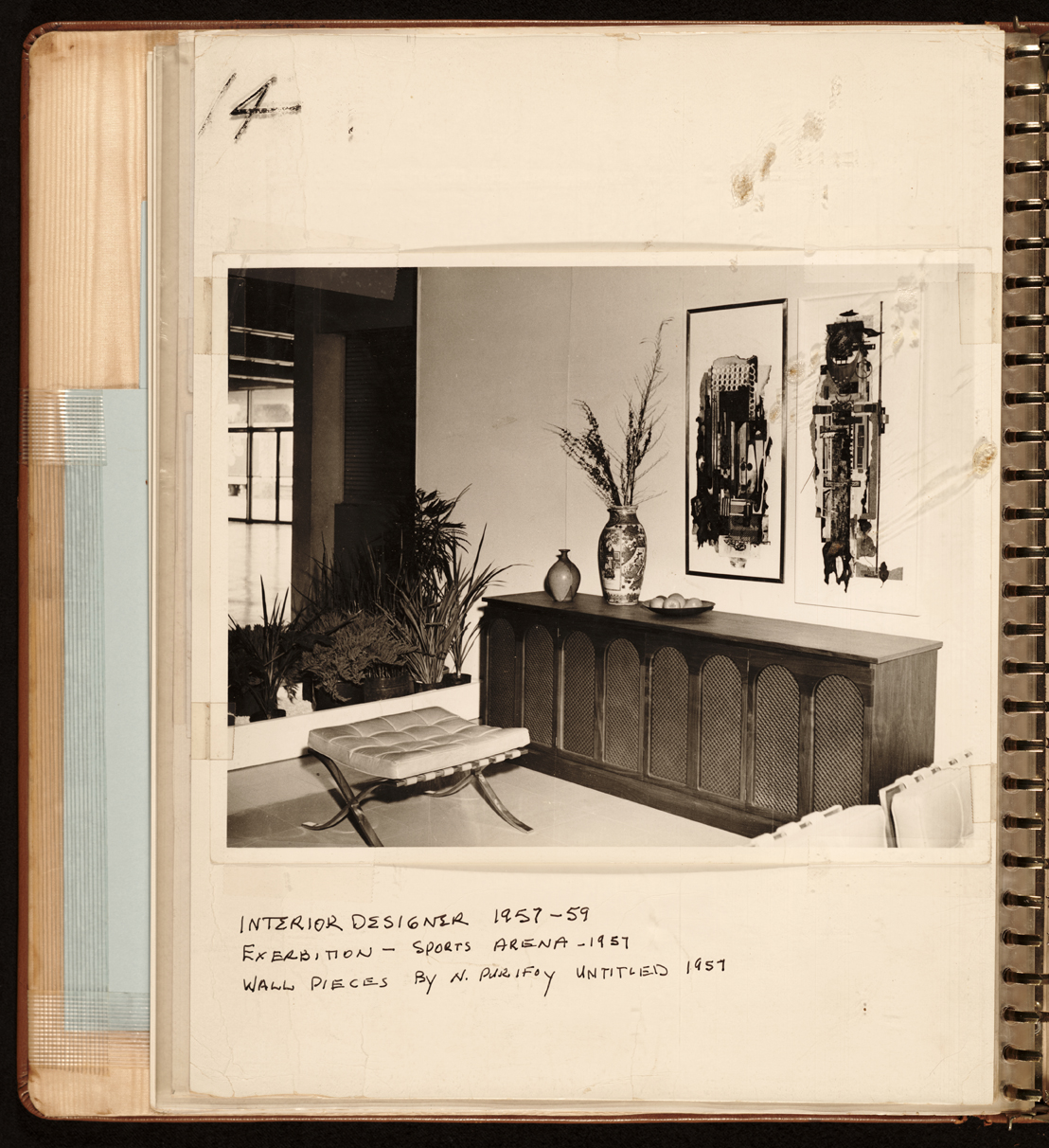

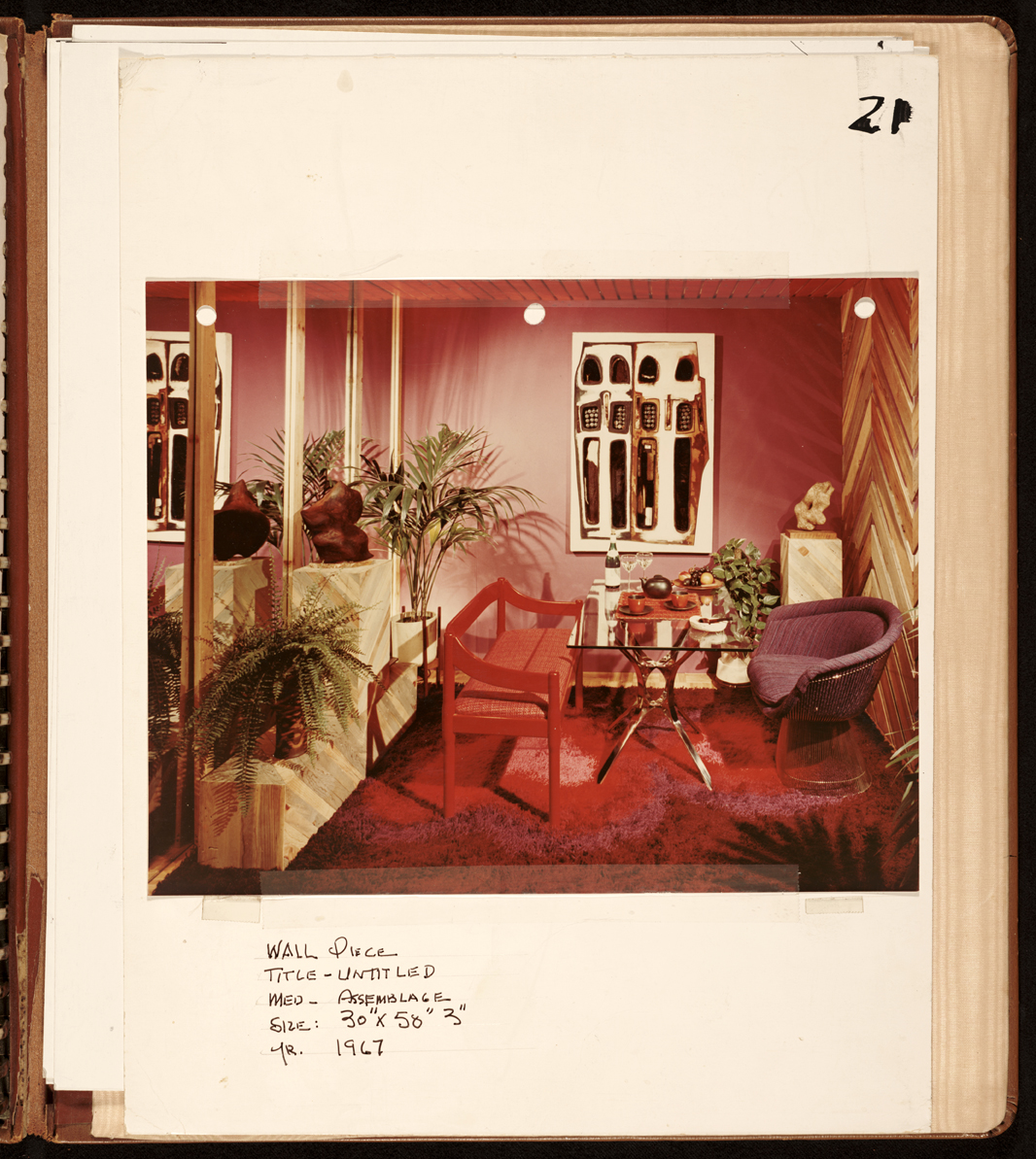

Design initially appealed to Purifoy, who partnered with John H. Smith in the late 1950s, hanging drapery and laying carpets for his more established colleague. The first African American admitted to the National Society of Interior Designers, Smith (who later referred to himself as the “Jackie Robinson of the interior design profession”) earned prominent commissions such as John Lautner’s Malin House (better known as the Chemosphere) and later, in 1975, the Compton City Hall. Purifoy found some initial success as a designer—in addition to the prestigious showing in California Design 6, his scrapbooks also reveal his hi-fi cabinet and wall piece elegantly installed in a trade show interior (though labeled “Sports Arena Exhibition,” these may refer to the Los Angeles Home Show, which moved to the newly built arena in 1959)—but soon chafed against the constraints of clients’ demands. Unable to endure a lifetime of trying to “please Mrs. Jones,” he embarked on a more autonomous artistic path.

In 1966, he again arranged a display at a major interiors trade show—but the installation, 66 Signs of Neon (co-organized with Judson Powell), stood in defiance to the consumerist fantasy of the exposition. Forged from the charred debris and glistening melted neon left after the Watts Rebellion, the series of collaborative sculptures proclaimed the existence of an alternative material reality, staking a place for creativity among ruin. The California of California Design 6—where Purifoy had shown his work only six years earlier—had presented an illusion of endless bounty and opportunity. In contrast, 66 Signs of Neon reflected a community frustrated by decades of deprivation and limitations. While his days as a designer may have been behind him, Purifoy remained acutely aware of the power and symbolism of everyday objects.